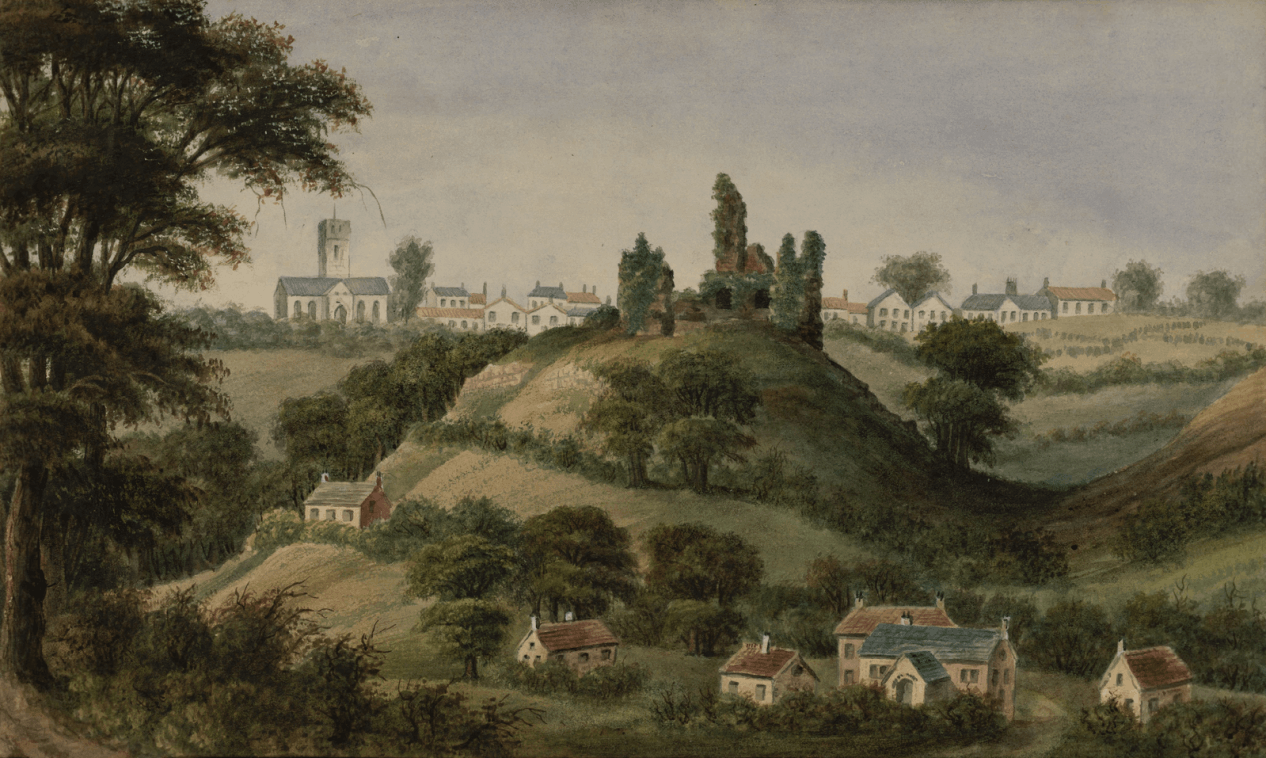

Narberth Castle (1830 – 1869.) Now considered a Norman edifice.

Alphonse Dousseau, CC0

The Hanseatic League - who were they really?

The Grail, The Cataclysm,The Wasteland

& Our Lost Ancient Sovereignty

As another addition to The Dark Earth Chronicles series, we continue “sifting the detritus” of Celtic mythology that we began in the previous one - ‘The ‘History Revolution’ of the early 20th century’. From the perspective of the 10th century cataclysm, we will be looking for clues as to the nature of what came before it and what the cause of it might have been. This may give us a new frame of reference within which to assess what came after and its true effect upon the civilisation we have inherited. However, anyone expecting a discussion of seismology, volcanology, astronomical phenomena or meteorology will be sadly disappointed.

● Introduction

● The Wasteland in Mythology

○ The Adventure in the Otherworld of Art mac Cuinn

○ Rhiannon ○ The Fisher King

● Casting the Net Wider ○ Khazar Island…

● The Symbols of the Grail Quest

○ Cauldrons and other receptacles

○ The Cauldron of The Dagda

○ The Cauldron of Manannan Mac Lir

○ The Cauldron of Dyrnwch the Giant

○ The Cauldron of Life

○ The Cauldron of Bran the Blessed

● The Fishy King

● Christian or Pagan?

● The Fish and Fisherman Symbolism

● The Purpose of the King

● The Origin of the Grail Legend

○ Beau Geste

● Conclusion

Curiously enough, the motif of a wasteland is a common feature in what’s called Celtic mythology. It’s found in the Welsh Mabinogi, Irish Mythology and the later French Grail romances.

Before we dive into this, it’s very important to recognise the fundamental redefinition of all mythology that was undertaken by the Abrahamic religions, particularly Christianity, with regard to the so-called ‘Celtic’ material. The process was known as Euhemerism and was the main weapon used by Christianity, science and early humanists against paganism. It is effectively an early form of Bayesian statistical modelling, whereby the basic tenet – that all mythology originated from real historical events or personages – is set in concrete and everything is redefined in order to conform to that principle. Furthermore, apotheosis – the deification of saints, who were all redefined pagan deities, was an intrinsic part of this process, but it was given the more acceptable name of ‘canonization’ to cover the hypocrisy. Today, this euhemeristic view has become the default of the vast majority of the world’s population.

As a result of this much of the meaning and significance of ancient mythology has been lost. The Welsh Mabinogi has been affected to a severe degree and much of it reads as obscure nonsense because it has all been redefined and placed outside of its original context.

At this point It’s also worth repeating what was discovered in the previous article regarding the pre-Christian Pagan identity of St Bride, Brid, Brigid or Bryth:

“There’s something staring us right in the face here. When people get married in the United Kingdom in an English ceremony, the ritual involves the exchanging of vows between a Bride and a Bridegroom. Often there are also Bridesmaids present. If you look up the modern ‘official‘ etymology of the words Bride, Bridegroom and Bridesmaid they will give you what can best be described as a load of old twaddle…

“...What’s going on here is a microcosm of the Sacred Marriage, or Hieros Gamos, whereby the Bride represents the Mother or Earth Goddess and the Bridegroom her consort. The Bridesmaids are the attendants of the goddess. Bride, or Brigid etc., is one name of the goddess, probably a later one, but there have been others. A Groom is traditionally a male who looks after a horse or horses, who would lead or guide a horse using a Bridle (anciently Bridel) that fits over the horse’s head. This could have easily referred originally to some form of decorative garland or headdress. The concept of a Bridegroom and a Bridle points towards Epona / Rhiannon / Macha, the goddess who, from the earliest of times, took the form of a horse. This is discussed in the article The Horse, Silent Witness to the Past.” Source

According to the Irish tale ‘Adventure in the Otherworld, of Art mac Cuinn’, Conn, the High King of Ireland, married the highly unsuitable Bé Chuma, who had been banished to the human world for adultery. She promptly fell in love with the king’s son, Art mac Cuinn. As a result, his realm turned into a wasteland. He embarked upon an epic voyage searching for a way to lift the curse and eventually found himself as a guest of Manannán mac Lir’s

niece in her Otherworld island residence. When he returned home he found that Bé Chuma had been banished and the curse lifted.

