If the concept that’s embodied by the Realm of Faërie was only native to one culture then it could easily be dismissed as an aberration. Having touched upon Norse mythology and the situation in Iceland, We would like to see if our quest would benefit from descriptions of encounters by other races with The Realm of Faërie. The comparisons with Greek mythology are well documented, so we won’t go into detail regarding those, but may use it as a reference.

● Universality ○ The Mouras and Mouros ○ Morris Dancing ○ The Basques ○ First‑footing ○ Onslaught of the Christian Scribes

● Ireland ○ The Sidhe and the Tuatha de Dannan ○ The Gentry ○ The Fomorians ○ St. Patrick’s Purgatory

● England and Wales ○ A Midsummer Night's Dream ○ King Arthur as a God ○ Arthur, Sun God or Guardian of the North? ○ The Missing Arthur ○ The Fae Arthurian Court ○ Le Conte de la Charrette ○ The French Mythology Factory ○ Lancelot ○ Culhwch and Olwen ○ The Brythonic Tuatha de Danann

● The Fae Worldwide ○ The Vedic Connection

“We are now prepared to hear about the Daoine Maithee, the ‘Good People’, as the Irish call their Sidhe (pronounced ‘She’) race; about the ‘People of Peace’, the ‘Still-Folk’ or the ‘Silent Moving Folk’, as the Scotch call their Sìth who live in green knolls and in the mountain fastnesses of the Highlands; about various Manx fairies; about the Tylwyth Teg, the ‘Fair-Family’ or ‘Fair-Folk’, as the Welsh people call their fairies; about Cornish Pixies; and about Fées (fairies), Corrigans... in Brittany.” ‘The Fairy-Faith in Celtic Countries’ by W. Y. Evans-Wentz, 1911.

It seems to me that ‘Fair-Family’ and ‘Fair-Folk’ are the favourite origin for the word ‘fairy’. Another Irish name for the Sidhe is ‘The Gentry’ which coincides with the name ‘Gentiles’ used by the inhabitants of northern Spain and the Basque country to describe exactly the same phenomena. In this instance ‘gentile’ does not mean ‘non-Jewish’, but courteous, kind, helpful, elegant, charming, pretty or fair.

Whilst researching and writing this article we have found ourselves constantly sidelined by new connections that then proceed to scream for attention. We have had to draw the line though and shelve the information for later articles, otherwise this one will never get finished and the underlying point of it will be lost.

Faeries Looking Through a Gothic Arch

John Anster Fitzgerald, c. 1860 Public domain

Throughout the area of the Iberian Peninsula that stretches from Northern Portugal, through Galicia and across Asturias, the Fae are known as Mouras (feminine) and Mouros (masculine.) Before we go any further it’s important to clear up a potential pitfall regarding these names.

As is well known, the Islamic Moors conquered parts of Spain (Moros in Spanish, Mouros in Portuguese, Mairu in Basque.) A great deal of misinformation has been created through the totally inappropriate association of the Fae Mouras and the Fae Mouros with the Islamic Moors. The one part of Spain that was never conquered by the Islamic Moors was precisely Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria and the Basque region. The words moro, mouro and mairu imply ‘foreign’ or ‘of a different race’ and do not apply specifically to Islamic Moors.

Morris Dancing

Tim Green from Bradford, CC BY 2.0

This confusion has led to some ridiculous and amusing theories. A prime example involves the very British pastime of Morris Dancing, which is now considered a joke in itself, but has an exceptionally long tradition in British folklore. In times past it was referred to with a variety of spellings, such as Maurice or Mourish Dancing and tradition held that it came to Britain from Spain. Therefore, the assumption was made that it originated with the Islamic Moors. It was even suggested that it was originally the Fandango. Yes, that’s right, the “Scaramouche Scaramouche will you do the Fandango?” one and also the “We skipped the light Fandango” one.

If anyone has witnessed these two dances, then they will appreciate the ludicrous juxtaposition. The more logical explanation is that the dance was actually Mourish Dancing, i.e. the dance of the Mouros.

During recent years an immense effort is being made by mainstream scholars, scientists and archaeologists to force the Basque culture into the Indo-European mould. This Mouros / Moors confusion is being exploited to attribute local traditional ‘Fairy Preserves', such as Ringforts and mounds, to the Moors of north Africa, which is utterly ludicrous.

In the book ‘Myths, Legends and Beliefs on Granite Caves’ by Costas Goberna, J. Bernardino, Otero Dacosta Tereixa and López Mosquera, the “os Mouros” are described as follows:

''Mythical people with singular features and behavior. They live in deserted places – old ruins that are said to be built by them – and in uninhabitable worlds – under the water, under the ground, inside the rocks. This is “Mourindade”. They are also known as Enchanted, Gentlemen [Gentry] and Gentile, and even French, Vikings, Celts. They are said to have supernatural powers. They are not visible unless they want to be. They control magic, are pagans, sleep during the day and can even eat people. They are skilled in building tunnels and underground palaces. They have a lot of gold; even their oxen and carts are golden. They themselves are enchanted treasures. On the other hand, their daily domestic activities such as tending cattle, farming and games, music and dancing are the same as those in Galician peasant society ...They have a parallel in traditions such as those of the Breton Korrigans, the Scotch Pictos, the Follets of the Catalan caves, etc.”

Arco d’os Mouros (Arch of the Fairies), part of an aqueduct in the Bosque Encantado de Aldán (Enchanted Forest of Aldán), Cangas de Morrazo, Pontevedra, Galcia.

Source

They were deemed responsible for the numerous dolmens and megalithic structures found throughout northern Spain. There is also a very mysterious species called ‘Mouros Encantados’, who have been described as giant warriors that fought impressive battles with all who tried to conquer the lands they protected. Source

In this instance the word ‘Encantados’ refers to spell casting and the use of magic. Here again we have a higher level of Fae with god-like powers. This is mirrored in the neighbouring Basque mythology where only the names differ and in both regions this higher rank of Fae are always worshipped upon the highest mountain peaks.

Monte Pindo the Galician Olympus

Source

The Basque language of Euskera is totally unrelated to any of the languages around the Basque region. Whilst their culture is labelled ‘Celtic’ their language is not derived from or related to any supposed celtic forms of language. Their culture also pre-dates that of the so-called Celts. We have heard various explanations for the origin of the word ‘Celt’. One suggests that it was invented by the Victorians. Another claims that it was a Roman ‘slang’ expression for anyone outside of the Roman Empire – similar to the Scottish expression ‘Sassenach’ which simply means ‘outsider’, but has come to mean ‘English’. It’s also claimed that it comes from the Greek word Gal which means milky white. There’s even a theory that it comes from Slavic. The origin of the Celts themselves is all mangled up inside dubious theories that took hold like wildfire as the result of racial motivations and agendas. First there was the Caucasian explanation (which is discussed in this article) and then that was followed by the Aryan Race palaver (which is discussed in another article here.) These two theories have somehow combined into the Indo-European category, which was originally meant to identify a group of languages, but now seems to refer to a cultural group since the recent immigration frenzy began.

A representation of Basque mythology, based on legends and rites.

Josugoni, CC BY-SA 4.0

The onslaught of Christianity hit the Basque people very hard. The seventeenth century siege by the Inquisition was one of that organisations bloodiest episodes: the trials of Logroño against the "The sect of the witches of Zugarramurdi" and that of Bayonne, in the French Basque Country. These events saw the interrogation of some 7,000 men, women, children and even priests. Even the corpses of those found guilty after having been tortured to death were exhumed and executed.

Amalur (Mother Earth) is the great Basque goddess. She represents the earth and provides all that is necessary to support life. She is believed to dwell deep in the Earth and offerings to here are made in caves as these are the doors to the interior of the earth.

Mari is the earthly ‘physical’ representation or avatar of Amalur who embodies the force of nature. The two are often confused and can be compared to Gaia and Sophia. Furthermore, please note the remarkable similarity between the names Mari and Mary.

A rock formation inside The Cave of Mari. (Note the Orbs)

Public domain

Basque mythology is rich in its variety of Fae. We find the equivalents of elves, goblins, nymphs and fairies by other names plus many more. Basajaun for example, is the equivalent of the Green Man who also gifted knowledge of agriculture, woodworking etc. to mankind. The Mamarro are house elves or brownies (like Dobby in Harry Potter) found in many different cultures. The Galtzagorriak or Red Trousers (because that’s what they wear,) are very much like the Irish Leprechauns.

Basajaun and Basaandere

Morburre, CC BY-SA 3.0

The Jentilak were giants who inhabited the high mountain areas, many peaks in the Pyrenees are dedicated to them. It’s claimed that they were forced to move away by the introduction of blacksmithing, until they disappeared totally. It’s very interesting that it wasn’t the presence of iron that was the problem, but the working of it by blacksmiths. However, it must be said that such claims cannot be totally trusted as being authentic due to the strong Christian gloss that has been heavily applied to all matters pertaining to the Fae.

