Well hello again, I hope this article finds you in good spirits and I apologise for the long delay in producing this new one. There seems to be an increasing clamp-down on access to research material on the internet lately. Sites that once bypassed paywalls have recently either disappeared or transformed into ‘registered users only’ or ‘premium services’. Internet searches have also become far more stupid – a sure sign of Ai. We’re also now seeing more and more gatekeepers appearing, even on primetime TV.

Anyway, enough of all that, let’s get cracking on the Dark Earth Chronicles. I want to take a closer look at Taliesin and his place within the accumulation of created mythologies, which have developed into an accepted body of scholarly reference. Who was he really and why was he presented as both a champion of Christianity and a product of the pre-Christian Druidic ‘tradition’? Hopefully, this re-evaluation will also shed more light upon the enigmatic poem, ‘Preiddeu Annwfn’.

● Preiddeu Annwfn’s association to the Cataclysm

● The Man from H.E.N.G.W.R.T. ● Iolo Morganwg ● The Backlash

● Would the real Taliesin please stand up… ● Hanes Taliesin Synopsis

● The Fallout from The Hanes Taliesin ● The Rise of the Druids

● Multiple Personalities and Disorder ● Reincarnate Bards

● “You’re Bard!" ● Retro‑fitting the Past with the Present

● Guilt‑free Paganism ● Taliesin the Psychopath

● Operation De‑Euhemerisation ● Llyfr Taliesin (The Book of Taliesin)

● Preiddeu Annwfn, The Plunder of the Otherworld

● Will the real Gweir please stand up... ● Am I not honoured in praise?

● The Isle of the Strong Door ● Preiddeu Annwfn ‑ The Verdict

● A Snapshot of the Facade

Regular readers will know that the poet Taliesin, and in particular his poem, Preiddeu Annwfn, have played a significant role in The Dark Earth Chronicles. It first appeared in Felix’s article ‘King Arthur in Hyperborea and the Arctic Cataclysm’ where it was linked to the events reported by Dr John Dee and Gerardus Mercator that were set out in a mysterious book known as ’The Inventio Fortunata’. These involved the colonisation of lands surrounding the North Pole by King Arthur, which coincided with information from another ‘lost’ book – The Deeds of Arthur’. Felix wasn’t the first to link the Preiddeu Annwfn poem to these events, but his suggestion that it had some bearing upon the cataclysmic deluge, when incredible quantities of ‘muck’ descended upon the Arctic Circle, was unique. It became even more significant when the Arctic deluge was successfully shown to have been an intrinsic part of the wider Dark Earth cataclysm of the 10th century.

Recently an issue has arisen concerning the above. The connection between the poem Preiddeu Annwfn and King Arthur’s colonisation of the Arctic doesn’t really work. The colonisation information from ‘The Deeds of Arthur’ is quoted by Dr John Dee, but he states that it comes from “the beginning” of that book. If the 10th century cataclysm saw the end of Arthur’s reign then there would have been no further deeds to write about in ‘The Deeds of Arthur’ and no islands around the North Pole to colonise. Therefore, given that the poem ‘Preiddeu Annfwn’, or The Spoils of Annwn / The Raid on Annwn has nothing to do with colonisation, that connection is not valid. Where it is made, it relies upon the number of ships that returned from the ‘raid’ on Annwn in the poem, being the same as the number of ships that made land in the colonisation event – seven. However, that same number crops up frequently in old Celtic stories. For example, only seven returned from the war with Ireland including the wounded Bran the Blessed, and Taliesin, in the Mabinogi tale. Furthermore, the seven that survived the supposed raids are more probably individuals rather than actual ships as we will see, besides, perhaps the poem isn't even about an actual raid on the Otherworld.

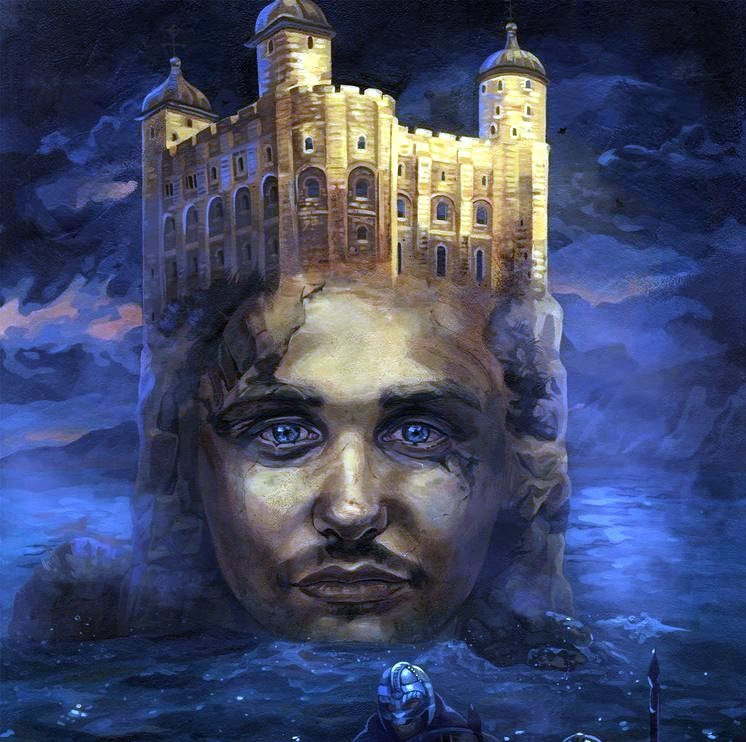

The Head of Bran the Blessed buried beneath Tower Hill in London. Source

This in turn raises another issue. The colonisation voyage was clearly defined as being to islands within what the later ‘Greeks’ called Hyperborea, and we now call the Arctic Circle. The location of the Preiddeu Annwfn, or Raid on Annwn, is never specified. All that can be determined about it from the poem is that it had to be reached by ship and that it was in The Otherworld – two seemingly contradictory statements.

To try and understand where the poem Preiddeu Annwfn fits into the overall picture, if at all, I decided to take a closer look at its supposed author – Taliesin.

To begin with, let’s take a look at the origin of the current Welsh/British accumulation of created mythologies and tales regarding ‘The Great Bard’ Taliesin...

“Robert Vaughan (1592? – 16 May 1667) was an eminent Welsh antiquary and collector of manuscripts. His collection, later known as the Hengwrt–Peniarth Library after the houses in which it was successively preserved, is what forms the nucleus of the National Library of Wales, and is still in its care.” Source

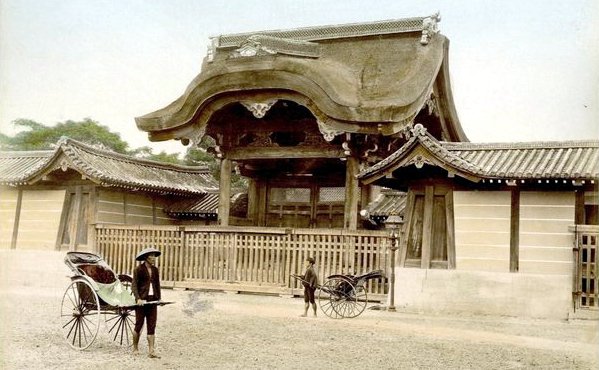

Hengwrt (1793) engraving by John Ingleby

Public domain

Nothing is known of this Robert Vaughan bloke until he turned up at Oriel College, Oxford, in 1612 which he later left before finishing his degree. Then we’re told that he ‘settled’ at “the mansion of Hengwrt (English: Old Court), Llanelltyd, near Dolgellau, north-west Wales, which had belonged to his mother's family.” (ibid.) Hengwrt was once a grange of the Cistercian Cymer Abbey, but was given to Sergeant at Arms, John Powys, along with the rest of the Abbey’s property, after the Protestant Reformation. Hengwrt “was eventually bought by Hywel Vaughan of Gwengraig, after which it remained in the Vaughan family for many years.” (Source) Then we find out that this Hywel Vaughan was the father of our Robert Vaughan. Therefore, Hengwrt was in the possession of Robert Vaughan’s father – so there’s an anomaly straight away regarding our Mr Vaughan, as the only way it could have “belonged to his mother's family” is if she was related to Sergeant at Arms, John Powys. Anyway, like many ‘gentry’ our Robert was keen on early Welsh history and genealogy and so began collecting manuscripts and books in his library at Hengwrt. He also transcribed texts himself and translated the Brut y Tywysogion (or Chronicle of the Princes) into English. He wrote several short historical tracts along with a book entitled ‘British Antiquities Revived’, published at Oxford in 1662...

“He was able to increase his holdings further after making an arrangement with the calligrapher and manuscript collector John Jones of Gellilyfdy , Flintshire, in which one would combine both collections on the other's death.” (ibid.)

There we have another member of the Welsh gentry coming into the picture. Mr Jones was also a lawyer and a scribe. He came from a family of manuscript collectors and would ‘copy’ (nudge-nudge-wink-wink) manuscripts found in houses of the Welsh gentry. By 1611 his legal career was pretty much over and he spent most of his remaining days in various debtor’s prisons. It was whilst incarcerated that he did most of his ‘transcribing’ (another nudge-nudge-wink-wink.)

“His first manuscript copy was made in 1598, and he went on to make over a hundred further volumes. Later characterised as a rather indiscriminate copyist, Jones transcribed works on a vast range of subjects: in addition to his interests in law, poetry and history, he may in part have worked simply to relieve the stresses of imprisonment, [WS: or pay off his debts] as he would obsessively recopy or re-arrange existing works when no new materials were available… Jones was not only a copyist but was also a notable calligrapher, designing many of his own capitals and tail-pieces and adopting others from Italian models.” Source

Well, Robert Vaughan ended up possessing Jones’ entire library, mostly through their agreement, but also because Vaughan would accept books and manuscripts from Jones as repayment of loans. It’s possible that Vaughan was lending money to Jones to pay off what were most likely gambling debts, knowing that he would receive books and manuscripts in lieu of cash that may well have been worth considerably more than the debt. This combined collection became the basis of the current National Library of Wales, as stated previously.