This is curious, because generally in the molested Welsh Mabinogi the Otherworld is always referred to as Annwn, or Annwfn and described as being an actual physical location within our world. The Irish tale in it’s most basic form features a King who commits a discretion that causes his kingdom to become a wasteland. In order to lift the spell or curse, a ‘quest’ has to be undertaken which involved a trip to the Otherworld. This theme is important and we will come across it many times as we continue “sifting the detritus.”

Narberth Castle (1830 – 1869.) Now considered a Norman edifice.

Alphonse Dousseau, CC0

There is also a tale from the Third Branch of The Mabinogi which involves Pryderi, Lord of Dyfed (Pembrokeshire) in Wales, his wife Cigfa, his mother the goddess Rhiannon and Manawydan the brother of Brân the Blessed who was the King of Britain. In this tale they ascend a sacred hill known as Gorsedd Arberth, the Throne, Seat or Mound of Arberth (Narberth,) located in southwestern Wales. In the First Branch of the Mabinogi it is said that, “it is a peculiarity of the mound that whatever high-born man might sit upon it, he will not go away without one of two things: either wounds or blows, or his witnessing a marvel.” When they descended they found that the land of Dyfed had turned into a barren wasteland with no inhabitants. Some years and adventures later Pryderi and his gang returned to Dyfed. Whilst on a hunting expedition Pryderi is drawn into a mysterious fort, or castle, where he finds a beautiful golden bowl. Upon touching the bowl, his feet stick to the floor, his hands stick to the bowl and he loses the power of speech. Manawydan, who had refused to enter the fort, eventually gives up waiting for him and returns to Rhiannon, his wife, to give her the bad news. Their rescue attempt results in Rhiannon suffering the same fate as her son Pryderi while Manawydan then watched as the fort disappeared in a blanket of mist with Pryderi and his nearest and dearest still trapped inside.

Some considerable time later, Manawydan managed to free them from their imprisonment in a curious incident that involved the enchanter Llwyd ap Cil Coed in disguise as a scholar, a priest and a bishop (but not at the same time) which is the ‘smoking gun’ of Christian manipulation. Anyway, it was the capture of Llwyd’s pregnant wife, disguised as a mouse, that persuaded the enchanter (whilst he was pretending to be a bishop,) to lift the enchantment over Dyfed. It turns out that the desolation of the land and the abductions of Pryderi and Rhiannon, were both enchantments performed by this Llwyd, who’s motive was revenge for the humiliation of his friend Gwawl ap Clud, which happened right back in the First Branch of the Mabinogi, at the hands of Pryderi’s father Pwyll and his mother Rhiannon.

This story does sound more than a bit mad. I’m sure, given the time, it would be possible to deconstruct this tale and unravel the Christian interference and redefinition, but I don’t have that time unfortunately.

Pwyll’s vision of Rhiannon seen from the top of Gorsedd Arberth.

Source

If we try to reduce the tale to its basic components it’s first necessary to go back to the source of the ‘revenge’ issue where we find Rhiannon, a mother goddess figure (closely associated with Epona, the ancient British goddess,) appearing in a vision riding a white horse, to Pwyll, the Lord of Dyfed and Head of Annwn (the Otherworld,) whilst he is on the top of Gorsedd Arberth. As Rhiannon is closely associated with Sovereignty it would appear that the earlier episode at the root of the later tale concerned the goddess selecting her consort and granting him sovereignty over the land through sacred marriage. So we have Rhiannon as the Bride and Pwyll as the Bridegroom. The ritual didn’t go ahead as planned for some reason, which in the redefined tale is declared to be trickery by a rival suitor to whom Rhiannon’s father had previously promised her hand in marriage. The redefinition has taken all of the divine status away from Rhiannon and instead placed Pwyll and her father as being capable of defying the goddess and giving her to another, which is ludicrous, but very Christian. The only way that the sacred marriage could have been aborted and Rhiannon betrothed to another is through some form of supernatural intervention. The redefined tale also wants us to believe that the situation was resolved in exactly the same manner except this time Pwyll was the trickster at Rhiannon’s subsequent forced sacred marriage, which again takes all status away from the goddess.

Whatever really took place, it obviously set the precedent of rivalry and revenge that ran through the later Wasteland tale involving Pryderi, described above, and in fact throughout the entire Mabinogi. By the end, the rival faction is embodied in a character described as a ‘magician’ and known as Gwydion, which weirdly was Merlin’s original name before he was ‘reborn’.

Camp Hill Field, Narberth

Believed to be the original site of Gorsedd Arberth

Source

As well as a Bride and Bridegroom, we also get six Bride’s maids after the birth of Pryderi, the son of Rhiannon and Pwyll. They are given the incongruous role of accusing Rhiannon of infanticide and cannibalism following the mysterious disappearance of the new born Pryderi (which means ‘Worry’.) It’s clear that the tales we now know as ‘The Mabinogion’ are a travesty.

The most significant appearance of The Wasteland ‘motif’ is within the Grail literature of the Arthurian Cycle, specifically the tales involving The Fisher King. As we discussed in our article A Quest for the Lost Realm of Faërie...

“The Matter of Britain is largely taken up with the Arthurian cycle. Sounds like a ‘Tour de Britain’ bicycle race. This in turn is split into the Vulgate and Post-Vulgate cycles. To make matters more confusing, these cyles overlap, but generally cover the period from the 12th century to the 14th. Basically, The Matter of Britain began when the bloody monks, friars, scribes and bishops interfered with the legends, but it also includes some later anonymous sources. The Vulgate cycle is when some Norman / French poets interfered with them and the Post-Vulgate cycle is when Norman / French and German poets twisted Arthur and his Knights into Christian heroes of the Holy Grail and the quasi-mystical Rosicrucian movement.”

Anyway, the thing is there are so many different versions of the same tale that it makes any investigation of The Wasteland element quite tedious and confusing. Fortunately better people than I have already spent a great deal of their lifetimes studying the very same thing. One such person was Jessie L Weston who wrote ‘From Ritual to Romance’ in 1919 – the same year that Harold Bayley published his book (featured heavily in The History Revolution of the Early 20th Century), which is quite a coincidence… although hers wasn’t published until the following year.

Perceval arrives at the Grail Castle, to be greeted by the Fisher King.

Artist unknown., Public domain

In case you’re not familiar with the story, briefly and very basically, the Fisher King is the current guardian of the Grail. However, he is now infirm and old, his kingdom has turned to a Wasteland. King Arthur and his knights have been on a quest for the Grail and one of them eventually arrives at the castle of the Fisher King. The knight or knights are required to perform various tasks in order to heal the Fisher King, thus restoring the Wasteland and obtaining the Grail.

The various versions all contain strong elements of ‘holification’ and they are all totally redefined, Christianised interpretations of what must have been a much older tradition. In many ways we see the same basic ingredients as in the Irish tale of Art mac Cuinn, even down to the ‘golden bowl’ in the castle. Some of the Christianised versions incorporate other Christian legends. The Grail itself is completely redefined as a physical object – ‘The Holy Grail’ – and firmly associated with Christ. However, curiously the Holy Grail doesn’t feature anywhere in Christian rituals or dogma (even the Eucharist vessel is not a representation of the Grail as we will see later.) One highly significant point is that at no time in any of the different versions is any mention made of the Fisher King’s Queen, it’s all about The Fisher King and his land.