For this reason it’s very easy to find nonsense like this example: “They were Gentiles, but one of them, Olentzero, knew about the coming of Jesus Christ and went to give the good news to all the inhabitants of his land; because with this birth, all the mythological creatures described above would disappear forever.” Source

Don’t forget, ‘Gentiles’ is the same as the Irish word ‘Gentry’ and refers to the Fae in a general sense rather than non-jewishness. So, this giant Olentzero, a fae himself, proceeded to imprison all of the “Gentiles” in a cave and then toddle off to tell everyone the “good news.” Further manipulation subsequently turned the imprisonment in the cave into burning them all alive in a charcoal burner. This then apparently established the ‘Christian’ tradition of bringing charcoal to poor children for Christmas and gifts to good ones throughout all of the Basque territories. Just what every poor kid wants for Christmas – carbonised fairies.

Olentzero

aiaraldea.com, CC BY-SA 2.0

Even today throughout all of Spain naughty children are threatened with the gift of a lump of coal for ‘Reyes’ – the traditional day for giving gifts in Spain – which occurs six days after Christmas. What’s more significant is the ‘first-footing’ tradition of Scotland (and the Isle of Man) which takes place on New Year’s day. This may be due to Christmas having been banned for 400 years in Scotland up until 1950, the original Yule celebration of the Winter Solstice was probably nearer to Christmas Day. Anyway, one of the traditional gifts that has to be given by the first-footer is a lump of coal. This represents the gift of warmth and comfort throughout the coming year NOT cremated fairies. This custom has echoes in both Greek and so-called Celtic traditions.

First-footing

Source

Now we will join the Spanish as they set sail to conquer Ireland… Eh? I hear you say and with good reason.

It’s necessary to be conscious that up to a certain point in time, all ‘history’ was transmitted orally, with each particular race being responsible for their own traditions. The Druidic Bards, for example, would train for twenty years to memorise and study the stories and history of their people. The dominance of Christianity, which occurred during the first century AD, changed all of that. Enclaves of monks and scribes and friars and bishops were established everywhere for the express purpose of gathering all of this oral history together, censoring it, (or even destroying and recreating it entirely) and then recomposing it in a form that was compatible with Christian dogma.

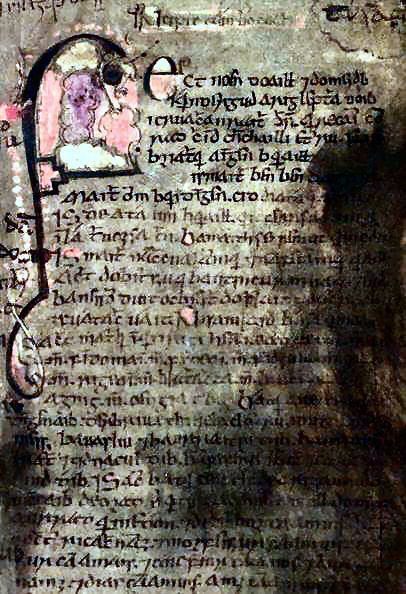

This is one of the greatest crimes ever, in our opinion, because the oral traditions were also intentionally silenced forever, meaning all we have left are mere shadows seen through a glass so heavily tinted with religious and political bias that it’s almost impossible to make anything out. One such example of this is the 12th century "Leabhar Gabhála" manuscript, known as the "The Book of the Taking of Ireland', written in Irish Gaelic and claiming to give the early history of Ireland. It claims to document all of the successive invasions that took place until the arrival of the ‘sons of a thousand from the kingdom of Breogán’, also known as ‘The Sons of Mil’ or actually - the Spanish.

The Bard, 1774

Thomas Jones, Public domain

An older source by another bunch of monks, scribes and some bishop or other, is the “Leabhar Laighneach” or The Book of Leinster. This confirms some of the material from the Book of the Taking of Ireland, but we’re only back as far as the 9th century. The assumption is then made that the information comes from the ‘original’ oral sources, which, of course, no one can either prove nor disprove.

Thomas F. O'Rahilly, a noted Irish scholar, claimed that the purpose of The Book of the Taking of Ireland was:

“firstly to unite the population by obliterating the memory of previous and different ethnic groups, secondly to weaken the influence of pre-Christian pagan religions by converting their gods into mere mortals, and thirdly to manufacture pedigrees into which the various dynastic groups could conveniently be fitted.”

Facsimile of folio 53 of the Book of Leinster.

Áed Ua Crimthainn et al, 12th century. Public domain

“From the beginning, LGE [The Book of the Taking of Ireland] proved to be an enormously popular and influential document, quickly acquiring canonical status. Older texts were altered to bring their narratives into closer accord with its version of history, and numerous new poems were written and inserted into it. Within a century of its compilation there existed a plethora of copies and revisions, with as many as 136 poems between them. Five recensions of LGE are now extant, surviving in more than a dozen medieval manuscripts.” Source

In fact, ‘The Book of the Taking of Ireland’ isn’t even a clever forgery. Either that or it was a rejected prototype of the Old Testament:

“The writers sought to create an epic written history comparable to that of the Israelites in the Old Testament of the Bible. This history was also intended to fit the Irish into Christian world-chronology and connect them to Adam. In doing so, it links them to events from the Old Testament and likens them to the Israelites. Ancestors of the Irish were described as enslaved in a foreign land, fleeing into exile, and wandering in the wilderness, or sighting the "Promised Land" from afar. The account also drew from the pagan myths of Gaelic Ireland but reinterpreted them in the light of Christian theology and historiography.” (ibid.)

The bit about sighting the Promised Land from afar was from the Spanish story, whereby some suitably biblical-like character claimed he could see Ireland all the way from La Coruña in Galicia. So, our voyage with the Spanish to invade Ireland has been cancelled due to lack of interest… I mean credibility. It really makes you wonder which are the real fairy-stories.

Due to the fact that pre-Christian Irish history has been replaced with an actual fairy-tale, it’s not my intention to waste my time, or yours, by dwelling upon it. Instead, I would like to attempt to allow the Irish to speak for themselves. In his book ‘The Fairy-Faith in Celtic Countries’ that W. Y. Evans-Wentz wrote in 1911, he used his position as an American diplomat to gather eye-witness testimonies from people in what he considered to be Celtic Countries.

Ossian on the Bank of the Lora, 1801. François Gérard

Public domain

“The People of the Goddess Dana, are the Tuatha De Danann of the ancient mythology of Ireland. The Goddess Dana, called in the genitive Danand, in middle Irish times was named Brigit. And this goddess Brigit of the pagan Celts has been supplanted by the Christian St. Brigit; ...to whom the wells and fountains have been re-dedicated, so to St. Brigit as a national saint has been transferred the pagan cult rendered to her predecessor. Thus even yet, as in the case of the minor divinities of their sacred fountains, the Irish people through their veneration for the good St. Brigit, render homage to the divine mother of the People who bear her name Dana,- who are the ever-living invisible Fairy-People of modern Ireland. For when ...the ancestors of the Irish people, came to Ireland they found the Tuatha De Danann in full possession of the country. The Tuatha De Danann then retired before the invaders, without, however, giving up their sacred Island. Assuming invisibility, with the power of at any time reappearing in a human-like form before [Irish people], the People of the Goddess Dana became and are the Fairy-Folk, the Sidhe of Irish mythology and romance. [Does this sound familiar?]

“Therefore it is that to-day Ireland contains two races,- a race visible which we call Celts, and a race invisible which we call Fairies. Between these two races there is constant intercourse even now ; for Irish seers say that they can behold the majestic, beautiful Sidhe, and according to them the Sidhe are a race quite distinct from our own, just as living and possibly more powerful. These Sidhe (who are the ‘ gentry ’ of the Ben Bulbin country and have kindred elsewhere in Ireland, Scotland, and probably in most other countries as well, such as the invisible races of the Yosemite Valley) have been described more or less accurately by our peasant seer-witnesses from County Sligo and from North and East Ireland. But there are other and probably more reliable seers in Ireland, men of greater education and greater psychical experience, who know and describe the Sidhe races as they really are, and who even sketch their likenesses. And to such seer Celts as these, Death is a passport to the world of the Sidhe, a world where there is eternal youth and never-ending joy, as we shall learn when we study it as the Celtic Otherworld...

The Valkyrie’s vigil ,Edward Robert Hughes (1851 – 1914)

Source

“...They (the Sidhe) are described as a race of majestic appearance and marvellous beauty, in form human, yet in nature divine. The highest order of them seems to be a race of beings evolved to a superhuman plane of existence, such as the ancients called gods; and with this opinion, strange as it may seem in this age, all the educated Irish seers with whom I have been privileged to talk agree, though they go further, and say that these highest Sidhe races still inhabiting Ireland are the ever-young, immortal divine race known to the ancient men of Erin as the Tuatha De Danann.

“Peasant and other Irish seers do not usually speak of the Sidhe as being little, but as being tall: an old schoolmaster in the West of Ireland described them to me from his own visions as tall beautiful people, and he used some Gaelic words, which I took as meaning that they were shining with every colour.” The Fairy-Faith in Celtic Countries’ that W. Y. Evans-Wentz, 1911.

“The gentry take a great interest in the affairs of men, and they always stand for justice and right. Any side they favour in our wars, that side wins. They favoured the Boers, and the Boers did get their rights. They told me they favoured the Japanese and not the Russians, because the Russians are tyrants.

“They frequently direct human warfare or nerve the arm of a great hero like Cuchulainn; and demons of the air, spirit hosts, and awful unseen creatures obey them. ...They are gods of light and good, able to control natural phenomena so as to make harvests come forth abundantly or not at all.