It’s the heritage of this university drop-out and his incarcerated forger, that has given us the tradition of the Cornish (not Welsh) Prydein ab Aedd Mawr who “subdued the whole island” in other words, The British Isles, which was then named after him - Prydein. However, the Cornish for Britain is ‘Breten Veur’, not Prydein, and there’s no Old Cornish or Middle Cornish, because it developed from Common Brythonic… so we’re back to Bride, Bryth and Brigid as being the origin of ‘Britain’ and the whole business of the Welsh ‘Prydain / Prydein’ giving the name ‘Britain’ seems unlikely.

Let’s not forget that this all took place shortly after the Protestant Reformation in England, some 500 or so years after the original Welsh tales had been redefined by the Christian scribes and monks. Is it any wonder that what we have been left with following these various assaults, is a seemingly inscrutable pot-pourri of fantastical events?

One of Vaughan’s sons was made a Baronet in 1791 and his son (the Baronet's) went on to become a long-serving Tory politician. One of Robert Vaughan’s daughters became a Quaker who emigrated to Pennsylvania, America, in the late 17th century. Perhaps she was the ancestor of the Robert Vaughan who played Napoleon Solo in the original ‘The Man from U.N.C.L.E. TV series (nudge-nudge-wink-wink.)

Born in 1747, Edward Williams was his given name, but he took the ‘Druid’ name of Iolo Morganwg...

“He summed up his achievements as follows: ‘Iolo Morganwg, author of a book of English poetry priced one pound, Welsh psalms priced a shilling, a stonemason, builder, wall-shutter of Flemingston cemetery, Bard of the Society of Welsh Unitarians, Leader of the fools of the island of Britain’” Source: 'A Rattleskull Genius’, edited by Geraint H. Jenkins, 2005

It’s interesting to see the name ‘Flemingston’, which obviously means ‘town of the Flemings’ – their arrival in Wales, not so long after the Norman Conquest, was another devastating event for the area which has been covered in previous articles. Anyway, today Iolo Morganwg is pretty much forgotten, ignored and even disdained. When he does get a mention, his name (names) are usually incorrectly spelled – often deliberately so, in order to cause maximum offence and ridicule, even though he’s been long dead..

His story took place against the dramatic changes brought on by industrialization and modernization. Romanticism, Evangelicalism and the Enlightenment were the big issues of the day. Romanticism blurred the boundary between: the arts and the sciences, whereby original manuscripts were indistinguishable from printed material, and creative fiction was passed-off as academic factual writing. I don’t think it’s purely coincidence that Romanticism features that same “Roman” word.

“He [Iolo] was a child of his age. Throughout Europe imaginative myth-makers were transcribing, annotating, mimicking and fabricating a mass of literary and historical material in order to fill or supplement what they believed to be inexplicable gaps in the record. The nostalgia for past glories, both real and imaginary, was coupled on the part of the public with a subliminal desire to be taken in as thoroughly as possible. Macpherson’s Ossian captivated readers and writers far beyond Scotland and it was translated into every major European language. On the Continent, too, there are significant comparative contexts for the kind of nation-building which Iolo advocated. As R. J. W. Evans demonstrates in his analysis of the culture and politics of forgeries in central Europe, making the past a glorious, attractive and integral part of national ideologies and aspirations became de rigueur among marginalized ethnic groups. In Elias Lönnrot’s imaginative Finnish epic, the Kalevala, in Théodore Hersart de La Villemarqué’s creatively edited collection of Breton songs, the Barzaz-Breiz, and in Vác[es]lav Hanka’s counterfeit early Czech manuscripts, Rukopis zelenohorský and Rukopis králo[vé]dvorský, we see (as did Iolo) how the growing power of nationality was based on a reinvented, usable past. Thus, to describe Iolo merely as a confidence trickster, a charlatan and a rogue is to miss the point.” (ibid.)

Iolo Morganwg

Source

Missing the point or not, the fact remains that he has contaminated the past even further through his forgeries, however brilliant they may have been. His main achievement was to compose ‘brilliant’ poems in the classical Welsh cywydd style and publish them in 1789 as being the authentic work of a certain Dafydd ap Gwilym. The success that he had with this deception encouraged him to go even further...

“...he then began to spin fabulous tales, fabricate brutiau (chronicles), conjure up imaginary poets like Rhys Goch ap Rhicert, develop the ingenious metrical system called ‘Glamorgan Measures’ (‘Mesurau Morgannwg’), and infuse hundreds of bogus triads and epigrams with memorable shafts of wisdom.” (ibid)

(Please note the ‘bogus triads’ comment as it reinforces a particular ‘pet-hate’ of mine regarding the Welsh Triads).

He was a complicated cocktail of inferiority, national pride and pure ego mixed with genius. He had an in-depth knowledge of his subject and was able to compose his forgeries using selections from his memory of genuine original sources. Furthermore, as he knew that medieval chroniclers had quite freely omitted certain material, added other events from memory, or redefined and embellished it, Iolo himself felt quite justified in his own fictitious creations. Regardless of his motives, he redefined Welsh history and gave the Welsh people a renewed sense of identity as a distinct race with a distinctive legacy... even if it was all mostly based on fantasy.

Following the success of his poetic forgeries, published in the same year as the French Revolution, Iolo became ‘Bard Williams’, a poet descended from the ancient British Druids. Under this new guise, he spent some time in London and became the darling of London society. However, he paid a heavy price for this and soon became addicted to laudanum, although even that failed to dull his enthusiasm, which he turned towards a new mission of changing the present in just the same way as he had already changed the past.

Iolo Morganwg

Source

Inspired by Tom Paine’s ‘Rights of Man’, Bard Williams became the ‘Bard of Liberty’. He turned his bardic skills against society in a persistent barrage of essays, pamphlets against monarchies, the aristocracy, the priesthood and all war and violence. This obviously led him into direct conflict with the law on numerous occasions, many involving court appearances, fines and prison sentences. However, his writings were significant enough to be noticed by the likes of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, the poet, critic and philosopher, and the poet William Wordsworth, who between them launched the English Romantic movement and, actually cited Iolo Morganwg’s work in their attempts to discredit the powerful philosophical arguments presented by the political theorist, anarchist and novelist William Godwin in his ‘An Enquiry concerning Political Justice’ (1793.)

It was during this period that he establish the first modern Welsh national institution – the Gorsedd of the Bards of the Isle of Britain (Gorsedd Beirdd Ynys Prydain) in 1792. Today it is described in this manner…

“The Gorsedd of the Bards includes poets, writers, musicians, artists and individuals who have made a contribution to Wales, the language, or its culture.”

The Gorsedd of the Bards of the Isle of Britain

Source

However, when Iolo returned to Wales in 1795, he had other plans. The Gorsedd became a vehicle for his own particular form of ‘bardism’, which involved radical dissent and the democratic cause. This was further enhanced by his forthright support for what was then called anti-trinitarianism (denial of the Christian Trinity,) but which is now called nontrinitarianism for some reason. With another twist of his Bardic identity he became the ‘Bard of the South Wales Unitarian Society’ who continued to rant against injustice even up until 1818.

History, as well as his own experiences, had made it clear to Iolo that the decision-makers in London were so hostile to the Welsh cultural identity that they could never represent its interests. He believed that, without a national university, a museum or a library, the Welsh would remain a neglected and marginalized people. He was obsessed by what he called ‘yr hen ddywenydd’ (the old happiness)…

“...by which he meant the study of the language, literature and history of his native land, especially his beloved Glamorgan, he believed that history was important because it helped people to understand the present as well as the past, and because it could be summoned for use in the construction of nations.” (ibid.)

Personally, I’m not convinced that’s what he meant by “the old happiness,” apart from the fact that it doesn’t really make sense. I would say that it relates to a previous lost time, when the world was a different place, but we will never know.

Between 1801 and 1807, Iolo produced his three-volume epic entitled ‘The Myvyrian Archaiology of Wales.’ Myvyrian relates to Owain Myfyr who was once the owner of the Myvyrian Collection of manuscripts, which allegedly contributed to Iolo’s magnum opus. Through his genius for combining genuine sources with his own imagination, and wrapping it all up in his own particular subjective vision, Iolo gave the Welsh people a new identity. He revived, or created, (depending on your point-of-view,) Welsh culture… or maybe that should read, revived and created Welsh culture. His impact upon both the Welsh Language and Welsh culture, was real, profound and dramatic, but let’s not forget – this new cultural identity was created from Iolo’s personal vision and his own particular interpretation of the past. We should also be aware that this same process was also going on in many other cultures during the same period… one could even include the French and American revolutions within this same phenomena.

For many years Iolo was ridiculed and demonized for ‘preying on the naivety of his countrymen.’ He engendered deep resentment in those who had been fooled by his forgeries – especially those who held high office in institutions and who really should have known better. Iolo had no shame regarding his forgeries, but believed that he was simply following a tradition… which to a certain extent is absolutely true. His fifty year addiction to laudanum, which is a tincture containing 10% opium, no doubt played its part in his… what shall we call them – delusions? Perhaps it heightened his mental abilities, allowing him to make significant connections between the vast amounts of information stored in his mind, or maybe it made him more open to… let’s call it inspiration?

Whatever the case, one of the most significant developments, that can be directly ascribed to Iolo, is that by the mid-Victorian period Neo-Druidism was flourishing in all its glory. Whether there ever was a Paleo-Drudism in the first place was irrelevant, as was the difference between a Bard and a Druid. This took place not only in Wales, but also in England.

Much of the information cited above comes from ‘A Rattleskull Genius, The Many Faces of Iolo Morganwg’, edited by Geraint H. Jenkins, 2005.