Different versions assign a different knight as the quester and even those featuring the same one emphasise or change different aspects of the story or even add new ones. I don’t want to spend a huge amount of time showing all of the various details within the different versions of the Grail Quest, but I can assure readers that Jessie L Weston has already done a magnificent job of that and so I will highlight the relevant parts of her analysis whereby she summarised the different versions of the Grail Quest as follows:

“(a) There is a general consensus of evidence to the effect that the main object of the Quest is the restoration to health and vigour of a King suffering from infirmity caused by wounds, sickness, or old age;

“(b) and whose infirmity, for some mysterious and unexplained reason, reacts disastrously upon his kingdom, either depriving it of vegetation, or exposing it to the ravages of war.

“(c) In two cases it is definitely stated that the King will be restored to youthful vigour and beauty.

“(d) In both cases where we find Gawain as the hero of the story, and in one connected with Perceval, the misfortune which has fallen upon the country is that of a prolonged drought, which has destroyed vegetation, and left the land Waste; the effect of the hero's question is to restore the waters to their channel, and render the land once more fertile.

“(e) In three cases the misfortunes and wasting of the land are the result of war, and directly caused by the hero's failure to ask the question [WS: “What is the Nature of the Grail?”] we are not dealing with an antecedent condition. This, in my opinion, constitutes a marked difference between the two groups, which has not hitherto received the attention it deserves. One aim of our present investigation will be to determine which of these two forms should be considered the elder.

“But this much seems certain, the aim of the Grail Quest is two-fold; it is to benefit (a) the King, (b) the land. The first of these two is the more important, as it is the infirmity of the King which entails misfortune on his land, the condition of the one reacts, for good or ill, upon the other; how, or why, we are left to discover for ourselves.”

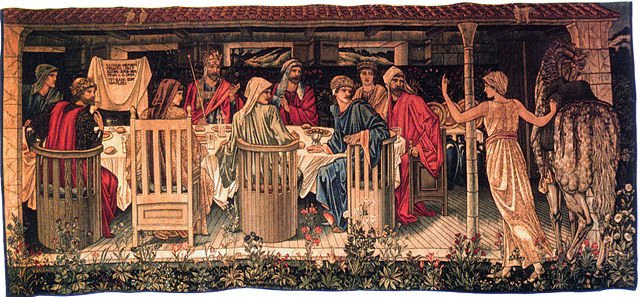

The Knights of the Round Table are Summoned to the Quest by the Strange Damsel. Tapestry by Morris & Co. 1891-94

(Sir Edward Burne-Jones, overall design and figures; William Morris, overall design and execution;

John Henry Dearle, flowers and decorative details., Public domain)

The later adaptations introduce a significant change to the narrative. Before the arrival of the knight, neither the King nor the land are in an unhealthy state. However, simply because the knight doesn’t ask the appropriate question about the nature of the Grail, the King becomes ill and his kingdom a Wasteland. In fact he never completes his quest and simply buggers off to seek more knightly adventures making the whole Quest for the Holy Grail thing a total nonsense.

Another later version, preserved in the ‘Sone de Nansai’, we find the introduction of a completely new theme. Joseph of Arimathea, apparently the patron Saint of Norway, is the Fisher King who guards the Grail and the Lance in a monastery on an island in the interior of Norway. There’s weird genealogy that relates Joseph to other members of Arthur’s Round Table. He has become infatuated with the daughter of the Pagan King of Norway, whose father he has killed. In spite of being baptised she is still a Pagan at heart, but he marries her anyway. This angers God who punishes him for his sins. He turns the island into a Wasteland and curses Joseph’s lineage. Then there was the 1991 movie ‘The Fisher King’ which was another insult to the original.

When we get to the final incarnation of the Grail Quest story the questing knight has become Sir Galahad. There is no Wasteland and there are now the additional characters of the Fisher King’s father and ‘The Old King’. These two get healed, the latter, who has been kept alive for centuries, gets better simply by Galahad’s presence as the fulfilment of a prophecy. The advantages derived from the success of the Quest in this version are all personal and spiritual with no reference to sovereignty or the land whatsoever..

“To sum up the result of the analysis, I hold that we have solid grounds for the belief that the story postulates a close connection between the vitality of a certain King, and the prosperity of his kingdom; the forces of the ruler being weakened or destroyed, by wound, sickness, old age, or death, the land becomes Waste, and the task of the hero is that of restoration.”

(Please note: Any quotes without a Source are from Jessie L Weston.)

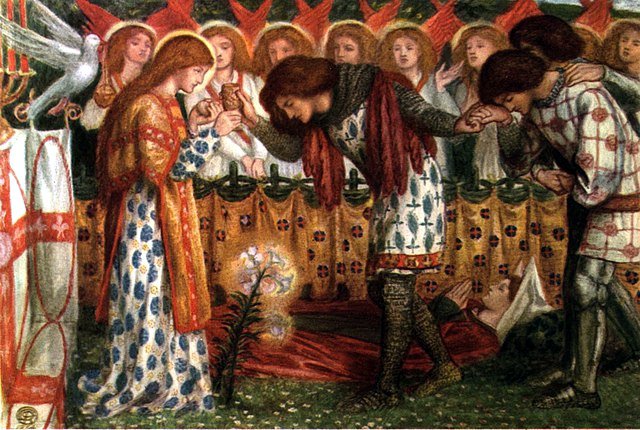

How Sir Galahad, Sir Bors and Sir Percival were Fed with the Sanc Grael;

But Sir Percival's Sister Died by the Way

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1864, Public domain

Jessie L. Weston examined other traditions from diverse cultures to see if there was any evidence of a similar relationship between the welfare of the King and the welfare of the kingdom.

In this regard she discovered obscure, fragmentary cuneiform texts from the Sumerian-Babylonian pantheon connected with prayers and invocations addressed to the deity known as Tammuz. They are all 'Lamentations,' or 'Wailings,' “having for their exciting cause the disappearance of Tammuz from this upper earth, and the disastrous effects produced upon animal and vegetable life by his absence,” in other words his absence caused a Wasteland. His return could only be effected by the intervention of a goddess, the mother, sister, or paramour, of Tammuz, who would descend into the Otherworld and persuade him to return with her to the earthly realm.

“Then He [God] said to me, ‘Son of man, have you seen what the elders of the house of Israel do in the dark, every man in the room of his idols? For they say, “The Lord does not see us, the Lord has forsaken the land.”’ And He said to me, ‘Turn again, and you will see greater abominations that they are doing.’ So He brought me to the door of the north gate of the Lord’s house; and to my dismay, women were sitting there weeping for Tammuz.” Ezekiel 8:12-14

Source

“It is perfectly clear from the texts which have been deciphered that Tammuz is not to be regarded merely as representing the Spirit of Vegetation; his influence is operative, not only in the vernal processes of Nature, as a Spring god, but in all its reproductive energies, without distinction or limitation, he may be considered as an embodiment of the Life principle, and his cult as a Life Cult.”

Tammuz, like many other pre-Christian Pagan gods and goddesses, was part of the natural annual symbolic death, burial and resurrection cycle.

Similar ritual displays of weeping and mourning are also apparent in the Adonis cult of Western Asia and in Greece. We also find a weeping woman, or several weeping women in the various Grail romances who are never satisfactorily accounted for.