“The ‘Gentry’ Described. - In response to my wish, this description of the ‘gentry’ was given :- ‘The folk are the grandest I have ever seen. They are far superior to us, and that is why they are called the gentry. They are not a working class, but a military-aristocratic class, tall and noble-appearing. They are a distinct race between our own and that of spirits, as they have told me.

“Their sight is so penetrating that I think they could see through the earth. They have a silvery voice, quick and sweet. The music they play is most beautiful. They take the whole body and soul of young and intellectual people who are interesting, transmuting the body to a body like their own. I asked them once if they ever died, and they said, ‘No; we are always kept young.’ Once they take you and you taste food in their palace you cannot come back. You are changed to one of them, and live with them for ever. They are able to appear in different forms. One once appeared to me, and seemed only four feet high, and stoutly built. He said, ‘I am bigger than I appear to you now. We can make the old young, the big small, the small big.’ One of their women told all the secrets of my family. She said that my brother in Australia would travel much and suffer hard-ships, all of which came true; and foretold that my nephew, then about two years old, would become a great clergyman in America, and that is what he is now. Besides the gentry, who are a distinct class, there are bad spirits and ghosts, which are nothing like them. My mother once saw a leprechaun beside a bush hammering. He disappeared before she could get to him, but he also was unlike one of the gentry.” (ibid)

The Fomors (or The Power of Evil Abroad in the World,) John Duncan

Source

Assuming that the Christian scribes actually did retain some of the true ancient oral traditions of Ireland, then the Tuatha de Dannan’s habitual enemy was a race known as the Formorians. What follows is the typically confused mess that always results from the meddling of Christian scribes:

“The Fomorians are a race of supernatural giants in Irish mythology. In some accounts, the Fomorians are described as one of the earliest races to have invaded and settled in Ireland. The Fomorians are often described as monstrous, hideous-looking creatures. They were sometimes said to possess the power over certain natural phenomena, in particular destructive elements.

“In general, stories say the Fomorians took pleasure in waging war, and when they conquered other races, they would proceed to enslave them

“As a race of supernatural beings, the Fomorians are described as having the power to control certain forces of nature, notably the more destructive ones, including winter, crop-blight, and plague. The last of these is often mentioned in the texts as the means by which the Fomorians ultimately triumph over their enemies. During their invasion of Ireland, for instance, the Fomorians encountered the Partholons, [WS: allegedly] the first invaders of the island, and they are said to have fought many battles with them. After several years of fighting, the Fomorians succeeded in defeating the Partholons when they unleashed a plague upon them." (ibid)

We are grateful to stolenhistory.net member ‘Magnetic’ for the following information regarding the Geneva Plague of 1530:

“When the bubonic plague struck Geneva in 1530, everything was ready. They even opened a whole hospital for the plague victims. With doctors, paramedics and nurses. The traders contributed, the magistrate gave grants every month. The patients always gave money, and if one of them died alone, all the goods went to the hospital.

“But then a disaster happened: the plague was dying out, while the subsidies depended on the number of patients. There was no question of right and wrong for the Geneva hospital staff in 1530. If the plague produces money, then the plague is good. And then the doctors got organized.

“At first, they just poisoned patients to raise the mortality statistics, but they quickly realized that the statistics didn’t have to be just about mortality, but about mortality from plague. So they began to cut the boils from the bodies of the dead, dry them, grind them in a mortar and give them to other patients as medicine. Then they started dusting clothes, handkerchiefs and garters. But somehow the plague continued to abate. Apparently, the dried buboes didn’t work well. Doctors went into town and spread bubonic powder on door handles at night, selecting those homes where they could then profit. As an eyewitness wrote of these events, “this remained hidden for some time, but the devil is more concerned with increasing the number of sins than with hiding them.” François Bonivard, ‘Chronicles of Geneva’, second volume, pages 395 – 402.

“Following their defeat by the Tuatha Dé Danann during the Second Battle of Mag Tuired, the Fomorians lost their rule over Ireland, as well as their central role in Irish mythology. Nevertheless, legends say they were given the province of Connacht and were even allowed to marry some of the Tuatha Dé Danann.” Source

St. Patrick the Wizard

Source

It’s not possible to discuss the folklore and mythology of Ireland without mentioning St. Patrick. However, just as I was about to write this section Felix found that there is now much debate as to whether or not there were two St.Patricks. I looked into the claims and we decided it really isn’t important with regard to this article.

“When we come to the dawn of the Christian period in Ireland and in Scotland, we see Patrick and Columba, the first and greatest of the Gaelic missionaries, very extensively practising exorcism; and there is every reason to believe (though the data available on this point are somewhat unsatisfactory) that their wide practice of exorcism was quite as much a Christian adaptation of pre-Christian Celtic exorcism, such as the Druids practised, as it was a continuation of New Testament tradition. We may now present certain of the data which tend to verify this supposition, and by means of them we shall be led to realize how fundamentally such an animistic practice as exorcism must have shaped the Fairy-Faith of the Celts, both before and after the coming of Christianity.” ‘The Fairy-Faith in Celtic Countries’ by W. Y. Evans-Wentz, 1911.

The data is in the form of various folk tales whereby both Patrick and Columba are confronted by demonic forces that take possession of animals which they exorcise. According to Adamnan’s ‘Life of St. Columba’, the pagan Druidic custom of exorcising the milking vessel and also the milk obtained afterwards, was so ingrained that it passed on to their Christian descendants unchanged. Much of the ‘data’ is from these kind of domestic situations.

“Among the nine orders of the Irish ecclesiastical organization of Patrick’s time, one was composed of exorcists.” (ibid.)

In fact the fundamental importance of exorcism in the Christian religion is very much underestimated and also much less apparent in modern times. Even today though, Baptism is always preceded by an exorcism using holy water and the sign of the cross. In times past the ritual involved specially consecrated salt that was placed in the candidate’s mouth. The priest would use his own saliva to touch the ears and nostrils of the child and command the demons to depart.

The Baptism of Christ, Pietro Perugino (between 1480 and 1482)

Public domain

Let’s not forget that the Christian definition of a demon is anything that isn’t an angel, the Holy Ghost,or an apparition of the Virgin Mary and therefore includes all of the Fae, not just the demons. Once you are branded with the mark of Christianity it will act as a talisman against all of the Fae – just as it was intended to.

“And even after baptismal rites have expelled all possessing demons, precautions are necessary against a repossession : St. Augustine has said that exorcisms of precaution ought to be performed over every Christian daily; and it appears that faithful Roman Catholics who each day employ holy water in making the sign of the cross, and all Protestants who pray ‘ lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil ’, are employing such exorcisms.

“...And from all this direct testimony it seems to be clear that many of the chief practices of Christians are exorcisms, so that, like the religion of Zoroaster, the religion founded by Jesus has come to rest, at least in part, upon the basic recognition of an eternal warfare between good and bad spirits for the control of Man.

[Islam doesn’t seem to have an equivalent to baptism, although Judaism does and, of course, claims it to be the original uncorrupted form. It involves a full body immersion in ‘natural’ water for ‘spiritual purity’. Circumcision is a pre-requisite ...for men.]

“...The hold of the Tuatha De Danann on the Irish mind and spirit was so strong that even Christian transcribers of texts could not deny their existence as a nonhuman race of intelligent beings inhabiting Ireland, even though they frequently misrepresented them by placing them on the level of evil demons.” (ibid.)

The Irish Author, journalist and historian, Standish James O'Grady (1846 – 1928,) claimed that “...even the monks and Christianized bards never thought of denying them. They doubtless forbade the people to worship them, but to root out the belief in their existence was so impossible that they could not even dispossess their own minds of the conviction that the gods were real supernatural beings.”

“The earliest reference to this canon of spiritual beings comes from the Hymn of Fiacc, recorded in medieval manuscripts whose form of Old Irish is said to date them to between the 7th and 8thC CE. Fiacc was supposed to have been one of Patrick’s original 5thC CE apostles and the manuscript tradition comes from within the saint’s earliest establishments, so it can be considered of reasonable provenance. It states that, before the official coming of Christ to Ireland in the 5thC CE, the Irish worshipped beings called Sídhe:

“The Irish term ‘Sidhe’ (‘Shee’ or ‘Shee-the’) or it’s alternative Scots form ‘Sith’ (used by 17thC author Robert Kirk), and even its Manx form ‘Shee’, have survived down into more modern times associated with meanings congruent either with fairies, their speculative habitations (small hills or ‘sidhe mounds’), or their status, which in the case of the dead, meant a state of ‘peace’ entirely congruent with the dis-attachment to worldly things upon which the eastern definition of Siddha seems to depend.

“The Gaelic Sidhe were believed to be providential spirits who interacted with the human world but enjoyed a purely spiritual existence. They were sometimes seen as forebears – forerunners whose skill had ensured the wellbeing of the contemporary peoples. Like the Siddhas they were venerated as those who were spiritually ‘perfect’ and were believed – as ancestral spirits – to look after the needs of their subsequent relatives, hence the ‘hearth cult’ and ‘fairy faith’.” Source

In ‘The Colloquy with the Ancients’, part of the Silva Gadelica – another medieval Christianised version of Irish history – St. Patrick has conjured up the spirit of a certain long-dead warrior known as Caeilte so that he might question him about the history of ancient Ireland. An extremely unchristian thing to do. Caeilte appears as an ancient and withered old man. During the proceedings a beautiful young girl appeared named Scothniamh or “Flower-lustre”, daughter of the Daghda’s son Bodhb derg. Caeilte did not recognise her, but she was once his fiancé. Patrick was mystified by their difference in appearance and remarked upon it, to which Caeilte replied ‘Which is no wonder at all, for no people of one generation or of one time are we: she is of the Tuatha Dé Danann, who are unfading and whose duration is perennial I am of the sons of Milesius, that are perishable and fade away.’ [Although, please note, the sons of Milesius were a Christian invention.]