After Iolo Morgannwg had done his thing, well, according to Professor Marilyn Butler anyway, the use of myth in poetry in the eighteenth and early nineteenth-century ‘English Romanticism’ period was generally associated with detachment from the Church and secular radicalism, no doubt as highlighted by the rise of Neo-Druidism. To combat this, British clergymen produced massive works to try to prove that Paganism, the source material for contemporary mythologisers, postdated and was a corruption of Judaism. Their mission was to reduce the status of all Pagan myths to ignorant misinterpretations of the Old Testament.

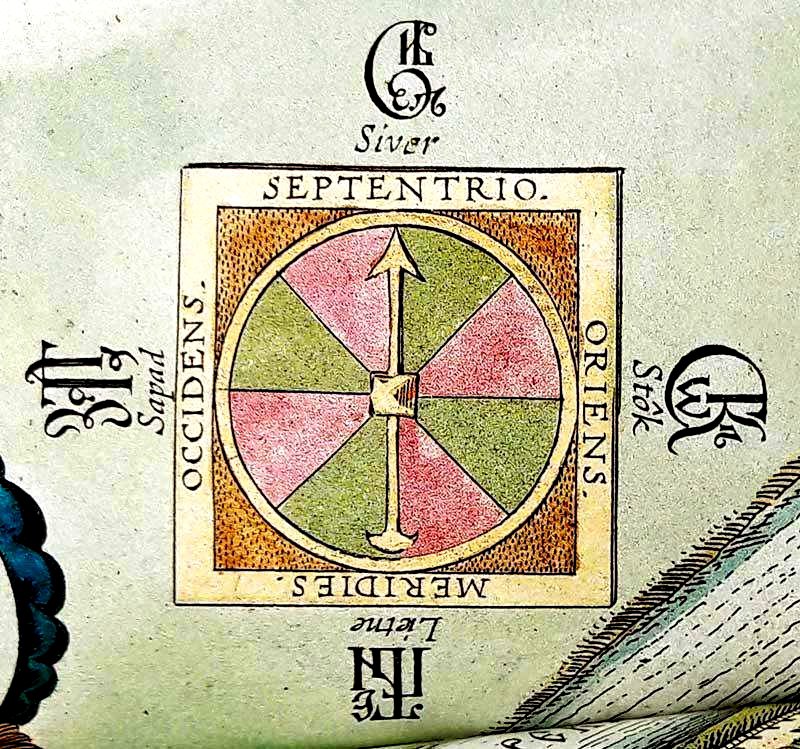

Thomas Maurice tackled Hinduism in 1792, G.S. Faber focused on the Greeks in 1816, and Edward Davies addressed Celtic Paganism (i.e., Druidism) between 1804, with his ‘Celtic Researches’, and 1809 with ‘Mythology And Rites’. Davies took his inspiration from Jacob Bryant, whose 1774 ‘Analysis Of Ancient Mythology’ proposed that because Pagan religions referred to a great flood, it ‘proved’ that their believers remembered the Biblical Deluge and the Ark. Therefore, this demonstrated that Paganism was merely a misunderstanding of the only ‘true’ religion. Davies took up the exact same sword. At the end of the second section of ‘Mythology And Rites’, Davies claims that the Druids ‘recognized the character of the patriarch Noah, whom they worshipped as a god, in conjunction with the sun’. He also claims there was a Goddess representing the Ark, whom he identifies with Cerridwen.

“It is a mythological allegory, upon the subject of initiation into the mystical rites of Ceridwen. And though the reader of cultivated taste may be offended at its seeming extravagance, I cannot but esteem it is one of the most precious morsels of British antiquity, which is now extant.” Source E. Davies, ‘The Mythology And Rites Of The British Druids’ (1809.)

Of course, Mr Davies has no idea of exactly how the mythology and rituals of the British Druids related to these “mystical rites,” but insists they are based upon a misunderstanding of the Jewish Old Testament, which is simply stupidity ...jewpidity even. This attitude and general climate, is important to bear in mind as we proceed with our quest to track down “The Bard” Taliesin and the origins of Druidism… well, my quest.

So, finally, let’s take a look at the Taliesin as defined by the Hanes Taliesin (History of Taliesin.) This collection of Welsh prose and poetry is a supposedly autobiographical account of the early life of the poet Taliesin. The oldest recorded version dates from in the mid-16th century and was written by one Elis Gruffydd. The tale was also recorded by our old friend John Jones of Gellilyfdy (c. 1607,) although unsurprisingly, it differs slightly from the earlier version. No doubt due to him fiddling with it when he was bored in prison. Whilst none of the poems or prose in the Hanes Taliesin appear in The Book of Taliesin, there are fragmentary coincidences between them. Many ‘scholars’ see a resemblance to the story of the boyhood of the Irish hero Fionn mac Cumhail and the salmon of wisdom, although personally I find that rather vague and based mainly on the common occurrence of the word “salmon,” but there is a connection to the tale of Saint Patrick, as we will see later.

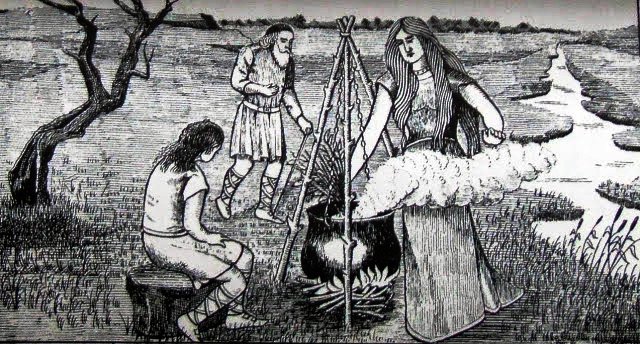

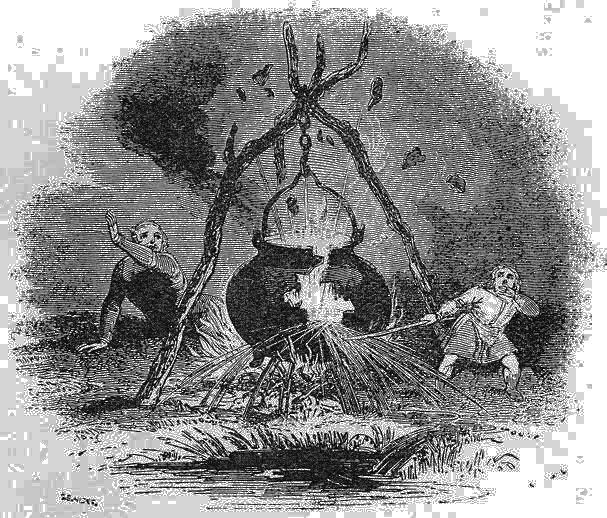

Gwion Bach, Morda and Cerridwen

with the Cauldron of Life Source

Before we get into further discussion about the Hanes Taliesin, it’s important to know some more about it...

Taliesin was born in the days when King Arthur ruled. He was known as Gwion Bach in those days and he became a servant to the Goddess Cerridwen. Let’s not forget, this ‘original’ tale has already been redefined through copious euhemerism, so in this previously laundered version, Cerridwen is not a Goddess, but a ‘Magician’ who was married to a nobleman called Tegid Foel. Within Tegid Foel’s patrimony was the largest natural body of water in Wales, known today as Llyn Tegid (Bala Lake,) in Gwynedd, Wales, which is fed by the River Dee. We should not ignore the fact that many Celtic Goddesses were associated with lakes, rivers and wells – Cerridwen and Brigid being no exceptions, not forgetting the ‘Lady of the Lake’.

Llyn Tegid (Bala Lake,) Gwynedd, Wales.

Source

So, Cerridwen was a ‘sorceress’ who was adept in enchantment, magic, and divination. She had two children by her nobleman husband, a daughter who was beautiful, and an extremely ugly son whose name was Morfran, meaning ‘Great Crow’ or some say ‘Sea Raven’. There has to be some connection there to The Morrigan or even Bran the Blessed, both of whom were associated with crows or ravens. Later on Morfran became Afagddu, meaning "Utter Darkness" (not to be confused with the 1984 song “Agadoo doo doo, push pineapple, shake the tree” by Black Lace.) In other versions, Cerridwen had three children. So, Cerridwen sought to use her gifts to invoke the qualities of great wisdom and knowledge in her son in order to compensate for his appearance. (Why didn’t she just make him look handsome?) To this end she prepared a special concoction in her magic cauldron which had to be stirred constantly for one year and a day in order to produce this ‘Inspiration’ or Awen.

The job of cauldron stirrer was assigned to a blind man named Morda. The young Gwion Bach (Taliesin), was given the job of keeping the fire going beneath the cauldron. It’s important to know that in this ridiculously contrived story, it was only the first three drops of this mixture that would make Morfran "extraordinarily learned in various arts and full of the spirit of prophecy." The remaining mixture inside the cauldron would be as powerful a poison as there could be in the world, which would shatter the cauldron and spill the poison across the land. It’s then claimed that Cerridwen sat down, and accidentally fell asleep after all her hard work gathering herbs and stuff. Anyway, as you might imagine, this was the perfect opportunity for something unexpected to occur, which it did when suddenly the first three drops ‘emerged’ from the cauldron. Gwion Bach barged the old blind man aside and snaffled the three drops for himself, whereupon he instantly became wise and all-knowing. In other versions he pushed Cerridwen’s son, Morfran, aside in order to get to the 3 drops. Fortunately, he became wise enough to know that as soon as Cerridwen woke up, his arse would be toast, so he legged it… had it away on his toes… scarpered. (Source: ‘The Cockney Translation of Hanes Taliesin’… nudge-nudge-wink-wink.)

The cauldron itself uttered a cry and then shattered from the strength of the poison. Exactly how Cerridwen would have avoided this same occurrence is never mentioned, of course. Anyway, presumably the contents then spread across the land, but I could only find one reference to the horses of Gwyddno Garanhir, who were drinking at the banks of a river and poisoned by the shattered cauldron. They died a horrible death. This Gwyddno character should be remembered for later.