The Castle of Maidens, circa 1890

E A Austin, Public domain

“In the version of the prose Lancelot, Gawain, during the night, sees twelve maidens come to the door of the chamber where the Grail is kept, kneel down, and weep bitterly, in fact behave precisely as did the classical mourners for Adonis, behaviour for which the text, as it now stands, provides no shadow of explanation or excuse.”

In the Diu Crone version of Perceval, the Grail-bearer and her maidens are the only living beings in an abode of the Dead – the Otherworld in Otherwords. In one particular manuscript, a passage has been inserted which states that when the Quest is achieved, the hero shall learn the cause of the maiden's grief, and also the explanation of the Dead Knight upon the bier. However, there are no weeping maidens nor a dead knight on a bier in the Perseval version. They only feature in the Gawain stories. No doubt one of those pesky scribe-monks had been at the communion wine that day. However, this detail should be remembered for later when we discuss the nature of the Grail itself.

“Among certain peoples, the role of the god, his responsibility for providing the requisite rain upon which the fertility of the land, and the life of the folk, depended, was combined with that of the King...

“...This was the case among the Celts; McCulloch, in The Religion of the Celts, discussing the question of the early Irish geasa or taboo, explains the geasa of the Irish kings as designed to promote the welfare of the tribe, the making of rain and sunshine on which their prosperity depended. ‘Their observance made the earth fruitful, produced abundance and prosperity, and kept both the king and his land from misfortune. The Kings were divinities on whom depended fruitfulness and plenty, and who must therefore submit to obey their 'geasa.'”

‘Geasa’ is defined as follows:

“geas (plural geasa or geases)

(originally in ancient Irish religion and mythology) A (generally magical) vow, obligation or injunction placed upon someone to do or not do something, which typically brings harm if violated and blessings if obeyed.” Source

Regardless of any alternative ideas regarding the validity of Ancient Greek chronology, this same idea is apparent in The Odessey, whereby the king was regarded as a representative of Zeus and he was only capable of fulfilling this role if he was perfect, unblemished and without any physical or mental defects…

"'Even as a king without blemish, who ruleth god-fearing over many mighty men, and maintaineth justice, while the black earth beareth wheat and barley, and the trees are laden with fruit, and the flocks bring forth without fail, and the sea yieldeth fish by reason of his good rule, and the folk prosper beneath him.' The king who is without blemish has a flourishing kingdom, the king who is maimed has a kingdom diseased like himself, thus the Spartans were warned by an oracle to beware of a 'lame reign.'" (Od. 19. 109 ff.)

This same tradition was recorded in the third edition of The Golden Bough (1906–1915) as being current within the Shilluk tribe, who inhabited the banks of the White Nile. The economy of this 40,000 strong tribe was, at that time, totally agrarian, based upon flocks and herds, grain and millet. Their king was regarded as the re-incarnation of Nyakang – their semi-divine hero responsible for establishing the tribe in its present land and for providing the rain that enables their pastoral way of life to continue and prosper.

Mound of the Shilluk king at Fashoda with his four huts built on top.

Charles Gabriel Seligman (1873-1940,) Public domain

“The King, though regarded with reverence, must not be allowed to become old or feeble, lest, with the diminishing vigour of the ruler, the cattle should sicken, and fail to bear increase, the crops should rot in the field and men die in ever growing numbers. One of the signs of failing energy is the King's inability to fulfil the desires of his wives, of whom he has a large number. When this occurs the wives report the fact to the chiefs, who condemn the King to death forthwith, communicating the sentence to him by spreading a white cloth over his face and knees during his mid-day slumber.”

Shrine dedicated to Nyikang

Georg Buschan 1914, Public domain

It’s very interesting to note that today the Shilluk are virtually extinct. From 1955 onwards they have been embroiled in the Sudanese civil wars…

“Today, the Shilluk government is a democracy, with an elected headman voted in by a council of hamlet heads… Colonial policies and missionary movements have divided Shilluk into Catholic and Protestant denominations… During the summer of 2010, the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA), in an attempt to disarm the tribe and stop a local Shilluk rebellion, burned several villages and killed an untold number of civilians in South Sudan's Shilluk Kingdom. Over 10,000 people were displaced during the rainy season and sent fleeing into the forest, often naked, without bedding, shelter, or food. Many children died from hunger and cold” Source

I wonder, if Jessie L Weston was still alive today, whether she would consider that the Shilluk’s loss of their King – the re-incarnation of Nyakang – along with their entire religion, culture, land and lives, were related in any way? I’m sure many will consider this as simply coincidence. Personally I see it as a microcosm of the greater macrocosm we call ‘history’.

If you look at the official history of what is now called ‘The Shilluk Kingdom,’ (how can a population of 40,000 be considered a bloody kingdom?) you will find all manner of border conflicts, alliances, invasions, looting, massacres, centralised government, the replacement of the King by an Egyptian governor in 1869, which is all totally at odds with the picture painted in 1905 by Dr James Frazer in The Golden Bough.

Miss Weston had this to say at the time..

“This survival is of extraordinary interest; it presents us with a curiously close parallel to the situation which, on the evidence of the texts, we have postulated as forming the basic idea of the Grail tradition—the position of a people whose prosperity, and the fertility of their land, are closely bound up with the life and virility of their King, who is not a mere man, but a Divine re-incarnation. If he 'falls into languishment,' as does the Fisher King in Perlesvaus, the land and its inhabitants will suffer correspondingly; not only will the country suffer from drought, "Nus pres n'i raverdia," but the men will die in numbers.”

If it was a prophecy, it couldn’t be more accurate.

The same Dr Frazer also wrote of another similar tradition in West Africa. In ‘Folk-Lore (Vol. XXVI)’ we find that…

“the dominant Ju-Ju of Elele, a town in the N.W. of the Degema district, is a Priest-King, elected for a term of seven years. ‘The whole prosperity of the town, especially the fruitfulness of farm, byre, and marriage-bed, was linked with his life. Should he fall sick it entailed famine and grave disaster upon the inhabitants.’ So soon as a successor is appointed the former holder of the dignity is reported to 'die for himself.' Previous to the introduction of ordered government it is admitted that at any time during his seven years' term of office the Priest might be put to death by any man sufficiently strong and resourceful, consequently it is only on the rarest occasions (in fact only one such is recorded) that the Ju-Ju ventures to leave his compound. At the same time the riches derived from the offerings of the people are so considerable that there is never a lack of candidates for the office.”

Felix and I have been sitting on the following information for quite a while now and neither of us is entirely sure where we found it. We think it was from "The Truth About Khazars" by Benjiman Freedman in 1954. Anyway, during the preceding decade to the date of the information, archaeological investigations had uncovered what was claimed to be the last capital of the Khazars. It covered both banks of the lower course of the Volga. The city was in three distinct parts, one on each bank of the river and another in-between on an island in the river. The Khazar Qaghan, or sacred ruler, lived on the island in a building made of brick, which was exclusive to his residence and never used anywhere else. According to one Byzantine source the island was named Atech, although it’s claimed that was an error and it was really ‘Atel’.

The Qaghan had no real power, he was solely a figurehead. Of course, his chief deputy (called an ‘ishad’ – a term of Iranian origin) and his government, had all the real power, just as in modern monarchies. The Qaghan lived under severe restrictions, for example he was only allowed to leave the island on four specific occasions each year and if he stayed away longer than permitted, he was strangled. Upon his death he was buried in a huge complex that included many false tombs. Once he was interred, the river was allowed to overflow the burial complex and drown all those who had built it and buried the Qaghan inside.