What all this points to is that the early Christian missionaries, like Patrick, were primarily infiltrators. Once they had become just as skilled as the Druids in pagan rites, magical practices and exorcism – i.e. they could connect and communicate with and command other entities in the Realm of Faërie - they then set about undermining, demonising and replacing their teachers. In effect they simply continued the existing paganism, but in the name of Jesus Christ. The mother of the Tuatha de Danann, the goddess Dana or Mari in the Basque tradition, was replaced by the The Virgin Mary, while Jesus, the apostoles, saints and angels replaced the Tuatha de Danann and the Sidhe themselves. The spiritual sovereignty over sacred wells, springs and rivers was obviously considered too demeaning for Mary, so Saint Brigit and various other saints were assigned to replace Dana / Mari in these minor roles.

This is why Roman Catholicism features The Virgin Mary so prominently, because they needed a goddess figure to supplant the one that was at the core of all the pagan belief systems. Even the Greeks had Hera as Queen of the gods, who passed into the Roman pantheon as Juno, but Christianity, Judaism and Islam are all purely patriarchal. The Virgin Mary is there solely to fill the gap left by the celibate gods of the Abrahamic religions, but she is not a goddess. In the pre-Islamic Arabian peninsula Al-Lat was worshipped as the chief goddess and some hypothesise that Allah was her consort before he presumably did away with her completely, or rather the marketing of Islam linked Allah to Al-Lat to ensure an easier take-over.

From the same ‘Colloquy with the Ancients’ we hear that Patrick’s mission was “to sow faith and piety, to banish devils and wizards out of Ireland; to raise up saints and righteous, to erect crosses, station-stones, and altars; also to overthrow idols and goblin images, and the whole art of sorcery.” Silva Gadelica.

The Hill of Tara, as seen from the air.

Alison Cassidy, CC BY-SA 4.0

The accounts of the final confrontation between St. Patrick and the pagan belief system in Ireland are fanciful and of course, written by the victors – the Christians. Tara was the symbolic heart of Ireland and the home of a hundred kings. The obvious supernatural dueling between the sorcerers (and I include Patrick in that) is portrayed as God’s miracles against the evil magic of the Druids, which resulted in God annihilating many thousands of non-believers.

Even though Patrick is accredited with driving all the ‘serpents’ into the sea – even though there were no serpents in Ireland – (but, we will see later that this word can also mean sorcerers) the subsequent rulers did not abandon their pagan beliefs or institutions for some time after the battle at Tara. However, in 565 AD, following a conflict between the power of the church against that of the king, the Christian officials placed a curse upon Tara. Yes, you heard it right – the Christian saints used exactly the same technique of cursing for which the Inquisition would later burn witches. Many, to this day, see this as having been a fatal blow to the unity and power of Ireland. A High-King ruling in Tara represented a hope for consolidation into one great nation, but when Tara was abandoned, so was that hope.

19th c. plan of the Hill of Tara based on a survey of the site and historical records.

William Frederick Wakeman, d. 1900. Public domain, click to enlarge

“Not until Christianity gained its psychic triumph at Tara, through the magic of Patrick prevailing against the magic of the Druids - who seem to have stood at that time as mediators between the People of the Goddess Dana and the pagan Irish - did the Tuatha De Danann lose their immortal youthfulness in the eyes of mortals and become subject to death. In the most ancient manuscripts of Ireland the pre-Christian doctrine of the immortality of the divine race ‘persisted intact and without restraint’.” ‘The Fairy-Faith in Celtic Countries’ by W. Y. Evans-Wentz, 1911.

However, once the monks, the friars, the bishops and their scribes got hands on the oldest manuscripts, then everything changed. The Tuatha de Danann became mere mortals.

Archaeological dig in the 1950s of Mound of the Hostages, Tara or Fourknocks passage tomb.

Family photo, CC BY-SA 4.0

One cannot help but wonder why the Tuatha de Danann, given that they were a god-like race, didn’t do what we have come to expect from gods in general and give Patrick and his gang a good Old Testament style smiting. This apparent pacifism and non-aggressive outlook (at least towards humans) ties in with the ‘Albans’ and other conquered and colonised inhabitants discussed earlier, who simply vanished from human sight rather than indulge in violent conflict. Of course, there will be those who claim it proves that they didn’t exist in the first place.

It isn’t necessary to go into too much detail regarding this, but it is another example of how interaction with the Realm of Faërie has been assimilated into Christian dogma. This particular rite is comparable to Virgil’s account of the Trojan Aeneas on his initiatory journey to Hades and was practised at Finn Mac Coul’s Lake, later called Lough Derg, Ireland. This was a sacred site in pre-Chrisitan times and in particular the cave upon what is now called Saint’s Island wherein the rite was performed.

1513 Map of Ireland of the Argentine Ptolemy, showing St. Patrick’s Purgatory and the Isle of Brazil.

Unknown author Public domain, click to enlarge

“During the seventeenth century, the English government, acting through its Dublin representatives, ordered this original Cave or Purgatory to be demolished; and with the temporary suppression of the ceremonies which resulted and the consequent abandonment of the island, the Cave, which may have been filled up, has been lost.” (ibid.)

Since that time a new chapel, appropriately called the ‘Prison Chapel’, has been erected on Station Island. Many thousands of pilgrims visit this site annually in order to clean away the accumulation of a lifetime’s sin through St. Patrick’s Purgatory which, as you might imagine, bears little or no resemblance to the original purpose of the ritual. Also any additional effect created by the specific location of the original cave is totally absent.

At first glance it may seem as if there is no comparison in English or Welsh mythology to the Tuatha de Danann of Ireland. That may well prove to be an illusion, however. As has already been stated, the Christianisation of Irish mythology required the Sidhe to be redefined as mere mortals rather than the beings from the Realm of Faërie that they really were. The exact same process has taken place in English and Welsh history.

It’s a sad fact that the remnants of England’s ancient history pale in comparison to those from the Welsh. The folklore shows a similar disparity between the two regions. It’s as if the Christian broom swept cleaner in England than it did in Wales. The literature is another matter entirely though. The earliest legends and mythology of Britain have been very clinically defined as ‘The Matter of Britain’ alongside ‘The Matter of France and ‘The Matter of Rome’. These three ‘Matters’ were first defined by a French poet called Jean Bodel in a poem about Charlemagne battling the Saxons that he wrote in the 1100’s:

"Not but with three matters no man should attend:

Of France, and of Britain, and of Rome the grand."

This is translated from French, which is probably why, to me, it sounds like utter nonsense. ‘Not’ ‘but’ and ‘with’ don’t belong together in any sentence. The original French doesn’t help much either, but I think the gist is, ‘there are only three matters that any man should attend to: blah, blah, blah.’

Exactly why that one line from that one poem should have such a huge significance attached to it is beyond me. Scholars, who of course know everything, tell us that it was all done to give the British a sense of identity and a feeling of significance in the world, which they lacked due to the cultural chaos created by the Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, Roman and Norse invasions. How considerate. They don’t offer the same explanation for the other ‘Matters’ as obviously the French and Italians didn’t require a sense of identity or significance as much as the poor, insignificant ...who were they again?

If this was true then that explanation is a possibility. If it’s not true and there’s no archaeology to support any of it, if the ‘Celts’ were an invention, if the Angles, Saxons and Norse were invited or part of ‘Greater Albion’ or Ancient Hellenland, if the Romans were the Normans then what is all this about? Why belittle and suppress pre-Christian Britain? It reminds me of the Shakespearean quote from Hamlet, “The lady doth protest too much, methinks.”

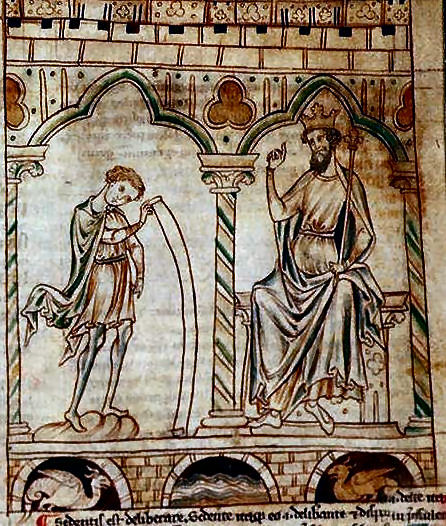

Merlin reads his prophecies to King Vortigern, from Godfrey of Monmouth's Prophetia Merlini. Illustration from the manuscript. Probably London, 1250 or earlier. Public domain

The Matter of Britain is largely taken up with the Arthurian cycle. Sounds like a ‘Tour de Britain’ bicycle race. This in turn is split into the Vulgate and Post-Vulgate cycles. To make matters more confusing, these cyles overlap, but generally cover the period from the 12th century to the 14th. Basically, The Matter of Britain began when the bloody monks, friars, scribes and bishops interfered with the legends, but it also includes some later anonymous sources. The Vulgate cycle is when some Norman / French poets interfered with them and the Post-Vulgate cycle is when Norman / French and German poets twisted Arthur and his Knights into Christian heroes of the Holy Grail and the quasi-mystical Rosicrucian movement. Everything since then has been an accumulation of those three cycles, except for Marion Zimmer Bradley’s ‘Mists of Avalon’ which was a degenerate perversion.