Cantre'r-Gwaelod

Source

Anyway, sure enough Cerridwen awoke and immediately took off after Gwion. There then followed a shapeshifting marathon. Gwion became a hare so Cerridwen pursued him as a greyhound. He became a fish in a river so she became an otter. He became a bird and she responded with a hawk. Finally, Gwion was forced into a barn where he became a grain (or seed) of corn, so Cerridwen, in the guise of a tufted black hen, ate him.

Unfortunately, having not taken the proper precautions, Cerridwen became pregnant. Knowing she was carrying Gwion, she decided to kill him as soon as he was born… which is again ridiculous, as being a gifted sorceress, she could have killed him at any time, in fact you wouldn’t even need to be a sorceress to do it. Anyway, when the time came, nine months later, she couldn’t go through with it because baby Gwion was so beautiful. Instead she had him put into a hide covered basket and thrown into the lake, river, or sea, depending on the version of the tale. This has a very familiar ring to it and can be added to the list of Darab (in the Shahnameh,) Sargon the Great and of course Moses – which is the smoking gun.

Obviously at least nine months had passed from the time that the cauldron’s poison had spread out across the land, but there is still no mention of its effects during that period. Furthermore, Gwion Bach wasn’t found until after he had been in the makeshift coracle, floating about in the sea, (or a lake, or a river,) from the beginning of King Arthur’s time until about the beginning of King Maelgwn Gwynedd’s time, which someone estimated to be about forty years. What chronology was used to make that calculation is anyone’s guess. So, Arthur had supposedly gone during that period, but again, no mention is made of the effects of the poison that spread across the land. If this chronology is correct, then how did Taliesin manage to accompany Arthur in the poem Preiddeu Annwfn?

As always, although maybe 40 years late, the basket, complete with baby, was found by Elphin, another nobleman and son of Gwyddno Garanhir, 'Lord of Ceredigion' who was in the service of King Maelgwn and the same fella whose horses were poisoned earlier. It was All Hallows Eve (31st October) and Elphin was fishing for the salmon that were always found caught in the weir at that particular time on the shore of the river Conway, adjacent to the sea. In recent times, a storm revealed a submerged forest and a weir at that very location. However, on that particular Halloween, there were no fish whatsoever caught in the weir, just Cerridwen’s bundle. Upon closer examination, Elphin was not only shocked to find a baby, but also by the appearance of its forehead, to the point where he exclaimed "this is a radiant forehead!" (We’re told in the text that tal iesin, means radiant or shining head or forehead in Welsh, but the modern form contradicts this as ‘talcin’ is forehead and neither radiant nor shining are anything even vaguely resembling ‘iesin’.) Upon being named ‘Taliesin’, the child replied (in the third person) saying, “Tal-iesin he is!” He began to sing some poetic stanzas, known as ‘Dehuddiant Elphin’.

The infant supposedly sang these stanzas all the way from the weir to Elphin’s house. They are full of overtly Christian references with promises of riches to come for Elphin and his father, Gwyddno Garanhir - he of the poisoned horses. Together with his wife, Elphin raised Taliesin with love and affection and, just as predicted, Elphin's wealth increased daily, as did his father’s, along with their standing with the King.

Predictably, Elphin became too proud, which eventually caused him to get in trouble with King Maelgwn Gwynedd, but his wonderful son, Taliesin, saved him. The details are quite silly and involve senseless boasting on Elphin’s part regarding the chastity of his wife and the prowess of his bard being superior to those of the King’s. This landed him in the dungeons. Taliesin came to the rescue and ‘arranged matters’ so that in the end Elphin was released and back in favour (not to mention rich.) Taliesin became famous and was recognised as the finest of the bards by King Maelgwn Gwynedd. After a phenomenal amount of Christian Evangelising and wild claims that Taliesin was known to John the Baptist as “Merlin,” the tale ends with Taliesin giving prophecies to King Maelgwn about the origin of the human race and what will now happen to the world… although quite how you can predict the origin of the human race I'll never know.

“It is a great pity Taliesin is so obscure, for there are many particulars in his poems that would throw great light upon the history, notions, and manners of the ancient Britons, especially the Druids, a great part of whose learning it is certain he had imbibed.” (Source ‘Specimens’ by The Rev. Evan Evans, 1764.)

That’s quite a strange statement really. If the poems are obscure how is it possible to claim that the details, or “particulars,” of them would provide anything useful? Equally, how can anyone say that Taliesin was familiar with the learning of the Druids if the poems are so obscure? It’s like putting the cart before the horse. Also the use of the word “imbibed” shows that the Reverend was familiar with the Hanes Taliesin tale where Gwion imbibed the three drops of Cerridwen’s potion.

The entire story has since been divided into two strands, or sections. One is known as the Gwion Bach strand and the other as the Elphin strand. The Gwion strand was mostly ignored and even the supernatural elements of the Elphin strand were downplayed or redefined until the second half of the nineteenth century. At this point emphasis shifted to the Gwion strand, when it was seen as a religious allegory with the potential to uncover the mysteries of Druidic doctrine.., just like the Rev. Evan Evans had done back in 1764 when he put the cart before the horse.

During the period within which we have just been following the antics of Iolo Morganwg, many ‘scholars’ addressed the issue of the Hanes Taliesin (History of Taliesin) myth. Many were reluctant, perhaps even scared, to describe magical episodes in detail. Very few drew attention to the Gwion version where mention is made of a great flood, specifically – “Gwyddno Garanhir, was a petty king of Crantre’r Gwaelod, whose country was drowned by the sea, in a great inundation that happened about the year 560.” That date coincides with one of Gunnar Heinsohn’s triplicated 10th century cataclysm dates. This is the same Gwyddno Garanir whose horses were poisoned by the spilling of Cerridwen’s caudron… a strong reference to the cataclysm you might say.

As well as developing arguments against the Hanes Taliesin and Paganism in general, by concocting matches between characters and symbols and then assigning them to archetypes from the Biblical Flood, very poor etymological arguments were also used along with comparisons to other Welsh material that had already been heavily manipulated in the distant past. For example, Cerridwen’s husband, Tegid Foel, is equated with Noah, whilst Cerridwen herself is bizarrely equated to the actual Ark. One ‘scholar’ suggested that the Hanes Taliesin relates to succession ceremonies, by which the ancient Britons commemorated the history of the deluge.

While most saw a Biblical foundation corrupted by Pagan ignorance, it took a long time before others would see the story of Pagan figures corrupted by Christian censorship. Prior to 1830, the whole of the English-speaking world’s access to the Hanes Taliesin, comprised a scattered collection of summaries, the notions of a cleric with an agenda, and an eccentric novel, all of which excluded most of the supernatural content of the medieval tradition.

Between 1830 and 1850 research on the Hanes Taliesin continued, but in much the same vein. The only translation of it during the nineteenth century was when it appeared in the first version of the ‘Mabinogion’, which was the fruit of the labours of William Owen Pughe and Lady Charlotte Guest. It was also the first to be published in a modern print format.

Lady Charlotte Guest

Source

It’s very interesting to note that the Hanes Taliesin has been omitted from just about every English-language translation of the Mabinogion since then (1849.) Lady Charlotte also collected several short biographies on Taliesin which most scholars believe to be forgeries by Iolo Morganwg. An extract from her copious notes is worth relating:

“Taliesin, chief of the Bards... being once fishing at seas in a skin coracle, an Irish pirate ship seized him and his coracle, and bore him away towards Ireland; but while the pirates were at the height of their drunken mirth, Taliesin pushed his coracle to the sea... he was found by Gwyddno’s fishermen, by who he was interrogated; and it was when it was ascertained that he was a bard, and the tutor of Elffin, the son of Urien Rheged, the son of Cynvarch:—‘I too, have a son named Elffin,’ said Gwyddno, ‘be thou a bard and teacher to him, also, and I will give thee lands in free tenure.’ The terms were accepted; and for several successive years, he spent his time between the courts of Urien Rheged and Gwyddno... but after the territory of Gwyddno had become overwhelmed by the sea, Taliesin was invited by Emperor Arthur, to his court at Caerlleon upon Usk, where he became highly celebrated... It was from this account that Thomas, the son of Einion Offeiriad… formed his romance of Taliesin.”

...”Emperor Arthur”!?

This account had been published by Iolo Morganwg’s son, Taliesin Williams, (yes, you read that right – he named his son ‘Taliesin’,) in the ‘Iolo Manuscripts’ a year earlier, so it could be one of Iolo’s forgeries. However, Charlotte Guest also gives what seems to be a variation on the same story from another source. In any case, it is strikingly similar to the fictional ‘The Misfortunes Of Elphin’ by T. L. Peacock, as it gives a definite structure to the Hanes Taliesin and connects him to Arthur. It also supposedly brings together the legendary Taliesin with the ‘historical’ 6th century Taliesin, who supposedly wrote praise poetry for Urien Rheged. There’s also a curious echo of the Saint Patrick legend, who was similarly abducted by pirates and taken to Ireland… or so they say. It’s another contrived ridiculous story. Why would Taliesin , “The Great Bard,” go off fishing in the Irish Sea in a bloody coracle and even if he did, why didn’t he use his supernatural powers to deal with the pirates? Obviously, the intention is to unite the different versions of Taliesin’s legend and connect them both to “Emperor Arthur” using the familiar theme of St. Patrick’s kidnapping to add veracity.

As the nineteenth century advanced, British imperialists sought to accuse the natives of their colonies and internal peripheries, including Wales, as holding ‘unreasonable, uncivilized and unprogressive customs or tendencies’, thus justifying British intervention in those territories and cultures. The Welsh language suffered similar vilification.

From 1850, the notion that Taliesin embodied the transition between Paganism and Christianity gradually gained momentum. Somewhere along the line Druidism became entangled in the same argument and through Taliesin it gained a kind of acceptable evolution from Paganism to Christianity. We can see evidence of this in the likes of William Blake who was a devout Judaeo-Christian whilst at the same time claiming to be a Druid.