The Khazar Islands.

An aborted project comprising 55 artificial islands on the coast of the Caspian Sea.

Source

The system described above is often referred to as a ‘diarchy’, or ‘biarchy’, even a ‘tandemocracy’, but these terms are all misleading because the Qaghan ruled over nothing at all and was treated like a fragile delicate flower who had to be put away in his box for safekeeping after a few minutes. There was no shared rulership involved whatsoever. The source of this information states that the same system used by the Khazars was in operation during the same period…

“...among the Hungarians, Vikings, the Merovingian kings and the Carolingian majordomos, the Kieavan kniazs and their vojevodas, the Abbasid Khalifas and the Suljuk sultans, the Japanese Mikados and Shoguns, etc.”

During our investigation into Iranian National History, which provided the title of ‘ishad’ for the Khazar deputy as we have seen above, there was evidence of a definite separation of responsibilities between the King and his close advisors or ministers. However, it wasn’t so extreme and left the King with determination over wars and other conflicts, whilst the deputies (mainly priests) looked after the commercial, economic and administrative duties.

Jessie L Weston didn’t know about the Khazars or the others mentioned who had a similar system, only the two African examples. If she had then I’m sure she would have been even more convinced than she was when she claimed that...

“there lies a continuous chain of evidence, expressed alike in classical literature, and surviving Folk practice, I would submit that there is no longer any shadow of a doubt that in the Grail King we have a romantic literary version of that strange mysterious figure whose presence hovers in the shadowy background of the history of our Aryan race; the figure of a divine or semi-divine ruler, at once god and king, upon whose life, and unimpaired vitality, the existence of his land and people directly depends.” [PS: The Aryan thing was fashionable at that time.]

The Grail Temple

Source

Accepting this as a fact, she logically concludes that those versions of the Grail Quest that fail to connect the misfortunes of the land directly with the disability of the king and instead blame them on the failure of the Quester to ask an obscure question, are not true portrayals of the original theme...

“The woes of the land are directly dependent upon the sickness, or maiming, of the King, and in no wise caused by the failure of the Quester. The 'Wasting of the land' must be held to have been antecedent to that failure, and the Gawain versions in which we find this condition fulfilled are, therefore, prior in origin to the Perceval, in which the 'Wasting' is brought about by the action of the hero; in some versions, indeed, has altogether disappeared from the story...

“...As a matter of fact I believe that the 'Waste Land' is really the very heart of our problem; a rightful appreciation of its position and significance will place us in possession of the clue which will lead us safely through the most bewildering mazes of the fully developed tale...

“...We have found, further, that this close relation between the ruler and his land, which resulted in the ill of one becoming the calamity of all, is no mere literary invention, proceeding from the fertile imagination of a twelfth century court poet, but a deeply rooted popular belief, of practically immemorial antiquity and inexhaustible vitality; we can trace it back thousands of years before the Christian era, we find it fraught with decisions of life and death to-day.”

A great deal of scholarly effort has been spent upon the meaning, significance and origin of the various symbols displayed in the hall of the Grail castle, namely a cup and / or dish, a stone, a spear or lance and a sword. As Miss Weston makes clear, any theory that attempts to explain these symbols must account for the entire collection rather than simply one object in isolation. For example the Longinus legend, whereby a Roman soldier pierced the side of the crucified Jesus with a lance, doesn’t have anything to do with a cup or dish, a stone and a sword. These objects never appear together in Christian art or tradition. The lance or spear is always associated with the Cross, Nails, Sponge, and the Crown of Thorns, but never with the Chalice of the Mass. Neither does the lance or spear have any role to play in relation to the Grail in its guise as a dish that provides food. Even the later association of the Grail with the cup used by Christ at the Last Supper has no other associations whatsoever.

‘The Damsel of the Sanct Grael’

Dante Gabriel Rossetti 1874. Public Domaim

At this point in the proceedings I find myself disagreeing with Miss Weston. Whilst she acknowledges that all of the symbols are found together within the Treasures of the Tuatha de Danann (which we will discuss momentarily,) she rejects it on the basis that the object corresponding to the Grail is the cauldron of the Dagda, which she finds unable to reconcile with a cup, dish or even a bowl. Instead she goes on to claim that the collective grail symbols have their true meaning in the suits of the tarot…

Most European suits are fairly similar with the exception of the Spanish. They have copas (cups,) the equivalent of hearts, oros (literally "golds" as in gold coins) the equivalent of diamonds, espadas (swords), the equivalent of spades which is nearly the same word, and bastos (meaning “clubs” as in weapons.) So, here the associations are quite mixed up, there’s a match for the cup and hearts and the swords with swords, but there is no Lance association with oros or coins and the Dish is a club or cudgel. However, if you switch them around then conceivably the Lance could be the bastos and the Dish the oros or coins.

Personally, I find those associations much more of a problem than the Tuatha de Danann ones between a bowl, dish or cup with the cauldron of Dagda: a sword with the Sword of Núada; a spear or lance with the Spear of Lug and a stone with the Stone of Fál (the Lia Fáil – used in sacred marriage rituals and still used today in coronation ceremonies… which should really be quite a noticeable clue.)

It must be born in mind that languages change over time and that every new translation of one language into another, or even an older version of the same language into a newer one, will be highly susceptible to errors as well as bias and deliberate manipulation. I suppose Miss Weston could use the same argument regarding the suits of the tarot comparison, but whereas a cauldron is a receptacle as much as is a cup, dish or bowl; a heart bears no resemblance to a cup, chalice or goblet (except in Spain;) a Lance bears no resemblance to a diamond; a dish whilst being a receptacle bears no resemblance to the symbol for clubs. The sword is associated with spades in the Spanish suits. The thing is though, we’re missing the stone symbol entirely in the Tarot analogy.

This is currently on sale as a ‘Celtic Cauldron’ even though it looks just like a dish.

Source

I think it’s also important to recognise that one overwhelming assumption was implicit in the redefinition of the ‘Grail’ into ‘The Holy Grail’. Even the word ‘Grail’ itself is untraceable beyond 13th century old French…

“’Holy Grail’ is Englished from Middle English seint gral (c. 1300), also sangreal, sank-real (c. 1400), which seems to show deformation as if from sang real "royal blood" (that is, the blood of Christ). The object had been inserted into the Celtic Arthurian legends by 12c., perhaps in place of some pagan otherworldly object.” Source

I would say that’s a definite “perhaps.” In ‘Celtic’ culture there are many magical cauldron’s and receptacles.

The cauldron of The Dagda, or Daghda, the father god of the Tuatha de Dannan, was so enchanted that no matter how many people sat down to eat around it, they would all be fed. It’s interesting to note that he also had a mighty club that was so enormous it had to be transported on wheels, and it took ten men to lift it. One end of the club killed the living with one blow, while the other end could revive the dead. So, three symbols there: abundance, death and rebirth. The cauldron was brought to Ireland by the Tuatha de Dannan from the four island cities ‘in the North’; Murias, Falias, Gorias and Findias. The Dagda accompanied them and was also known as the All Father, Eochaid Ollathair (Father of All), and Ruadh Rofessa (The Red One).