The burning issue this presents is how the flipping heck do you separate what’s original from what’s been added? There are claims that additional sources were discovered throughout this period, as we shall see. If we dismiss all of this on the basis that there are no primary sources, then that leaves nothing at all. We have decided to judge each piece of information on its merit and whether it’s furthering any particular agenda.

Titania and Bottom, c. 1790, Henry Fuseli

Public domain

“There is a Welsh tradition to the effect that Shakspeare received his knowledge of the Cambrian fairies from his friend Richard Price, son of Sir John Price, of the priory of Brecon. It is even claimed that Cwm Pwca, or Puck Valley, a part of the romantic glen of the Clydach, in Breconshire, is the original scene of the Midsummer Night's Dream. According to a letter written by the poet Campbell to Mrs. Fletcher, in 1833, and published in her Autobiography, it was thought Shakspeare went in person to see this magic valley. ‘It is no later than yesterday,' wrote Campbell, ‘that I discovered a probability — almost near a certainty — that Shakespeare visited friends in the very town (Brecon in Wales) where Mrs. Siddons was born, and that he there found in a neighbouring glen, called The Valley of Fairy Puck, the principal machinery of his Midsummer Night's Dream." Welsh Folklore, Fairy Mythology, Legends And Traditions, by Wirt Sikes, 1880.

Prince Arthur and the Fairy Queen, circa 1788

Henry Fuseli Public domain

A twelfth century Welsh poem from ‘Four Ancient Books’ published in 1868, describes the heroics of Prince Geraint and his men, who are referred to as “the men of Arthur.” Now, whichever time period you think King Arthur belonged to, or even if you think there were more than one King Arthur or none, the twelfth century was not the place for men of Arthur.

Whether Arthur was fact or fiction, he was most definitely a national hero, therefore the above description is both a compliment to Prince Geraint and his men as well as testament to King Arthur’s continuing esteem in the 1100’s. On the one hand we have the assertions of scholarly historians that Arthur was a living person – either one of two vaguely recognisable characters from around the mid first century and on the other hand we have the mythology that surrounds him and portrays him in an identical manner to any other pre-Christian divine being from the Realm of Faërie. The latter possibility offers another explanation to the description of Geraint’s men. In the Irish tradition of Badb, the war-goddess, she would direct and inspire her warrior devotees rather than take part in the battle herself. Therefore, if King Arthur was also a god-like being then the description “men of Arthur” could indicate the same arrangement.

The question of which came first, the actual person or the god is addressed by J.R.R Tolkien when he considers the same conundrum in relation to Thor, the Norse god of thunder.

“...if we inquire: Which came first, nature-allegories about personalized thunder in the mountains, splitting rocks and trees; or stories about an irascible, not very clever, redbeard farmer, of a strength beyond common measure, a person (in all but mere stature)...? To a picture of such a man Thórr may be held to have “dwindled,” or from it the god may be held to have been enlarged. But I doubt whether either view is right—not by itself, not if you insist that one of these things must precede the other.” ‘On Fairy Stories’ by J. R. R. Tolkien, 1939.

In the case of King Arthur, though, we are not dealing with a personification of a natural force, but, if we consider him to be a god of war, then of what exactly would that be a personification? The evidence so far indicates an ongoing battle between good and evil within the Realm of Faërie, as seen in the ongoing supernatural struggle between Tuatha de Danann and its counterpart, the Fomorians. Perhaps then this persistent struggle is the result of the natural forces of good and evil – in a purely dualistic sense.

That would make King Arthur a personification of ‘good’. However, that association would have to be made by humans. King Arthur can only have been associated with ‘good’ by people who were inspired by his actions to recognise him as ‘good’. Of course, Arthur was considered more than simply ‘good’, he encompassed wisdom, bravery, loyalty, respect, equity, kindness, etc. and could call upon supernatural power, in fact all one would expect from a hero / god.

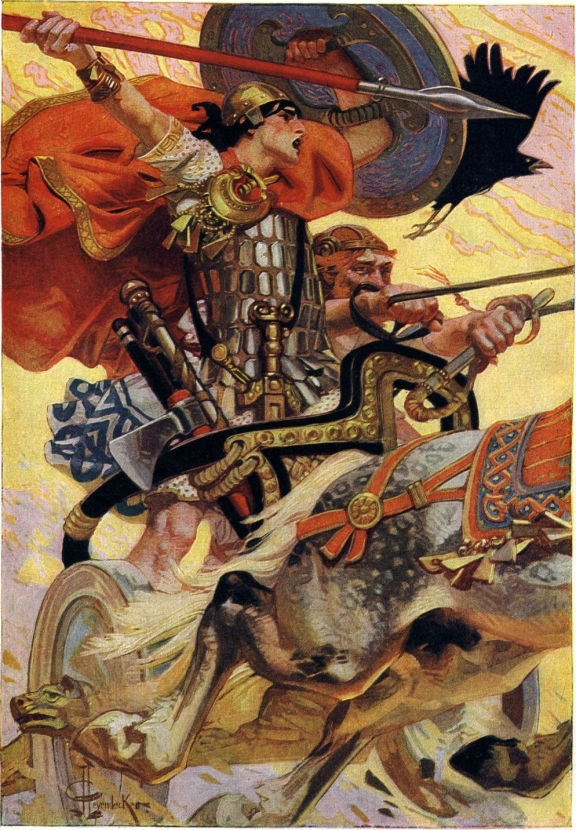

Cuchulain in Battle, Joseph Christian Leyendecker, 1911

Public domain

In the Irish tradition we have Cuchulainn, who was the son of the Tuatha de Danann god Lug and therefore himself a god incarnate in a human body. His story was similar to Arthur’s and his mission was to educate the race of men. To accomplish this he was in conscious communion with the invisible gods of the Faërie Realm throughout his life.

This concept of a god incarnate shouldn’t surprise us, after all according to the Christian Doctrine of Incarnation, Jesus is ‘fully God and fully human’. The Aztecs and the Peruvians believed that great heroes dwell in the sun from whence they reincarnate in times of need to teach mankind. A similar philosophy existed among the Egyptians and other peoples of the Old World, including the so-called ‘Celts’.

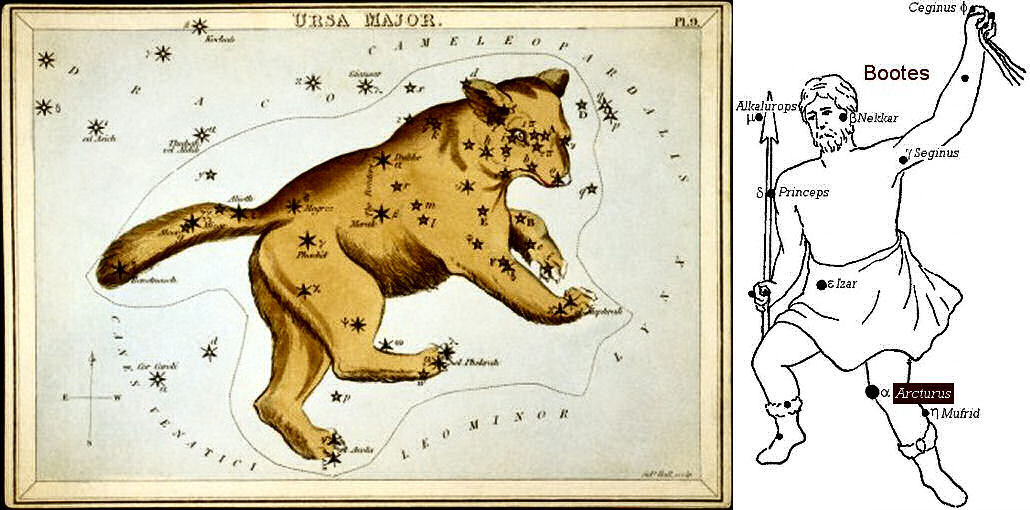

The idea of Arthur as a sun god has become quite popular these days, neither Felix nor I realised this until we started checking research for this piece. In our previous article, ‘King Arthur in Hyperborea & the Arctic Cataclysm’, we noted how Arthur has long been associated with Arcturus, 4th brightest star in the heavens and located in the northern constellation of Bootes. The name Arcturus translates as“Bear Watcher” or “Guardian of the Bear,” referring to the bear represented by the neighbouring constellation Ursa Major (the Plough or Big Dipper).” Source. These two constellations perpetually circle the North Pole or Arctic – which derives from the Greek words ἀρκτικός (arktikos), "near the Bear, or Northern" and ἄρκτος (arktos), meaning bear. Arthur has long been associated with both Arcturus and also the Bear, so this idea of him as a sun god comes as a surprise.

Ursa Major, The Bear and Arcturus. Johann Bayer

Public domain

Incidentally, a Big Dipper is a fairground ride that carries people up and down steep slopes on a narrow railway at high speed. It’s also known as a Roller Coaster. This seems to suggest that astronomy in North America is a strange and possibly recent thing.