Druids at Stonehenge

Source

W. F. Skene published ‘Four Ancient Books Of Wales’ in 1868 which cast doubts upon the authenticity of the Hanes Taliesin, implying that the sources used by Guest and Pughe for their Mabinogion version, were forgeries by Iolo Morganwg, whose reputation was already in tatters by that time. It has since been demonstrated that Skene’s ‘Four Ancient Books Of Wales’ are themselves full of errors, however, at the time of publishing he was seen as a highly competent authority.

By the turn of the twentieth century the whole issue had gone full circle and was back to the 18th century “cart before the horse” belief whereby all of the Taliesin material conceals cryptic clues to forgotten history and the mysterious Druidic religion. However, Alfred Nutt, in his second volume of ‘The Voyage Of Bran’, compared the Gwion Bach section of the Hanes Taliesin to poems from 'Llyfr Taliesin' (The Book of Taliesin.) He concluded that some of the poems actually presuppose the Hanes Taliesin, and therefore it must have existed in some form before they were written. Whereas the existing manuscripts date from the fourteenth century, Alfred Nutt believes its basic elements may be much older still from a common ‘fund’ of Celtic tradition.

Later in the twentieth century emphasis turned away from the Hanes Taliesin and it all got even more complicated...

“Robert Graves (1895 – 1985) [claims], that there were three Taliesins--a god of poetry, a sixth century poet who served under King Urien of Rheged, and a thirteenth century who wrote what is known as the Llyfr Taliesin, a collection of the poetry of Taliesin 2 and Taliesin 3, with bardic fragments attributed to Taliesin 1.” Source

(Much of the above information is from ‘A Misfit Mythology: Hanes Taliesin In English Literature and Culture in the Nineteenth Century’ by Tyler S. Baxter, 2023.)

Patrick K. Ford translated the “Ystoria Taliesin” or History of (Hanes) Taliesin in his 1992 book of that name. He provided some valuable insights in his introduction to that work which I will summarise below. Of course, we have to realise that Patrick Ford incorporates the standard chronological assumptions in his evaluation of Taliesin’s place in history and scholarship, so we’ll just have to bear that in mind as we go along.

Our knowledge of Taliesin begins with Nennius and the ‘Historia Brittonum’. Nennius’ existence is even more dubious than that of Taliesin, as is his authorship of the book, which is supposedly dated to the beginning of the ninth century. Nennius himself was said to have been a Welsh monk who lived in the remote Powys region of Wales. As expected, the ‘Historia Brittonum’ delivers all the usual Roman and Anglo-Saxon invasion, conquest and subjugation stuff and Arthur is introduced, not as a king, but as ‘Dux Bellorum’. Taliesin is introduced as one of five poets ‘famed among the Welsh’ in the sixth century. King Ida of Northumbria was supposed to have been in power at that time, but surprisingly a certain Talhaearn (small dull forehead maybe?) was considered to have been the father of poetic inspiration (awen) with [A]neirin, Taliesin, Bluchbardd, and Cian making up the ‘famous five’. According to this Nennius, the period in question was a ‘golden age’ of the North British, allegedly being shortly after the ‘Age of Arthur’ and the dramatic events of the Roman withdrawal from Britain… here we go again – not the 6th century, but the 10th if any of it is true.

The famous five were considered to have been responsible for establishing the Welsh poetic tradition during this ‘golden age’, which again deciphers as there having been no Welsh poetic tradition prior to the 10th century cataclysm. As far as surviving material goes, a collection of poems called ‘Gododdin’ is ascribed to Aneirin and survives in a manuscript of the second half of the thirteenth century called the Book of Aneirin, some 700 years after the ‘golden age’ during which Aneirin was claimed to be around. Taliesin we know about already, but the others are extremely obscure. Talhaearn, supposedly the father of awen, gets a mention in the Welsh Triads and also in one of Taliesin’s poems along with Cian. Even so, the ‘famous five’ have been accepted as historical figures in Welsh scholarship. Furthermore, Merlin (Myrddin) and Llywarch Hen are often included as a sixth and a seventh. Obviously though, Merlin has a strong association with Arthur, which mucks up the establishment of the Welsh poetic tradition in the ‘golden age’ theory. These two interlopers are from Welsh literary sources outside of Nennius which only name Aneirin, Taliesin, Myrddin, and Llywarch Hen – not Nennius’ famous five… just a famous four.

(During my research I read somewhere that Talhaearn was said to have murdered Aneirin, but I’m afraid I can’t recall where it was. Sorry.)

Apart from all of the euhemerism, Christianisation, Romanisation and redefinition that went on in relation to this ‘Welsh poetic tradition’, there was another major factor involved. The arcane, metaphysical and supernatural content of poems and traditions regarding both Merlin and Taliesin, were just too much for the glossators. Instead, both were given split personalities – one ‘historical’ and one mythological.

Taliesin frequently appears in the Mabinogi, which is of course considered to be entirely mythological by scholarship – Welsh or otherwise. Interestingly, Taliesin is named as one of the three chief bards of the Isle of Britain. The other two are Merlin son of Morfryn and Merlin Emrys also known as Ambrosius. To be honest, I’m very wary of the Welsh Triads as I think I’ve probably said before, I don’t think they’re reliable either chronologically or factually and we’ve already seen how Iolo Morganwg created and embellished many of them. However, this does show that Merlin was also split in two: one a wild man of the woods, as per the Irish tradition of Mad Sweeney (Suibhne Geilte,) and the other as the ‘historical’ figure of Arthur’s protector and companion.

I wanted to put an image of Mad Sweeney here, but my internet search was inundated by some maniac from an American TV series called 'American Gods' or some such crap - he wasn't a bloody god and he certainly wasn't American, which shows exactly how we are manipulated these days. Sickening…

The original Irish tale of Mad Sweeney itself has even been split into two versions – one ‘mythological’ and the other supposedly historical involving a saint in the 7th century and then the same happened again in the 1400's… or is that yet another one of those duplicated and backdated events?

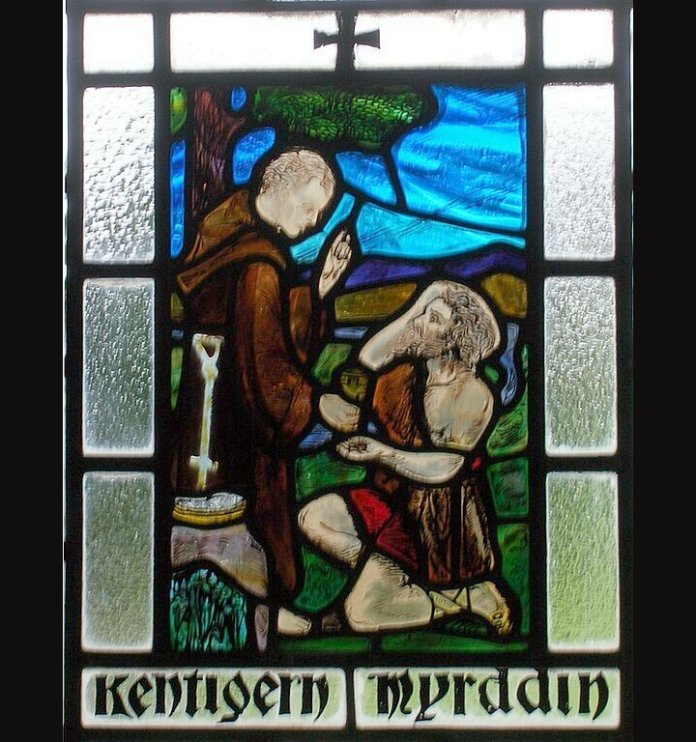

“...the late-15th-century Lailoken and Kentigern. In this narrative St. Kentigern meets a naked, hairy madman called Lailoken, said by some to be called Merlynum or Merlin.” Source

Merlin and Saint Kentigern

Public domain

Just to confuse matters further, even Romanisation gets involved. In a sixteenth century manuscript copy of one of Taliesin’s poems, there is an inscription in Latin which refers to Taliesin as ‘Ambrosius Taliesinus’. Nenniusinus also refers to Merlin as Ambrosius – which is of Greek derivation meaning ‘divine, immortal’. Let’s not forget that in the ‘History of Taliesin’ the poet himself claims that John the Baptist knew him as Merlin, which is frankly ridiculous, but indicative of something that was even widely discussed in the 1500s...

“...there are many opinions and much talk among people, for many of them hold the opinion and aver firmly that Merlin was a spirit in human form that had been in this shape from the time of Gwrtheyrn to the days of King Arthur, when he vanished. But then this spirit returned in the time of Maelgwn Gwynedd, at which time he was called Taliesin. It is said that he was living again in a city called Caer Sidia, whence he appeared a third time, in the days of Morfryn Frych, whose son he was said to be, and in this age he was called Merlin Wyllt, “Wild.” But in spite of all this, to this day he is said to be reposed in Caer Sidia, whence some people firmly believe he will rise up once more before Judgment Day. And indeed, I believe this story to be true, for it is widely known throughout Wales and in England too.” (Source: ‘Tales of Merlin, Arthur and The Magic Arts’, from the 16th century ‘Welsh Chronicle of the Six Ages of the World’, by Elis Gruffydd.)

We have come across this same ‘reincarnate gods’ idea before, when it was discussed in part two of ‘A Quest for The Lost Realm of Faërie’. We showed enough evidence to demonstrate that it was an intrinsic feature of pre-Christian belief, particularly among the so-called ‘Celts’. We also discussed the idea that most, if not all, of the main characters in what is today considered legend or mythology, were in fact Faë, that is they were from Annwn – the Otherworld, in just the same way as Taliesin/Merlin was described above (and in the poem ‘Preiddeu Annwfn’,) as being from and still surviving in Caer Sidia or Sidi – which is itself another name for the Otherworld.