Is interesting in that it shows a connection between Irish, Manx, Scottish, Welsh and British traditions. Manannan Mac Lir is a sea deity in Irish mythology and the Isle of Man was even named after him. He is the son of the obscure Lir meaning ‘sea’. He is often portrayed as guiding souls between the earthy realm and the Otherworld. He is usually associated with the Tuatha de Danann, although most scholars consider him to be of an older race of deities. In the Welsh / British tradition he is known as Manawydan fab Llŷr whom we have already met along with Pryderi and Rhiannon in the earlier discussion of the Mabinogi. Manannán and Manawydan were both associated with a “cauldron of regeneration.”

If meat for a coward were put in it to boil, it would never boil; but if meat for a brave man were put in it, it would boil quickly allowing the brave to be distinguished from the cowardly. This could be the same cauldron that appears ion the poem ‘The Spoils of Annwn’ (Preiddeu Annwfn) as it shares the same property whereby it will not boil the food of a coward. The 20th century Arthurian scholar, R.S.Loomis, suggested that this feature might be the distant origin of an incident in the Prose Lancelot, where the Grail serves food to everyone except Gawain, who had been judged unworthy, presumably by the cauldron/grail.

Similar ‘fast-food’ facilities were provided by The Crock and the Dish of Rhygenydd the Cleric which provided any food that was wished for, and The Horn of Brân Galed of the North which did exactly the same but with drink.

Cerridwen

Christopher Williams, 1934.

Public domain

Cerridwen was of the Welsh tradition and a goddess of the Underworld. She was a powerful enchantress associated with knowledge, wisdom and magic, the source of which was her cauldron. In some tales she was also depicted as the mother of Taliesin (Merlin.) In one such version he was the son of a demon and a fairy who, as a young boy, was sent to work in the realm of the Great Goddess (Cerridwen) as a kind of skivvy, serving the Nine Maidens as they were tending the Cauldron of Life. At one point the contents of the cauldron accidentally splashed onto Merlin’s hand and from that point onward he was gifted with the arts of prophecy and sorcery. Other versions are much more fanciful and have since become the nucleus of a great deal of mystical speculation as we shall see in the next article. Anyway, her cauldron is known as both The Cauldron of Knowledge and The Cauldron of Life.

If we return briefly to the poem ‘The Raid on Annwn’ (Preiddeu Annwfn,) where Arthur and his army set off into the Arctic to raid the Otherworld in order to retrieve a cauldron, we find that the Arctic association with the Otherworld goes back a very long way. As well as being considered the cradle and origin of civilisation, it was also seen as a place of returning. Its title of The Land of the Dead is misleading to our modern world-view, but it should be understood as a joyful return to The Otherworld, the source, the Cauldron of Life. This is obviously the origin of the Tuatha de Dannan, but more of that in the next article.

In the Celtic legend of Bran the Blessed, the cauldron appears as a vessel of wisdom and rebirth. Bran, the mighty warrior-god, obtained the magical cauldron from Cerridwen (whilst in disguise as a giantess) who had been ‘expelled’ from a lake in Ireland, which simply means she came and went to the Otherworld via the lake. The cauldron could resurrect the corpse of dead warriors placed inside it (this scene is believed to be depicted on the Gundestrup Cauldron). Bran gave the cauldron to his sister Branwen and her new husband Math — the King of Ireland — as a wedding gift, but when war broke out between the two kings, Bran set out to take the valuable gift back. He was accompanied by a band of a loyal knights (including his brother Manawydan and Pryderi whom we have already met earlier) but only seven returned home… coincidentally exactly the same number who returned from The Raid on Annwn.

Dinas Bran Castle

Alphonse Dousseau, 1830. Public domain

Miss Weston does recognise the value of the ‘Celtic’ symbolism, but she has her own, very Victorian theory…

“On the whole, I am of the opinion that the treasures of the Tuatha de Danann and the symbols of the Grail castle go back to a common original, but that they have developed on different lines; in the process of this development one 'Life' symbol has been exchanged for another. But Lance and Cup (or Vase) were in truth connected together in a symbolic relation long ages before the institution of Christianity, or the birth of Celtic tradition. They are sex symbols of immemorial antiquity and world-wide diffusion, the Lance, or Spear, representing the Male, the Cup, or Vase, the Female, reproductive energy.”

Unfortunately she is going against her own earlier maxim whereby any theory that doesn’t deal with all of the symbols as a group, but only with some in isolation, will not suffice.

“The personality of the King, the nature of the disability under which he is suffering, and the reflex effect exercised upon his folk and his land, correspond, in a most striking manner, to the intimate relation at one time held to exist between the ruler and his land; a relation mainly dependent upon the identification of the King with the Divine principle of Life and Fertility. This relation, as we have seen above, exists to-day among certain African tribes.”

The portrayal of the king in the various different versions of the Grail story is a confusing mess. In some versions he is not wounded or even ill and doesn’t like fishing. At other times it’s a knight, his brother, father or grandfather who is either dead or wounded and in one instance the king himself is one of the ‘undead’. The imposition of the family of Joseph of Arimathea as Christian guardians of the Holy Grail has confused matters even more.

“Sometimes he is in extreme old age, and in certain closely connected versions the two ideas are combined, and we have a wounded Fisher King, and an aged father, or grandfather. But I would draw attention to the significant fact that in no case is the Fisher King a youthful character; that distinction is reserved for his Healer, and successor.”

The evidence presented earlier concerning the Tammuz and Adonis cults when considered alongside the Spring Festivals of European Folklore and the ‘Mumming Plays’ of the British Isles, it’s very clear to see that the main god or spirit of nature is considered to be dead or dying...

"The one point in which there is no variation is that—the character is killed and brought to life again. The play is a ceremonial performance, or rather it is the development in dramatic form of what was originally a religious or magical rite, representing or realizing the revivification of the character slain. This revivification is the one essential and invariable feature of all the Mummer's plays in England."(Source: ‘Masks and the Origin of the Greek Drama’, F. B. Jevons, 1916.)

The purpose of all these rituals and ceremonies is to revive the god or the spirit of nature. This must indicate the origin of the Grail Quest. Therefore, the earliest, most original form of the Grail story should comply to this situation – the incapacity of the ruler whose kingdom has become a wasteland and who must be healed or revived by the younger Quester thereby reviving the land…

“Viewed from this standpoint the Gawain versions (the priority of which is maintainable upon strictly literary grounds, Gawain being the original Arthurian romantic hero) are of extraordinary interest. In the one form we find a Dead Knight, whose fate is distinctly stated to have involved his land in desolation, in the other, an aged man who, while preserving the semblance of life, is in reality dead.”

The Vigil of Gawain

John Pettie, 1884. Public domain

Even in Miss Weston’s time there was a war going on between those who claimed that the Grail Quest was comprised of wholly Christian symbolism and those who recognised it as ‘Celtic’ Folklore. The Christian argument relies upon the title of ‘Fisher King’ and the symbolism of the Eucharist, even though it doesn’t involve a lance, spear, sword, stone or dish. The fish was adopted by early Christianity in the same way as the cross and gave rise to the title 'Fishers of Men' and to the Pope’s ring. However, no Christian explanation is ever offered to account for the condition of the Fisher King being either maimed or dead.

“So far as the present state of our knowledge goes we can affirm with certainty that the Fish is a Life symbol of immemorial antiquity, and that the title of Fisher has, from the earliest ages, been associated with Deities who were held to be specially connected with the origin and preservation of Life.”