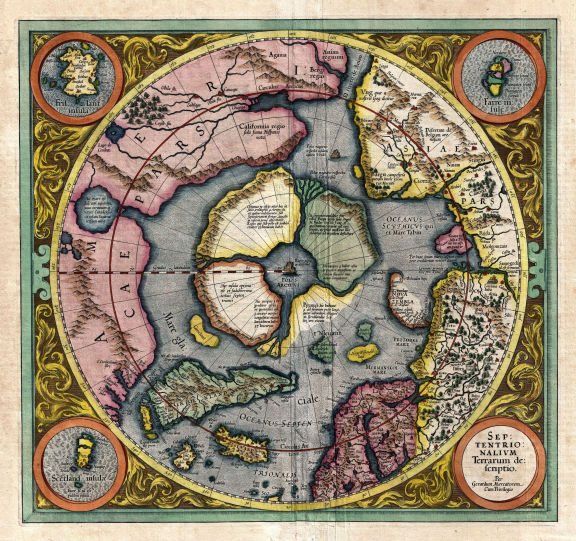

Dr. John Dee and Gerardus Mercator, both mentioned previously and featured in our earlier King Arthur article, referred to the area of the North Pole and the islands surrounding it as the Septentrional regions or islands. This terminology can also be found in other Arthurian texts. The name refers not only to the land, but also to the pattern made by the stars above it.

1606 Mercator Map of the Septentrional Isles

Public domain

According to the ancient Greek legend, Zeus fathered a child named Arcas by a nymph known as Callisto. Zeus’ wife, the Goddess Hera, was none too pleased about it and so turned Callisto into a bear …as anybody would under the circumstances. Some years later, Arcas, who had become the king of Arcadia and introduced agriculture to the area, unwittingly almost killed Callisto whilst hunting. Fortunately, Zeus prevented the catastrophe at the last moment and then reunited mother and son in the heavens above the North Pole. Callisto became the constellation Ursa Major (The Great Bear) or Arktos in Greek, whilst Arcas became the shining star Arktouros, or the “Bear Guardian,” with the task of watching over his mother, who is seen as the guardian of the North and of the Arctic Pole in particular. The association of the seven stars forming The Plough, or Arthur’s Wain or Wagon, (Bootes) correlate to Arcas as a teacher of agriculture.

The entire constellation of Bootes or Ursa Major, was generally referred to as Arcturus “from at least the eleventh century onwards, it was regularly spelled: Arturus, Arthurus, Artur, and even, once, Arthur. This was, of course, at a time when there were no exact rules for spelling, and names in particular changed dramatically from text to text, but what is more interesting here is the fact that this also happened in reverse—the name Arthur is regularly spelled Arcturus in a number of medieval manuscripts.” ‘Arthurian Magic’ by John & Caitlín Matthews, 2017.

If you add Latin into the equation – always a guarantee of complicating matters even further – you get ‘arth’ meaning bear and ‘uthar’ meaning guardian. Uther or Uthr was Arthur’s father and also guardian of the Otherworld – a place that will be discussed more fully later, but that is clearly within the Realm of Faërie. The Arctic association with the Otherworld or Underworld goes back a very long way. As well as being considered the cradle and origin of civilisation, it was also seen as a place of returning. Its title of the Land of the Dead is misleading to our modern world-view, but it should be understood as a joyful return to The Otherworld, the source, the Cauldron of Life.

Arthur’s association with The Great Bear goes as far back as the tenth century. Isidore of Seville and John of Sacrabosco both cataloged the constellation under Arthurus, Arturus and Arthus, names also given to Arthur throughout the medieval period.

The Arcturus association also features in John Lydgate's ‘Troy Book’ which dates from sometime between 1412 to 1420 and depicts Arthur / Arcturus as the wagonmaster of the Plough (Ursa Major) constellation. Also, in the pre-Roman British or ‘Brythonic’ tongue, Arthur translates as ‘Arth’, Bear and ‘ur’ man. Weirdly the Latin ‘Artorius’ also means ploughman.

Let’s not forget what we asked you to bear in mind earlier - the ‘Finnar’ or Saami, who were the Norwegian equivalent of Irish Tuatha De Danann, their favourite form to shapeshift into was that of a bear.

W. Y. Evans-Wentz makes no mention of the Arcturus connection, but does highlight the sun god claim in his 1911 book, ‘The Fairy-Faith in Celtic Countries’ (the one that we have been quoting from extensively,):

“...anciently among the Gaels and Brythons such heroes as Cuchulainn and Arthur were also considered reincarnate sun-divinities. As a being related to the sun, as a sun-god, Arthur is like Osiris, the Great Being, who with his brotherhood of great heroes and god-companions enters daily the underworld or Hades to battle against the demons and forces of evil, even as the Tuatha De Danann battled against the Fomors.”

William Price of Llantrisant, in druidic costume, with goats by A C Hemming, 1918

(CC BY-NC 4.0)

As far as we have been able to discover, the concept of Arthur as a sun god, comes from the late Victorian ‘Druid Revival’ period, in particular a book called ‘Light of Britannia’, published in 1893 and written by Owen Morgan. Once again, the theory revolves (literally) around the North Pole with the circular path of Ursa Major being referred to as the Round Table of Arthur and it further claims that the Druidic names also denote an entire farmyard and a harp in the northern sky all belonging to Arthur. How does this relate to Arthur as a sun god, I hear you ask? Well, again it’s claimed that ‘Arthur’ is one of the Druidic titles of the sun as a husbandman or gardener. Far be it from me, or Felix, to argue with these exalted opinions, but a Druidic language suddenly comes to light in the 19th century? Really? Anyway, the ‘Celts’ already had a sun-god who’s name was Gweir or Gwair (Lugh/Lug/Luga in the Irish tradition.)

“The name ‘Arthur’ started cropping up among late-sixth-century and seventh-century Irish migrants to Wales and Scotland. That people would suddenly start naming sons ‘Arthur’ and literature recording ‘although he was no Arthur’ (the reference to Arthur in ‘Y Gododdin’, ca. 600), indicates that the name Arthur had become fairly common by this time.” Source

A great deal has been made regarding Arthur’s omission from a 10th century poem from the Book of Taliesin called ‘Armes Prydein Vawr’ or The Prophecy of Prydein the Great. I won’t go into its contents, but it is definitely a work that Arthur should have appeared in. What no one seems to take into account are those pesky Christian monks and friars and scribes and bishops. In this stanza:

“The great Son of Mary declareth, when it did not break out

Against the chief of the Saxons and their fondness,

Far be the scavengers to Gwrtheyrn of Gwynedd.”

Obviously the Christian ‘editors’ want everyone to think that this refers to Jesus. However…

“...the Great Son: though here refering to Jesus, the original word here is Mabon, who is known as the Young God, son of the Great Mother.” Source

Jesus and Mary have been substituted for the Young God and his Great Mother. Jesus could not be considered as a Young God at any time after the first century because he would have been dead. It’s much more likely that the title ‘Mabon’ refers to Arthur in an earthly incarnations or as a divinity.

[Update: The Anglo-Saxon Invasion of Britain is not supported by archaeological evidence, at least not in the sense of a full-scale war. Please see The Dark Earth Chronicles - Part One.]

Mainstream scholars love to point out that there are only three pre-1000 AD sources that mention Arthur, but I wonder how many other manuscripts have a God and his Great Mother replaced by Jesus and Mary? Unfortunately neither Felix nor I have the time to research all that would entail. Furthermore, given Arthur’s various titles as The Bear, Bear-Man, Bear Guardian, Wagonmaster, Arcturus etc., there also exists the possibility that the Christian scribes missed the associations with Arthur when translating - I mean mutilating - other texts.

Although Mr Evans-Wentz mentions the poem Preiddeu Annwfn, which tells the tale of Arthur’s quest to Caer Sidi or Annwfn (The Otherworld), he doesn’t relate it to the North Pole and simply notes that, in this instance, The Otherworld is not a place below the ground, but somewhere reachable by sea.

We have already seen how those pesky Christian monks, friars, scribes and bishops twisted and mutilated Irish history, but what happened to Britsh history with regards to King Arthur is something else on another level. Apart from the distortions, confusions, distractions, contradictions and downright lies, he was also sequestered by Christianity to become their hero by means of the Grail Romances.

Guinevere and the Court at Camelot, c. 1900, Raimund von Wichera

Public domain

Arthur’s father was Uthr Bendragon, or Uther Pendragon if you prefer. As already indicated, he was a king of the ‘Otherworld’. That places Arthur’s ancestry direct in this Otherworld.

The origin of the Round Table, according to Arthurian Legend, lies with Arthur’s father Uther, having been made at his request by Merlin in the Otherworld - ‘the realm whence all culture. Indeed all life, is derived’.

Titania (or Gwenhwyvar?)

John Simmons, 1866 Public domain

Arthur’s wife we all know as, Guinevere, although it’s actually Gwenhwyvar, which means ‘White Phantom’ or ‘White Apparition’. Gwen or Gwenn, supplies the ‘white’ part and hwyvar, is a word “cognate with the Irish word siabhradh, a fairy, equal to siabhra, siabrae, siabur, a fairy, or ghost, the Welsh and the Irish word going back to the form seibayo.” ‘Welsh Folklore’, by Wirt Sikes, 1880. It was also Gwenhwyvar’s father, King Laudegraunce, who inherited the Round Table upon Uther’s death, indicating that Gwenhwyvar and her family were also of the Otherworld.