I find it interesting that the Taliesin/Merlin/Merlin Wyllt figures have been merged into the embodiment of the spirit of poetry and ‘divine wisdom’, which in turn has come to be known as “Chief Bard.” It doesn’t fit at all with the Hanes Taliesin legend whereby Gwion Bach had to steal his divine wisdom and inspiration from Cerridwen's Cauldron in the Otherworld to become Taliesin, rather than simply inherit it from his previous incarnation. Also, whilst Taliesin does appear in the Mabinogi, it was Merlin who became associated with Arthur in all of the major Arthurian romances, not Taliesin, or are they all interchangeable?

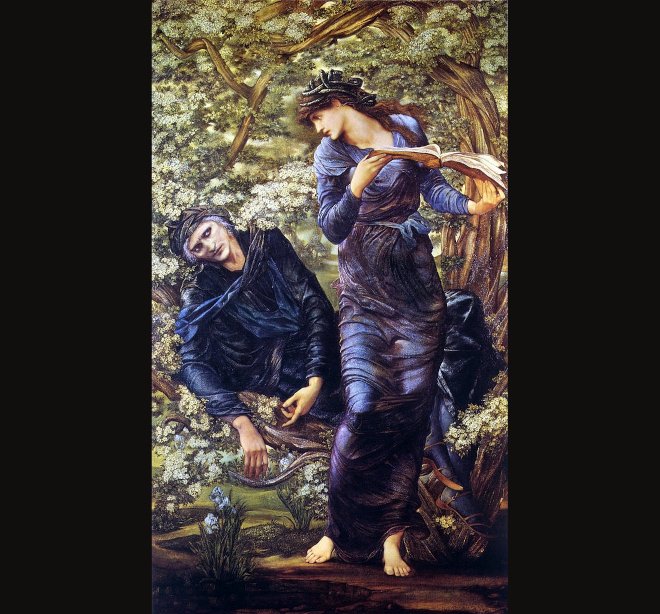

The Beguiling of Merlin

Edward Burne-Jones, 1873-1874

Public Domian

In a further attempt to bring some clarity to the whole Taliesin, Merlin, Iolo Morganwg, Druid situation, I want to take a closer look at what they call ’The Medieval Bardic Tradition’. Well, it wasn’t exclusively Welsh to start with, it was apparently a ‘Celtic’ British phenomena, BUT who do we have to thank for recording its presence in the British Isles over 2000 years ago – why the Romans of course!

The standard argument for justifying the antiquity of the Bardic tradition usually goes something along the lines of there being a requirement for keeping records regarding ancestral lineages, agreements, disagreements, bequests and accomplishments. This, of course, had to have been done orally, by someone who was specifically responsible for remembering it all. It’s also usually claimed that this was an important and highly specialised position within any society or group. Furthermore, the act of learning and recalling all of this information would be made much easier through the use of some kind of what’s now called Mnemonics. Therefore, it’s no surprise that the Bards stored and recalled the necessary information in the form of poems or ballads. It’s also claimed that as an art form, it naturally became associated with the Goddess – Brigid and or Cerridwen depending upon the locality, although even Bran the Blessed was given the title God of the Bards.

From this, it’s not difficult to imagine that the Bards became the celebrities of their day and of course, fame always brings its own responsibilities and pitfalls, not to mention someone who wants to organise and control everything. So, on the basis of the foregoing arguments, Bardism became an organised and authorised profession. However, is any of that true? Do we trust that there were Romans in the British Isles 2000 years ago or that Britain was even an island back then? In pre-cataclysm times, were people really as obsessed with keeping records as we are today? Were their memories and attention spans as bad as ours are now? Does any of the above make Bardism a religion? Were the Bards actually priests or just singer-songwriters?

The following is an excerpt from the Introduction to ‘Tales of Merlin, Arthur and the Magic Arts’. This book was written by Elis Gruffydd in the 16th century, who is also one of the original sources for the Hanes Taliesin. The Introduction is by Professor Jerry Hunter:

“Although the medieval bardic tradition continued throughout the sixteenth century, a very different kind of Welsh literati were challenging the bards’ time-honored cultural hegemony before the end of Elis’s life. In that tradition, professional poets underwent years of training before graduating into the upper echelons of the bardic order and being licensed to compose and perform strict-meter praise poetry for ‘uchelwyr’, (members of the Welsh gentry.) Bards often served as manuscript copyists as well and were thus guardians and transmitters of traditional Welsh letters and learning by multiple means. Now, however, university-educated humanists were an increasing cultural force, sometimes openly criticizing the traditional bards and debating ways in which the Welsh language and its literature could be developed and enriched, as well as ensuring the publication of the first Welsh books, in the 1540s. Elis did not attend university and so did not receive formal exposure to the studia humanitatis curriculum, and thus he cannot be described as a humanist in the strict sense. However, his work displays a commitment to what can be described more loosely as a humanist educational agenda. By the same token, he was not a bard, although he was certainly exposed to a great deal of bardic learning and compositions.” (Source: Tales of Merlin, Arthur and the Magic Arts, Elis Gruffydd, Intro by Professor Jerry Hunter)

So, Bardism was a medieval tradition whereby praise poetry was composed within a strictly controlled format and performed for ‘The Gentry’. Coincidentally, in English the word ‘druid’ started being kicked around in the 16th century. It seems to have originated in Irish mythology…

‘Old English had dry "magician," presumably from Old Irish drui. The Old Irish form was drui (dative and accusative druid; plural druad), yielding Modern Irish and Gaelic draoi, genitive druadh "magician, sorcerer."’ Source

Then it got all mixed up with Humanism and in what’s now called the Proto-Indo-European language cobblers and found its way into French, Latin and Gaulish where it became the label for ‘The Enemy’, because Christianity needed an identifiable enemy. Any ballads that had managed to survive Christianisation and retained their arcane and supernatural elements, could now be attributed to a specific group that could be demonised.

Modern Druidry claims that Taliesin called himself a Druid in his poem ‘Buarth Beirdd’...

“Wyf Dryw, wyf syw”

I am a Druid, I am a Sage

However, even the renowned Taliesin expert Marged Haycock translates ‘dryw’ as ‘wizard’, not druid...

“wyf dur, wyf dryw, wyf syw, wyf saer;

wyf sarff, wyf serch…”

I’m as hard as steel, I’m a wizard, I’m a sage, I’m a craftsman; I’m a serpent, I am desire…

Modern Druids still dispute this though, insisting that it can be found in …

“...the University of Wales Dictionary of the Welsh Language as an antiquated term to mean ‘derwydd’ (druid)” Source: ‘The Order Of Bards Ovates & Druids Mount Haemus Lecture For The Year 2012 - Magical Transformation in the Book of Taliesin and the Spoils of Annwn’, by Kristoffer Hughes (or perhaps originally from Iolo Morganwg.)

‘Derwydd’ sounds remarkably like the name that the witch Endora gave to Darren in the TV series Bewitched.

The etymology of the word bard itself dates from the mid 15th century, although it derives from Celtic (and Greek and Latin) where it meant "poet, singer," and "he who makes praises.” It wasn’t universally used as a title of respect either – in Scotland it was quite the opposite. It’s possible that as disseminators of these wicked and naughty stories, the Bards were were automatically associated with what became ‘Druidism’.

A more exotic view of poets and bards is provided by Patrick K. Ford in his 1992 book ‘Ystoria Taliesin’...

“Poets were at once flesh-and-blood persons who functioned in the courts of princes and kings, and divinely inspired (‘frenzied’) persons who behaved not at all like ordinary mortals and who travelled in the past and future and in domains forbidden to ordinary men. Like CÚ Chulainn, who was a docile and loving lad and protective husband, but who became a grotesque parody of human form capable of supernatural feats when he functioned as the divine hero, Taliesin/Merlin enjoyed both normal ‘historical’ life and the raptured existence of the supernatural.”

Cú Chulainn

Source

The problem with that is Cú Chulainn wasn’t a poet or a bard, he was a semi-divine hero capable of shape-shifting. I don’t think Merlin has left us many poems either, although there is one called ‘The Conversation between Myrddin and Taliesin’ and claims to be a poetic conversation between the two of them, which is “considered to be” written by Myrddin ...or Merlin. It’s found in the Black Book of Carmarthen, which dates from the mid 13th century. If it’s genuine, it makes mockery of the reincarnated Bards theory. Taliesin is the one mainly associated with poetry and he only ever managed any shape-shifting when he was Gwion Bach.

Where is it written that before the invention of organised religion, we as a species, required the intervention of a third party between ourselves and divine wisdom or inspiration? Nowhere – other than within organised religions. In rural areas of South America even today Shamans can be found around almost every corner. They don’t belong to any kind of organised body. They don’t claim to be ‘Druids’ or ‘Bards’, or to belong to any kind of priestly class. They are just ordinary people who are still in touch with something the rest of the world lost long ago. Of course they all have various specific talents, which are more often than not, hereditary, just as in Wales…

"Many parts of the Principality [Wales] had men and women who sold winds and weather to sailors. Modryb Sina (Aimt Sina) was one of the cunning women who could procure 'a fair wind or foul' for sailors and others who went to her haunts, Lavernock. Sully, and Cadoxton-juxta-Barry, in the eighteenth century. Ewythr Dewi (Uncle David) was prepared to do the same. He lived on Barry Island, and used to travel down to Swansea in the days before the great ports and trading places at Cardiff and Barry were known. Bill o'Breaksea accommodated people in the same way at the little harbour of Aberthaw, South Glamorgan. These kinds of people were to be met all along the coastline of North and South Waies. Mari, of Lleyn, in the North, and Modryb Dinah, of Sker, in the South, were experts. Whichever way these men or women turned their hats and wished, therefrom the desired wind would blow...On the Gower peninsula whole families were adepts in the art of storm-raising." (Source: ‘Folk-lore & Folk Stories of Wales,’ Marie Trevelyan, 1909)

This need for us to be shepherded like sheep is something that has been carefully cultivated within us since the cataclysm. Also, bards were for the flattery and entertainment of powerful men, not normal folk.