The fish figures prominently in Indian cosmogony. Manu, the first man, agrees to protect a small fish (Jhasa) he finds which later saves him from a universal cataclysm. The first Avatar of Vishnu the Creator is a Golden Fish and known as Matsaya. Traditionally a great feast is held on the twelfth day of the first month of the Indian new year in honour of Matsaya, which must be rebirth celebration.

Vishnu’s first avatar, Matsaya

Source

Later, the Fish Avatar was transferred to Buddha and the symbols of the Fish and Fisher are widely used in Buddhism…

“Thus in Buddhist monasteries we find drums and gongs in the shape of a fish, but the true meaning of the symbol, while still regarded as sacred, has been lost, and the explanations, like the explanations of the Grail romances, are often fantastic afterthoughts… In the Mahayana scriptures Buddha is referred to as the Fisherman who draws fish from the ocean of Samsara to the light of Salvation. There are figures and pictures which represent Buddha in the act of fishing, an attitude which, unless interpreted in a symbolic sense, would be utterly at variance with the tenets of the Buddhist religion.”

Chinese Buddhism also employs the fish symbolism in the form of the goddess Kwanyin, the female Deity of Mercy and Salvation. “In the Han palace of Kun-Ming-Ch'ih there was a Fish carved in jade to which in time of drought sacrifices were offered, the prayers being always answered.” The fish symbol is used in funerary rites and tombs in both India and China.

“Even as the Babylonians had the Fish, or Fisher, god, Oannes who revealed to them the arts of Writing, Agriculture, etc., and was, as Eisler puts it, 'teacher and lord of all wisdom,' so the Chinese Fu-Hi, who is pictured with the mystic tablets containing the mysteries of Heaven and Earth, is, with his consort and retinue, represented as having a fish's tail.”

The symbol of the fish seems to be connected with the transition between life and death, or this world and the Otherworld, in either direction or in an apparent resurrection scenario. This explains its connection in the first instance with Orpheus and later with Christ…

"Orpheus is connected with nearly all the mystery, and a great many of the ordinary chthonic [WS: Otherworld,] cults in Greece and Italy. Christianity took its first tentative steps into the reluctant world of Graeco-Roman Paganism under the benevolent patronage of Orpheus."[R. Eisler, Orpheus the Fisher (The Quest, Vols. I and II.)]

Miss Weston even found an almost exact match:

“In Babylonian cosmology Adapa the Wise, the son of Ea, is represented as a Fisher.[Cf. W. Staerk, Ueber den Ursprung der Gral-Legende, pp. 55, 56.34] In the ancient Sumerian laments for Tammuz, previously referred to, that god is frequently addressed as Divine Lamgar, Lord of the Net, the nearest equivalent I have so far found to our 'Fisher King.'[Df. S. Langdon, Sumerian and Babylonian Psalms, pp. 301, 305, 307, 313.] Whether the phrase is here used in an actual or a symbolic sense the connection of idea is sufficiently striking.”

I hope it’s clear by now that the pivotal character of the Grail legends is the Fisher King himself. He is a semi-divine sovereign figure who protects and mediates between his people, his kingdom and the land with its unseen, but very real, ‘forces of nature’ that control the destiny of the kingdom. That there is never any mention of a physical queen in any version of the grail quest, is highly significant and demonstrates that his true Bride is the land, represented by the goddess, to whom he was joined in a sacred marriage. Christian authors and transcribers would never allow that aspect to be revealed and yet without it the various versions struggle to make coherent sense and they present the Grail as something secret, mysterious and awful, which must only be spoken of in whispered reverence, and that any exact knowledge of it was reserved for the select few.

In Miss Weston’s opinion, the Grail legend has a specific Welsh origin. Its connection to King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table, particularly Gawain in the earliest version and later Perceval (who was Welsh,) confirms this ‘Celtic’ origin.

“Galahad I hold to be a literary, and not a traditional, hero; he is the product of deliberate literary invention, and has no existence outside the frame of the later cyclic redactions. It is not possible at the present moment to say whether the Queste was composed in the British Isles, or on the continent, but we may safely lay it down as a basic principle that the original Grail heroes are of insular origin, and that the Grail legend, in its romantic, and literary, form is closely connected with British pseudo-historical tradition.”

It can be no coincidence that the earliest surviving literary version of the Grail Quest comes from Chretien de Troyes. In ‘A Quest for the Lost Realm of Faërie’ we showed how Monsieur de Troyes was a mere vassal of Marie de Champagne who worked in her ‘fiction factory’ producing romanticised and redefined versions of popular ‘Celtic’ tales. He even cites her in his introduction to ‘Le Conte de la Charrette’, or ‘The Knight of the Cart’, as providing his source material and also introducing the concept of ‘courtly love’, “although no such source texts exist today.” Source

It’s obvious that with the Grail Quest, Chretien, as he himself admits, was not inventing, but re-telling, an already popular tale.

“The Grail Quest was a theme which had been treated not once nor twice, but of which numerous, and conflicting, versions were already current, and, when Wauchier de Denain undertook to complete Chretien's unfinished work, he drew largely upon these already existing forms, regardless of the fact that they not only contradicted the version they were ostensibly completing, but were impossible to harmonize with each other.”

When Wauchier de Denain actually mentions a specific source it’s always to a well-known and authoritative collection, namely ‘Le Grant Conte’ which, just like the Mabinogi, had several ‘Branches’. The hero of this Grant Conte was Gawain, not Chretien's choice of Perceval. This confirms once again the obvious strong connection to Celtic culture as Gawain is intimately entwined with the Arthurian legend and holds the traditionally esteemed position of ‘Sister’s Son’ to Arthur. In Celtic culture the Sister’s Son is held in exactly the same regard as one’s own son in terms of respect and heredity – particularly in matters of sovereignty. We see this situation in Irish/Scottish folklore where the hero Cú Chulainn is the sister's son of king Conchobar mac Nessa. Similarly, Diarmuid Ua Duibhne is nephew to Fionn mac Cumhaill in the Fenian Cycle of Irish mythology. Tristan, the hero of the legend of ‘Tristan and Isolde’, is nephew to King Mark of Cornwall, even the Roland character in the 12th century French ‘chanson de geste’ entitled the ‘Song of Roland’, was portrayed as the sister’s son of Charlemagne and given an indestructible magic sword. In later developments, Mordred – ‘Arthur’s bane’ – is his nephew by his sister, or half-sister depending upon the version, Morgan Le Fay.

“In fact this relationship was so obviously required by tradition that we find Perceval figuring now as sister's son to Arthur, now to the Grail King, according as the Arthurian, or the Grail, tradition dominates the story.”

There are many surviving poems featuring Gawain who was, without doubt, the most popular Arthurian knight ,featuring most notably in the anonymous ‘Sir Gawain and the Green Knight’ from the late 14th century. ‘The Elucidation’ was written anonymously in the early 13th century as a prologue to Chretain de Troyes’ ‘Perceval, le Conte du Graal’ and claims its source to be a certain ‘Master Blihis’. However, with their undeniable signs of Christianisation and redefinition, these only serve to point to even earlier sources that were 'lost' a long time ago.