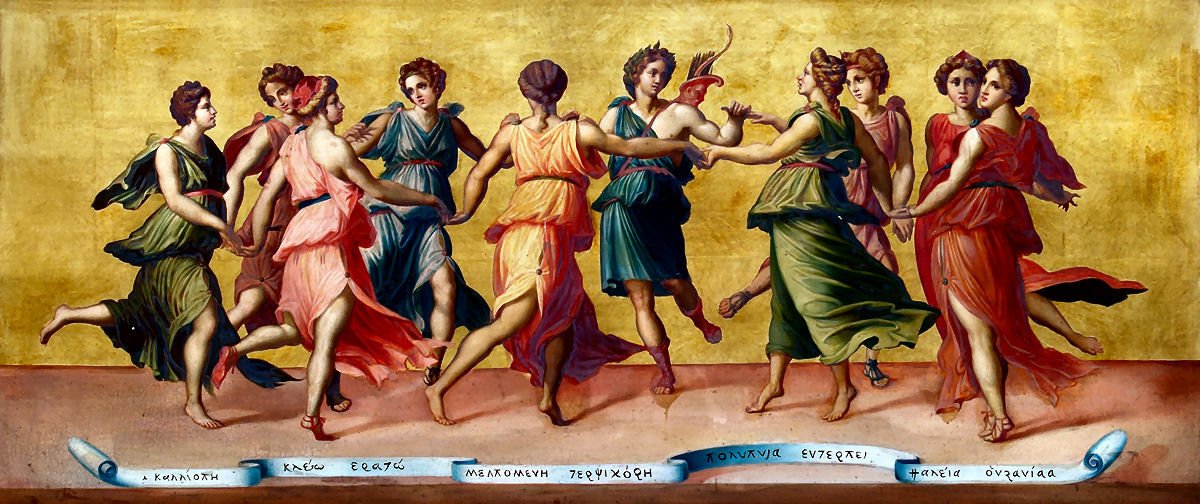

Arthur then, has a father from the Otherworld and not only a wife but also his sister is named ‘Morgan le Fay’. She mainly derives from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s circa 1150 ‘Vita Merlini’, where she is one of ‘nine maidens’ or sisters who live on the Isle of Avalon and is Arthur’s healer. The Nine Maidens have a central role in not only ‘Celtic’ mythology, but many others too including the Greek with its nine Muses.

Dance of Apollo and the Muses, Baldassare Peruzzi

Public domain

According to the Welsh Triads, Arthur and Gwenhwyvar have a son, Llacheu, who is clairvoyant and able to comprehend the secret nature of all solid and material things. The description of his death from the second part of the Welsh version of the Grail, shows him to be from another realm.

Queen Guinevere's Maying (the scene of her abducton by Melwas)

John Collier, 1900 Public domain

The abductor of Guinevere, as the story was told in the early 12th-century (‘Latin Life of Gildas’ by Caradoc of Llancarfan,) was Melwas, meaning ‘prince-youth’ or ‘a princely youth’, according to the Welsh scholar, Sir John Rhys. He also interpreted this name as an indication that Melwas was an eternally youthful being in exactly the same way as were the Sidhe and the Tuatha de Danann. Melwas is also described as ‘regnante in aestiua regione’, ‘ruler in the summer region’ which Wikipedia claims is a translation of the Old Welsh name for Somerset, ‘Gwlad yr haf’, literally ‘Land of Summer’. The trouble is “Somerset” didn’t exist back then and ‘somer’ means ‘a beast of burden, especially a horse’. The later rendition of the same incident by Chrétien de Troyes, in his twelfth century ‘Le Conte de la Charrette’, refers to the abode of Melwas as “a place whence no traveller returns.” So, we have someone gifted with perpetual youth coming from a land of perpetual summer to abduct the White Phantom or Fairy Guinevere. Melwas was a Fae on a mission.

Merlin presenting the future king Arthur

Emil Johann Lauffer, pre-1909 Public domain

Arthur came under the supernatural dominion of Merlin, who, being himself Fae, claimed the role of his protector, teacher and closest council even before Arthur was born. Of all the Arthurian characters, Merlin is the one who is generally accepted as, even at the very least, a magician. There are many tales of Merlin / Myrddyn, Emrys and Talesin who could all be different characters or the same one, but the he took on a life of his own many centuries ago and any basis in reality had already been lost by then. I remember a story concerning Merlin from some time ago that I can’t find anymore. It claimed that he was the son of a demon and a fairy. Whilst still a young boy, he was sent to work in the realm of the Great Goddess as a kind of skivvy, serving the Nine Maidens as they were tending the Cauldron of Life. At one point the contents of the cauldron accidentally splashed onto Merlin’s hand and from that point onward he was gifted with the arts of prophecy and sorcery.

The Lady of the Lake

Source

Throughout his life, Arthur enjoyed the patronage and protection of the Circe-like ‘Lady of the Lake’ known as Nimue. It was she who gave him Excalibur and it was to her that he returned it thanks to Sir Bedivere. Just as the Irish goddess Morrigan watched over Cuchulainn, so did the Lady of the Lake keep Arthur from danger.

As to the knights of the Round Table, it’s necessary to examine accounts from the Vulgate and Post-Vulgate cycles of interference. We needs must return to the account of the Fairy Gwenhwyfar’s abduction by Melwas as given by Chrétien de Troyes in his ‘Le Conte de la Charrette’ or Knight of the Wagon.

We have already seen that Melwas snatched Gwenhwyfar and took her away to his realm, which Wikipedia claims to have been Somerset. Access to this realm was via two narrow bridges; one was The Water Bridge or Ponz Evages, which was a beam one and a half feet wide by one and a half feet high passing through what sounds like a tunnel of water. The Sword Bridge or Ponz de l’Espee, was the edge of a sword that was as long as two lances. The rescue party consisted of Gawain and Lancelot. Gawain chose the Water Bridge and failed to cross. Lancelot successfully navigated the Sword Bridge.

Lancelot passant le pont de l'Épée (Lancelot crosses the Sword Bridge)

Atelier d'Evrard d'Espinques, vers 1475 Public domain

This theme of narrow bridges leading to the underworld or afterlife, features in many mythologies. The Koran states that to enter Paradise it’s necessary to cross a bridge as thin as a hair. There is a folklore tradition in Ireland and other so-called ‘Celtic’ countries which states that crossing water by a bridge or any other means, guarantees protection when being persued by fairies or phantoms. In the movies and on TV it’s always described as either putting the dogs off the scent or covering your tracks, but now we know better.

The river Nile in Egypt was always the starting point of the ‘last voyage'. Classical literature constantly describes entering Pluto’s Hades by crossing the deep, dark river of forgetfulness. Similarly, the fatally wounded Arthur himself was transported by barge or boat to Avalon. It’s also interesting to note the similarity of the Greek legend of the Rape (as in abduction) of Persephone by Pluto, the ruler of Hades, with the abduction of Gwenhwyvar

Wikipedia has this highly revealing information to offer about Chrétien de Troyes’ ‘Le Conte de la Charrette’:

“The Knight of the Cart is believed to have been a story assigned to him by Marie de Champagne and completed not by Chrétien himself, but by the clerk known as Godefroi de Leigni. A 12th-century French writer usually functioned as a part of a team, or a workshop attached to the court. It is believed that in the production of The Knight of the Cart, Chrétien was provided with source material (or matiere), as well as a san, or a derivation of the material. The matiere in this case would refer to the story of Lancelot, and the san would be his affair with Guinevere. Marie de Champagne was well known for her interest in affairs of courtly love and is believed to have suggested the inclusion of this theme into the story. For this reason, it is said that Chrétien could not finish the story himself because he did not support the adulterous themes.

“Chrétien cites Marie de Champagne in his introduction for providing his source material, although no such texts exist today.” Source

This makes it sound as if there was a Royal French story factory attached to the court and shows how easy it was for the original sources to be corrupted into fiction and romantic legend based merely upon the whims of a princess. How many other whims and even agendas have been so easily woven into the fabric of The Matter of Britain or anyone else’s Matters, for that matter?

The Knight of the Wagon

Source

The storyline of the Knight of the Wagon itself is highly convoluted and quite strange. It features a wagon-driving dwarf with Lancelot riding in the wagon after having ridden two of his own horses to death. Gawain’s pride is apparently what prevented him from riding inside the wagon. Now, in the earliest sources, Gawain is described as ‘The Knight of the Goddess’, which strongly suggests he was Fae and not mortal. Lancelot was definitely mortal. Therefore, if we relate this to the celestial Arthur’s Wagon, or The Plough, it’s obvious that Lancelot could only ride inside the wagon because he was mortal. By the same token, this also explains why Gawain did not ride inside the wagon because he was already a part of it being one of the stars that form Arthur’s Wagon – allegoricially speaking. There’s an awful lot of allegorical speech within the later Arthurian Romances.

The next we hear of Lancelot comes from a poem which is the one and only known publication of Ulrich von Zatzikhoven, entitled ‘Lanzelet’. It was written… somewhere and composed in German. Exactly who Ulrich was is not very clear at all. Lanzelet is an imitation of an unknown Old French Arthurian romance which Ulrich himself says was “the French book of Lancelot.”