We have already seen that, there was a kind of ‘backlash’, whereby the Druidic enemy they had created and sent back into the past, suddenly manifested itself in the present. It occurred at a time when many people were looking to the past for a sense of identity and some kind of heritage (real or invented.) Druidism was tailor-made for this purpose and Iolo Morganwg’s role in that process should not be underestimated. It was during this ‘English Romanticism’ period that publication of the Hanes Taliesin encouraged the association of Taliesin in particular and bards in general, with Druidism. The fact that no one could make head nor tail of the secrets the poems revealed only served to make it all the more appealing – especially to ‘mystics’ whose main purpose seems to be to make a mystery of everything.

In a strange twist of fate (or not), all of the efforts to portray Paganism as misunderstood Judaism, actually backfired, or maybe they didn’t ...perhaps that was the plan all along. If we add to this Iolo Morganwg and his quest for a Welsh national identity, which in turn was based upon not only his own delusions, but also manuscripts with a dubious provenance, it’s not difficult to see how a new Abrahamic religion was born, a guilt-free hybrid Paganism that became Druidism… or maybe we should call it Jewidism?

Its confused manifestation can clearly be seen in the works of the previously mentioned William Blake. In fact, the hymn ‘And did those feet in ancient time’ has almost achieved the status of an alternative National Anthem in England…

“And did those feet in ancient time,

Walk upon England’s mountains green:

And was the holy Lamb of God,

On England’s pleasant pastures seen!

“And did the Countenance Divine,

Shine forth upon our clouded hills?

And was Jerusalem builded here,

Among these dark Satanic Mills?”

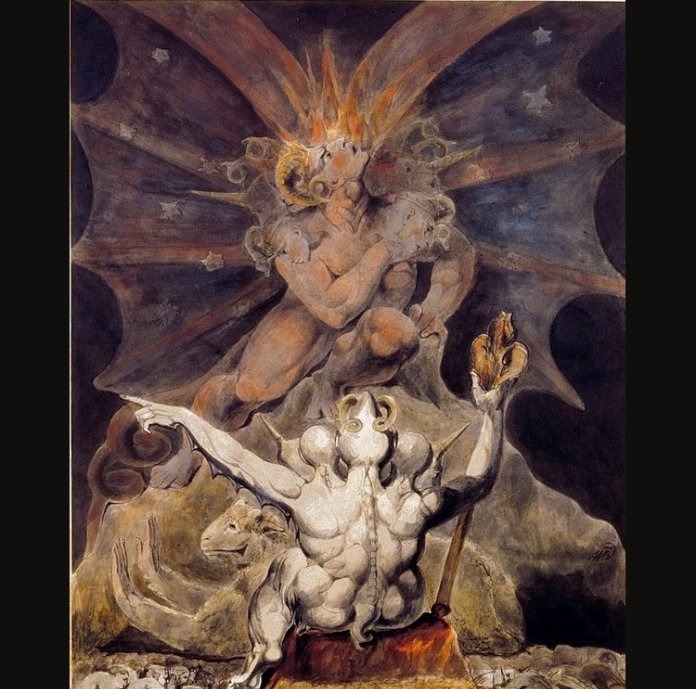

The Number of the Beast

William Blake, Public domain

Depending upon your religious persuasion, or gullibility, “those feet” either belonged to Joseph of Arimathea or Jesus himself, therefore the hymn could quite happily be sung in Christian Churches of all denominations. However, the original poem by William Blake is actually from the preface to his epic ‘Milton: A Poem in Two Books’, which is a very curious mixture of Judeo-Christianity and Paganism. Who knows, maybe “those feet” actually refer to Taliesin’s appendages?

I must apologise to any Druids who might be reading this. I don’t doubt that modern day Druids have the best of intentions and that much of their belief system is based upon ancient foundations, but those foundations have not come down to us intact, neither is Druidism per se any more ancient than the 16th century.

More recently in the 21st century we have a very different take on the subject of Taliesin from Lorna Smithers in her 2015 publication, ‘The Broken Cauldron’:

“Whilst Taliesin is venerated by Druids as the spirit of the Awen incarnate, slipping effortlessly between worlds and forms, little attention is paid to the cost his theft exacts on the land and its inhabitants...

“...This is paralleled in his later life. Taliesin shamelessly and sycophantically sings the praises of northern warlords in return for riches and mead as the Brythonic kingdoms fall. His reckless determination to steal, with King Arthur, the cauldron from the Head of Annwn results in the deaths of hundreds of men...

“...Taliesin epitomises all that is questionable and dislikeable about the Bardic Tradition. I would rather identify with Avagddu than with the thief who refuses to learn from his mistakes and whose selfish greed can only lead to the world’s end as Cerridwen swallows everything.”

“At the centre of ancient British mythology stands the cauldron; a symbol of inspiration, wisdom, rebirth, the womb of Ceridwen, Old Mother Universe. What happens when it lies shattered, the universe fragmented, the world out of kilter?”

I must admit, I do have a lot of sympathy with that opinion. His conceited, dishonest persona appears to be given free rein rather than glossed over and doesn’t seem to fit with the simultaneous image of a Christian evangelist. Unless the story was some kind of victory celebration, whereby defeat of the enemy had to be achieved by any means possible. Taliesin may well have been some kind of semi-divine being from the Otherworld, but not everything that comes from there is consequently benevolent and why did he need to steal his gift of divine inspiration and prophetic wisdom from Cerridwen? Surely his all powerful Christian 'Lord' should have provided it to him... More on that later.

The situation regarding the Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde separations of Taliesin, Merlin, Mad Sweeney, etc., appear to have taken place much later. They had to be completely reinvented in order to give them a convenient, official, chronological existence and the relevant arcane, supernatural exploits and abilities became either the power of Christian faith and divinity or they were simply thrown back in time and labelled ‘mythological fantasies’. This isn’t really any different to thousands of other ‘mythological’ figures who seem to have both Pagan and Christian attributes – like Arthur and his knights for example and most of the Mabinogi characters.

These divisions mirror the separation of humanity from nature and its own true nature, which happened at the time of the 10th century cataclysm. All of our innate natural abilities had to be separated from us and redefined as something apart, something evil, supernatural, mythical. The label ‘occult’ is precisely demonstrative of this, with its meaning of ‘hidden’. As happens so many times, the truth is the complete opposite; we have given away the key to all of our power and I don’t just mean the belief in it, but the knowledge of it.

Another major factor in the adulteration of any original literature that spoke of the supernatural, was the Protestant Reformation. This kicked off at the beginning of the 16th century and introduced a new, vicious, barbaric form of Christianity across Europe and resulted in centuries of conflict between Catholics and Protestants. Whereas Catholicism still retained a veiled undercurrent of co-opted Paganism, Protestantism was ruthless in its persecution of all things Pagan, as its basic tenets came straight from the the Old Testament, the Jewish Pentateuch with its angry ‘fire and brimstone’ God. This resulted in the century long Witch Trials that caused the deaths of untold thousands of mainly women, who were accused of witchcraft, tortured, sexually abused, humiliated, strangled and then burned at the stake.

Shakespeare's Wyrd Sisters by John Raphael Smith

Public domain CC0 1.0

The 10th century cataclysm wiped away an entire civilisation, one that has been so thoroughly expunged that we can now only catch glimpses of it in our dreams. It left a blank canvas for what was to follow, for what we have become today.

In an attempt to de-euhemerise the Hanes Taliesin, I decided to strip it down to it’s very basic elements and restore the Goddess Cerridwen to her rightful status and location. She was a major Celtic Triple-Goddess, just the same as Bridget, Brigid, Brigit, Breed, Britannia and in Scot Gaelic Bride, Bridie, and Breeshja. If you have been following these articles, you will now that Brigid became St. Bride thus retaining the echo of her former status as the bride of the Pagan Sacred Marriage. Brigid / Bride was also the Goddess of eloquence and poetry.

The Hanes Taliesin story was obviously highly significant, as it was allowed to slip through the net in its ‘Gwion strand’ form and retain its supernatural elements right up until the 18th century, therefore, it must have related to something that was extremely important and significant to Christianity. At the heart of the tale, we find the Mother Goddess, Cerridwen, tending her cauldron – the Cauldron of Life. This obviously didn’t take place in our Earthly realm, but in the Otherworld. The concoction of Awen, or divine inspiration, life itself, should have been business as usual for Cerridwen, so the addition of an ugly son to the plot could be seen as both a contrivance and an insult. Obviously, Cerridwen couldn’t be portrayed as giving life from her cauldron, as only God would be capable of that in Christian ideology so, there had to be a specific reason for the concoction of the potion. Perhaps Morfran/Afagddu was Cerridwen’s choice for incarnation as the next human embodiment of divine wisdom and inspiration, with his ugliness being simply a slur.

Cerridwen by Christopher Williams, Public domain

The details regarding the potion within the cauldron are highly significant, although they don’t seem to have been given any attention by ‘scholars’ over the centuries. It would be ludicrous to suppose that Cerridwen – either in her role as Goddess or her portrayal as a witch – would give the crucial three first drops to her son and then simply allow the remainder of the concoction to break out of the cauldron and poison the land. It would totally defeat the object of making her ugly son acceptable within society.

In the text of the tale the cauldron itself utters a cry after Gwion has stolen the 3 first drops and then it breaks. In my opinion, this shows that the cause of the spilling out of the poisonous part of the potion, was Gwion’s act of betrayal and theft. Had he not done this, then the cauldron would not have ruptured. Gwion Bach acted purely out of self-interest by desecrating the sacred process and stealing the gift of divine inspiration for himself.

Gwion Bach shatters the Cauldron

spilling the poison across the land

Source

The fact that the spilling of what is described, “as powerful a poison as there could be in the world” barely gets another mention, is curious. In the one instance where it is mentioned, it happens in a weirdly prophetic manner, namely the poisoning of the horses belonging to Gwyddno Garanir, Lord of Ceredigion and father of Elfin, who would find and name the infant Taliesin later in the story.

There is an even more curious turn of events related to this. In one of Lady Charlotte Guest’s short biographies on Taliesin, we read that after Taliesin had been serving Elfin and his father for several years, Gwyddno Garanhir’s lands became “overwhelmed by the sea” – in other words, they turned into a wasteland. It was at this point that Taliesin was invited to “Emperor Arthur’s” court.