So, what happened to all of the original sources for the Grail Quest and all the other Arthurian material? Jessie L. Weston has this to say on the subject:

“...on the evidence at our disposal I have ventured to suggest the hypothesis of a group of poems, dealing with the adventures of Gawain, his son, and brother, the ensemble being originally known as The Geste of Syr Gawayne, a title which, in the inappropriate form The Jest of Sir Gawain, is preserved in the English version of that hero's adventure with the sister of Brandelis. So keen a critic as Dr. Brugger [WS:?] has not hesitated to accept the theory of the existence of this Geste, and is of opinion that the German poem Diu Crone may, in part at least, be derived from this source.”

That word “Geste” is a very important one...

‘gest (n.)

"famous deed, exploit," more commonly "story of great deeds, tale of adventure," c. 1300, from Old French geste, jeste "action, exploit, romance, history" (of celebrated people or actions), from Medieval Latin gesta "actions, exploits, deeds, achievements,"’ Source

In quite a few previous articles, we have discussed the deliberate and ruthless destruction of manuscripts concerning early English history. We have drawn attention to a certain Polydore Vergil in particular. Rather than repeat it all again, this link also leads to all of the previous material. Suffice it to say that this character is almost single-handedly responsible for the obliteration of early English history and also its redefinition. Both he and his ‘patron’ back in Rome were determined to remove all and any evidence to show that King Arthur was a genuine historical figure. Obviously the same kind of purge occurred on the continent.

Another feature of Felix’s article ‘King Arthur in Hyperborea & the Arctic Cataclysm’ was the seemingly persistent claim that Arthur had ruled over a much larger kingdom than just Britain. Felix demonstrated that the source of this claim pre-dates the 1199 text known as ‘Insule Britannie’ and comes from a book known as ‘Gestae Arthuri’. This book was ‘lost' even in John Dee’s time, but the ‘Insule Britannie’ and also another known as ‘Leges Anglorum’ of 1210, also mention this extended kingdom, but they are ‘Christianised’ and redefined versions of the original ‘Gestae Arthuri’. John Dee himself gives an account of King Arthur’s expedition to the Arctic Pole that he states comes directly from “the beginning of the Arthuri Gestis” (discussed here) and it’s this same expedition that many believe to be the same as that recounted in the poem ‘Preiddeu Annwn’, or ‘The Raid on the Otherworld’ from The Book of Taleisin.

I submit that the Arthuri Gestis, or Geste of King Arthur, along with the Geste of Syr Gawayne, comprised the original source of the Grail Quest, the true extent of King Arthur’s kingdom and all of the other Arthurian redefinitions.

We’ve seen that The Grail is intimately connected with The Sovereignty of the land and the physical and moral sanctity of the monarch. This Sovereignty is granted by the appropriate deity, either god or goddess, and held in trust by the chosen monarch and/or his surrogate (such as the Sister’s Son in the Celtic tradition.) Any physical or moral blemish incurred by the monarch or his surrogate, or breach of the geasa, results in The Wasteland.

The Christianised Grail Quest romances are all derived from earlier sources which are ‘Celtic’ in nature. The Quest element is a throwback to that very Celtic culture that inspired the later romances whereby various tasks must be performed successfully in order to achieve The Grail. In the original Celtic tradition the goddess would test the integrity of any prospective or existing monarch (or surrogate) by setting him particular tasks or even goading him into taking one course of action or another. These tasks would often involve trips to The Otherworld.

If we recognise that the 10th century cataclysm turned much of our world into a Wasteland and also saw the end of an era with the rise of a new Christian ideology, is it not reasonable to ask if this was the result of some kind of catastrophic breakdown in the relationship between the chosen monarch and the goddess, between this realm and The Otherworld?

If the geasa itself is The Grail – the agreement or contract between our world and The Otherworld, between humanity and the unseen Forces of Nature – then the cataclysm and the ensuing Wasteland were the result of the Grail’s loss. Furthermore, if we also consider the speculation voiced in the article ‘The History Revolution of the Early 20th Century’ regarding the possibility of a cyclic millennial ‘energy’ for change, then the 10th century cataclysm qualifies as much as our own present situation does now. It also becomes obvious why this ‘Grail’ or geasa had to be kept secret, or rather only made available to the select few, how it has been misused and why it has been demonised as ‘contracts with the devil’ etc.

Having reached this point, it’s time to see if there’s any evidence to support the preceding hypothesis, which will be the subject of the next article. I could go on in this one, but that would delay the publication of the material presented above and I would be in danger of rushing the following part, which it doesn’t deserve.

I will be looking into the Grail’s legacy from the Knights Templar, through the Rosicrucians with their 'Sacred Alchemical Weddings' not forgetting Freemasonry. Then also into the Cult of the Severed Head and its relation to Bran the Blessed, which involves a possible ‘trigger’ event for the Wasteland / Cataclysm. No doubt there will be a shed-load of other stuff as well by the time it gets published.

In the meantime I would like to leave you with something ...curious. I realise that many people despise the monarchy these days and that many of them are indeed despicable. It’s even been suggested that those whom we believe to be royal personages are actually doppelgängers. It’s also worth noting that, astrologically, we are in a period where Pluto is emphasising the cycles of life, death, rebirth and particularly transformation – the very concepts we have been discussing here. The Grail, or the geasa, is still lost and was broken a long time ago, maybe a new geasa was established with different malevolent gods – who knows – but the kings, queens and 'rulers' are all ‘wounded’, corrupted and highly defective. In so many ways the land is still a Wasteland and set to become even more so at an ever increasing rate with each new policy these maniac bureaucrats devise.

The following quote was made by the Prince of Wales in 2002, who is now Charles III of Great Britain…

‘I have come to realise that my entire life has been so far motivated by a desire to heal – to heal the dismembered landscape and the poisoned soul; the cruelly shattered townscape, where harmony has been replaced by cacophony; to heal the divisions between intuitive and rational thought, between mind and body, and soul, so that the temple of our humanity can once again be lit by a sacred flame.’ Source

He has recently been out of circulation, although now he is back, apparently ‘healed’ from a ‘cancer’. Is it too much to expect that he will at least try to live up to what he claimed to be the motivation of his entire life? In his younger days he used to champion causes that were genuinely worthwhile, but immediately ridiculed - a hopeful sign... a great deal of dirty water has passed under the bridge since then and I wonder how much damage that contamination has caused.

TTFN!

The Dark Earth Chronicles Part One

The Dark Earth Chronicles Part Two

The Dark Earth Chronicles Part 2.5

Editorial Update March 2024

The ‘History Revolution’ of the early 20th century

The Grail, The Cataclysm, The Wasteland and Our Lost Ancient Sovereignty

Updates and Re-Evaluation

Taliesin, The Divine Poisoner

Will Scarlet

.

IF YOU ARE SEEING A LINK TO MOBIRISE, OR SOME NONSENSE ABOUT A FREE AI WEBSITE BUILDER, THEN IT IS A FRAUDULENT INSERTION BY THE PROVIDERS OF THE SUPPOSEDLY 'FREE' WEBSITE SOFTWARE USED TO CREATE THIS SITE. THEY ARE USING MY WEBHOSTING PLATFORM FOR THEIR OWN ADVERTISING PURPOSES WITHOUT MY CONSENT. TO REMOVE THESE LINKS I WOULD HAVE TO PAY A YEARLY FEE TO MOBIRISE ON TOP OF MY NORMAL WEBHOSTING EXPENSES - WHICH IS TANTAMOUNT TO BLACKMAIL. I CALCULATE THAT THEY CURRENTLY OWE ME THREE MILLION DOLLARS IN ADVERTISING REVENUE AND WEBSITE RENTAL.