The Lady of the Lake rescues the infant Lancelot

George Wooliscroft Rhead Jr. Public domain

In the poem, Lancelot is claimed to be the son of King Pant and Queen Clarine of Genewis, who were so unpopular that they were forced to flee. This, however, did not save the King who was killed. Lancelot, being one year old at the time, was hidden under a tree, but his mother was taken captive. At that very moment a fairy shrouded in mist appeared and bore the infant away to safety. This safe haven was her home on the Island of Maidens in the sea from whence derived her name – The Lady of the Lake, although the sea is a pretty big lake. Her newly adopted son, became Lancelot du Lac. Later he would marry the Fae, Elaine from which union Sir Galahad would be born, the Perfect Knight, half Fae and half human, the only one worthy of the Grail… more on that further down the line, although Galahad is a later and predominantly Christian addition to Arthurian literature.

It’s from the tale of Culhwch and Olwen, one of the earliest Arthurian texts, that we see Arthur as not only a leader of a band of strange knights, but also as the commander of Gwynn ab Nudd (Gwynn the son of Nudd) - a god and ruler of the Fae, the Otherworld, the Realm of Faërie, Annwfn. Nuada of the Silver Hand was the Irish equivalent of Nudd, being one of the Tuatha de Danann with similar sovereignty over the Irish Otherworld and the Sidhe. The Christian monks and scribes with their monkey-business turned Gwynn into a demon ruling over hell ...of course.

In the story, Culhwch travels to Arthur’s court in Celliwig, Cornwall to petition the King to help him find Olwen. This is probably the earliest reference to the location of Arthur’s court and its description very closely resembles the fairy palaces of the Irish Gentry or Tuatha De Danann.

Culhwch must marry Olwen due to a vengeful curse put upon him by his stepmother after he refused to marry his step-sister. This tale bears remarkable similarities to an old Welsh oral bardic legend recorded by W. Y. Evans-Wentz in ‘The Fairy-Faith In Celtic Countries’ entited ‘Einion and Olwen’ wherin Olwen is a fairy held under enchantment.

The Boar Hunt from Culhwch and Olwen

Source

Arthur agrees to assist Culhwch and pledges six of his finest knights – note, six plus himself makes the seven stars of Arthur’s Wagon circling above the Septentrional Islands in the north. The original names of these knights were:

Gwynn ab Nudd

Source

Arthur also pledged a bevy of superheroes, the like of which would put Marvel to shame. Besides the almighty Gwynn ab Nudd, mentioned earlier, the band comprised:

“It seems very evident that this is the magic bridge, so often typified by a sword or dagger, which connects the world invisible with our own, and over which all shades and spirits pass freely to and fro.

“In this case we think Arthur is very clearly a ruler of the spirit realm, for, like the great Tuatha De Danann king Dagda, he can command its fairy-like inhabitants, and his army is an army of spirits or fairies. The unknown author of Kulhwch [Culhwch], like Spenser in modern times in his Faerie Queene, seems to have made the Island of Britain the realm of Faerie----the Celtic Otherworld----and Arthur its king.” ‘The Fairy-Faith In Celtic Countries’, by W. Y. Evans-Wentz, 1911.

Merlin and the Fairy Queen, John Duncan (1866–1945)

Source

Throughout all of the Arthurian material, encounters with the Fae are commonplace, even in the later romances. There was a positive invasion of beautiful fairy women petitioning Arthur and his knights for assistance and more often than not, ending up romantically involved with most of them.

The subversion of the original oral Arthurian material by Christianity and their need to show him as a mere mortal was the first blow. Then came further corruption by the Norman-French story factories and then again more mutilation was inflicted by the Post-Vulgar cyclists who transformed Arthur and his Knights into Christian heroes of the Holy Grail. However, even after all of that it’s still so obvious that Arthur and his knights are the Brythonic counterparts of the Irish Tuatha de Danann.

Three ‘Christian’ Kings; King Arthur, Charlemagne, Godfrey de Bouilon circa 1410

Jacques Iverny Public domain

“Arthur in his true nature is a god of the subjective world, a ruler of ghosts, demons, and demon rulers, and fairies; that the people of his court are more like the Irish Sidhe-folk than like mortals; and that as a great king he is comparable to Dagda the over-king of all the Tuatha De Danann.” ‘The Fairy-Faith In Celtic Countries’, by W. Y. Evans-Wentz, 1911.

The dying Arthur was returned to the Realm of Faërie or Avalon, upon a magical boat accompanied by Fae women. Exactly who these women were or how many were in the boat or ship or barge with Arthur is anybody’s guess as by now there are so many conflicting stories it’s impossible to know. There were either three or nine of them. Three relates to the Triple Goddess feature of ‘Celtic’ mythology whilst nine connects back to the Nine Maidens mentioned earlier. According to Mallory’s ‘Le Morte d'Arthur’ they were, Morgan le Fay; Nimue, the chief Lady of the Lake; the Queen of Northgalis; the Queen of the Waste Lands ...that makes four ...bugger.

The Death of King Arthur, 1860, James Archer

Public domain

The Arunta tribes of Central Australia believe in beings known as the Alcheringa and Iruntarinia who are a spirit race inhabiting a world invisible to most other than medicine-men and seers. They are described as thin and shadowy and as always youthful in appearance. Their habitats are inanimate objects such as stones and trees and they are known to frequent sacred sites. It’s claimed that they control human affairs and natural phenomena. The Arunta also recognise that the Alcheringa must be appeased to assure their goodwill and who, when not offended, act as generous protectors or guardian spirits.

People of the Melanesian region share a very similar belief to that of the Australian Arunta in beings that they call Vui and Wui.

In Africa, the Amazulu people have the Amatongo, or Abapansi beings who behave in a similar fashion to the ‘good people’ of the Scotch and Irish. They guide the living through death; who then appear as Amatongo themselves.

Native Americans have a very strong and highly developed belief in the existence of spirits in lakes, in rivers and in waterfalls, in rocks and trees, in the earth and in the air and that these beings produce storms, droughts, good and bad harvests, abundance and scarcity of game, disease, and the varying fortunes of men. The integration of this belief with normal daily life is, or at least was up until 100 years ago, a completely natural state of affairs and played a much more influential part in their social and religious life.

The Malay Peninsula has a rich tradition of belief in various orders of good and bad spirits, demonic possession, exorcism, and black magic.

Spirit houses in Thailand

B20180, CC BY-SA 4.0

The pre-Buddhist folklore of Thailand puts the dwelling places of all of its Thévadas or gods and goddesses, in the entirety of the visible heavens and all of the spaces in-between. They are also a very close match to the Irish Tuatha De Danann. Our world is populated by minor deities known as Phi. They comprise all the various orders of good and bad spirits who continually influence man. The Phi inhabit forests, trees, open spaces and watercourses are full of them. Others inhabit mountains and high places. There’s a specific group who frequent Buddhist temples and are known as Phi nang mai; who are comparable to the Greek wood-nymphs, as nang is the word for female and mai for tree. The Chao phum phi (gods of the earth) are like house-frequenting brownies, fairies and pixies and they correspond closely to the Penates of ancient Rome. Altars to the Phi are a common sight in Thailand and may be found even outside of business premises.

The Iranians, Arabs and Egyptians, including the Egyptian Turks, all have a firm belief in jinns and afreets, different orders of good and bad spirits with all the same characteristics as fairies.

Nymph, 1929, Gaston Bussière

Public domain

The Greeks have their nymphs or nereids. In Italy the race of immortal damsels were called Fatuae. The French have fées, the Germans and Scandinavians have elves, the Swiss servans and the Romanians the lele. The Albanians have cherubim-like child-size evil fairies and also djinns - tall spiritual beings of great power.

In Indian belief, there is very little distinction between the various orders of Fae; ghosts and spirits or gods, demi-gods, and warriors; for whether incarnate in this world or immortal in the Otherworld, they behave in exactly the same manner as the Fae of Western Europe.

Apart from an apparent linguistic connection, or at least a few common letters, the Sanskrit word ‘Siddha’, and the Irish Gaelic word ‘Sidhe’ represent a similar concept. In the Vedic traditions the term Siddha refers to an enlightened soul who has attained a higher spiritual state of being. The Sidhe, or Tuatha de Danann, are also portrayed as enlightened spiritual beings. This connection is interesting and discussed more fully here.

Will Scarlet & Felix Noille

.

IF YOU ARE SEEING A LINK TO MOBIRISE, OR SOME NONSENSE ABOUT A FREE AI WEBSITE BUILDER, THEN IT IS A FRAUDULENT INSERTION BY THE PROVIDERS OF THE SUPPOSEDLY 'FREE' WEBSITE SOFTWARE USED TO CREATE THIS SITE. THEY ARE USING MY WEBHOSTING PLATFORM FOR THEIR OWN ADVERTISING PURPOSES WITHOUT MY CONSENT. TO REMOVE THESE LINKS I WOULD HAVE TO PAY A YEARLY FEE TO MOBIRISE ON TOP OF MY NORMAL WEBHOSTING EXPENSES - WHICH IS TANTAMOUNT TO BLACKMAIL. I CALCULATE THAT THEY CURRENTLY OWE ME THREE MILLION DOLLARS IN ADVERTISING REVENUE AND WEBSITE RENTAL.