In fact, Professor John Rhys in his ‘Studies in the Arthurian Legend’ of 1891, proposed that Gwyddno Garanhir was a parallel to The Fisher King. However, this was due to him having a weir used for catching salmon, rather than him being king of the land and therefore responsible for its well-being. As I demonstrated in ‘The Grail, The Cataclysm,The Wasteland and Our Lost Ancient Sovereignty’, if Gwyddno had broken his sacred contract with the land as a result of his dealings with Taliesin, then his kingdom turning into a wasteland would be the inevitable result – as happened to the Fisher King in the Arthurian tales.

So, the poisoning of the land that occurred when Gwion Bach’s theft caused the cauldron of Cerridwen to break, very much appears to have had a prophetic edge to it. Was it Gwion Bach/Taliesin himself who was “as powerful a poison as there could be in the world?”

“Eric Hamp has suggested an etymology for the name Gwion, which would make the name analogous to that of the Irish Fer Fv, the element gwi- being cognate with Irish fi ‘poison’ (L.uirus ‘plant, juice' and other I-E cognates in Hamp, ‘Varia II: Gwion and Fer Fi’ Érion, 29 [1978], 152-3). The suffix -on, implying divine status is well attested: Epona, Modron (Matrona), Mabon, etc. Thus the name would mean 'the divine poison (person)’, or in Professor Hamp's formulation, The Little Prototypic Poison/Concoction’. On the surface, this would seem to contradict the text, which has it that everything in the cauldron of Cerridwen but the three drops of wisdom were poison. However, Gwion as carrier of wisdom might himself be poisonous, just as the cauldron's contents, the medium or vehicle of the marvellous drops themselves were poisonous.” (Source: ‘Ystoria Taliesin’, Patrick K. Ford, 1992)

Can you believe this.

Anyway, back to the de-euhemerising... Right after the theft of the 3 drops from the cauldron, there is the shape-shifting chase. Over the centuries many have argued that this relates to metempsychosis – the transmigration of souls and reincarnation, which was thought to be a specific belief of the Druids. No doubt it has been a belief of modern Druids ever since they were invented, and this very shape-shifting chase may well be the source of that belief. However, shape-shifting features heavily throughout so-called Celtic mythology, where it’s never about the transmigration of souls, but purely a change of physical form. Cerridwen and her cauldron are the source of all life, in all its forms, not just human life. Therefore, it’s perfectly reasonable to assume that Gwion Bach achieved the ability to choose and change his form when he stole the 3 drops from the cauldron of life.

Gwion Bach, Shapeshifter Extraordinaire

Source

Cerridwen’s ‘immaculate conception’ of Gwion Bach as her unwanted unborn infant is extremely contrived. It suggests she had no idea what she was doing by eating the seed. Of course, for Gwion/Taliesin to truly do the Abrahamic God’s work, he would need to be free of ‘original sin’. In order to De-Euhemerise this, it’s simply a case of realising that effectively Gwion was incarnated in a physical body. This was no doubt part of the process he triggered when he stole the 3 drops that were originally intended for Morfran/Afagddu.

To Cerridwen, all life would be sacred. This is the only explanation necessary to account for the fact that she didn’t abort his incarnation or kill him once he was born. Then we get the old Moses in a basket cliché and, of course, he just has to be found by exactly the right person who can be used to further his ambitions, or his ‘God-given’ mission.

The third party voice that speaks through the infant upon hearing Elfin’s reaction to its remarkable forehead, is extremely sinister. The infant’s constant singing and promises of wealth and glory to come for Elfin and his father are utterly bizarre. All that’s missing is the infant producing a contract and saying “Sign here please in your own blood.”

The Taliesin figure certainly plays the role of a Christian prophet / evangelist throughout the remaining story of the Hanes Taliesin. He even claims to have been known to John the Baptist as Merlin and that he was present throughout the crucifixion and other significant biblical events.

In fact, the name Elphin or Elfin, is also a curious reference to the Faȅ – Elven or Elf. In the story, Elphin is just a normal character whom Taliesin is able to manipulate in whichever way he desires in order to achieve his own agenda. Elphin appears to act out of kindness when he rescues Gwion from the weir but, as soon as the infant is named ‘Taliesin‘, it begins manipulating him with promises of wealth and fame. Elphin is eventually morally corrupted by this, which leads him into conflict. It’s precisely this conflict that enables Taliesin to further his own ambitions by giving him access to increasingly powerful authority figures, who can then, in turn, be corrupted. First to fall was Gwyddno Garanhir, whose lands were turned into a wasteland. Presumably this was due to Taliesin turning him away from the ‘geasa’ he made with the Goddess and to Christianity. After this the story gets confused and perhaps King Maelgwn Gwynedd was the next to fall after Taliesin humiliated all of his bards by using an enchantment, thus claiming the title Chief of the Bards for himself. It could also have been Urien Rheged as well, depending upon which version of the tale, you read – that version is also the one that links Taliesin to ‘Emperor Arthur’. If Taliesin turned him as well, then we have a strong candidate for the cause of the cataclysm.

So was Gwion Bach the ‘Divine Poisoner’ who stole ‘Awen’ from the Goddess Cerridwen and who then, through her compassion, allowed him to be reborn as Taliesin? Did this ‘divine’ Taliesin then go on to poison and sabotage the established belief system, leaving a blank canvas in which to redefine Paganism and replace it with Christianity? The claim of scholars that Taliesin represented the transition from Paganism to Christianity was actually correct and it’s a wonder he was never made a saint. However, the Church prefers its saints to be portrayed as martyrs, not arrogant, thieving mass-murderers who have to steal their power from the Pagan Otherworld.

At the beginning of this article, I fully intended to examine the ‘Book of Taliesin’ in detail. However, to be perfectly honest, I can’t be bothered. I know it’s going to be full of ridiculous contradictions and ludicrous dichotomies. I also know I’ll spend ages trying to make sense out of all the nonsense when there clearly is none left to be found. So, I’m afraid it will have to be a cursory glance.

There were very few translations of ‘The Book of Taliesin’ into English available within the public domain. The most prominent was from a book we heard of a little earlier: W. F. Skene’s ‘The Four Ancient Books of Wales’ which were full of errors. There were more accurate translations of The Book of Taliesin in existence, but they were / are all in private hands.

“It's exact history is unknown; it passed through the hands of several collectors during the seventeenth century, until finally being bought by Robert Vaughan, who added it to his library in Hengwrt, and stayed there until it entered the hands of W. W. E. Wynne in Peniarth. It was then donated to the National Library of Wales." (Source: lost e-book, apologies.)

There he is again, the Man from H.E.N.G.W.R.T. Robert Vaughan, so there’s a red flag already. He is my personal choice for the unknown 13th century scholar who “wrote” the collection of the various assorted Taliesins' poetry with its unknown provenance. How do you write a collection, shouldn’t it be edited? Anyway, he obviously wasn’t writing in the 13th century though. The thing is, the poems in that collection were clearly not all written by the same ‘Taliesin’...

“The Book of Taliesin, the oldest surviving copy of his works (written about 700 years after his time), attributes to him a variety of poems, some on religious themes, some arcane verses that belong to Celtic mythological traditions and that are very difficult to decipher, and some that refer to known historical figures. Of this latter group, 12 have been identified as being the work of the 6th-century poet.” Source

“Known historical figures…” in other words, figures we want you to believe were real. “Twelve have been identified” – how the bloody hell did they do that? Maybe during a séance? What a complete mucking fuddle.

Marged Haycock in her ‘Legendary Poems from the Book of Taliesin’, classified the poems follows:

Merlin and Viviene

Public Domain

There are certain crossovers between the Hanes Taliesin and poems from The Book of Taliesin, for example, in the poem ‘The Hostile Conferderacy’ we find…

“A hen got hold of me

A red-clawed one, a crested enemy;

I spent nine nights

Residing in her womb.”

It’s interesting to see the Taliesin considered Cerridwen to have “got hold of” him rather than swallowed him. He also clearly defines her as his “enemy” and the “nine nights” rather messes up the already perverse chronology. Cerridwen’s Cauldron was revered as the womb of all life, which reinforces the theory that Gwion was actually incarnated after being “got hold of.”

Other sources of information regarding who Taliesin was, according to poems in the Book of Taliesin, are as follows:

“I was enchanted by Math,

Before I became immortal,

I was enchanted by Gwydyon

The great purifier of the Brython”

(‘The Battle of the Trees’)

Math was a great wizard, and brother to Dôn, he is named as the king of Gwynedd in the Mabinogi, and was both mentor to and punisher of his nephew Gwydion. The lineage of Dôn is claimed to be the equivalent of the Irish Tuatha de Danann, but this has become so confused over the centuries it’s by no means certain and the opposing lineage of Llyr could easily be the equivalent. Anyway, whatever the actuality, Gwydion was a very bad lot indeed.

“I have been in the battle of Godeu, with Lleu and Gwydion,

They changed the form of the elementary trees and sedges.

I have been with Bran in Ireland.

I saw when Morddwydtyllon [Bran] was killed.

Complete is my chair [seat] in Caer Siddi,

No one will be afflicted with disease or old age that may be in it.

Manawyddan and Pryderi know it.”

(‘Song Before the Sons of Llyr’)

“Math and Eunyd, skilful with the magic wand, freed the elements.

In the life of Gwydion and Amaethon, there was counsel.”

(‘The Death-Song of Aeddon’)

Amaethon was Gwydion’s brother.

There are also direct references to Taliesin in the Mabinogi. He is listed among the seven survivors of the Battle of Ireland; he is in the company of the Blessed Head of Bendigedfrân (Bran), in the story of "Branwen uerch Lyr".However, he never takes an active role in these stories, his name is simply “dropped,” which is strange considering his supposed status. It’s as if he’s simply an “extra” or some kind of observer.