The Hanseatic League - who were they really?

The Horse, Silent Witness to the Past

This article was originally posted in the forum at stolenhistory.net in an attempt to revive the original spirit of cooperative research that the forum and its predecessor once both enjoyed. It wasn’t very successful, so I have decided to withdraw from that forum and devote more time to this website.

Throughout ‘history’, up until about 100 years ago, horses have always played a major role in all of mankind’s achievements – the good and the bad. The relationship between humans and horses must go way back beyond recorded history (real or otherwise) and yet today, how much do we really know about that relationship?

The White Horse at Uffington is the oldest chalk carved white horse in Britain and it sits on The Ridgeway, Britain’s most ancient high road, which connects to other Bronze Age landmarks, hill forts and burial mounds.

Source

The Belinus & Michael-Mary Ley Lines

The Ridgeway forms part of the Michael-Mary ley line. Just to the north of the Uffington White Horse there is an intersection with the Belinus ley line at Dragon Hill, which is the longest ley line in Britain.

Source

I’m as ignorant on the subject of horses as the vast majority of people probably are these days, as I have been madly in love with motor vehicles ever since the tender age of 2 years old. Horses have never played any part in my life and now, in what may be described as its autumn, I wonder what I (and the rest of the world,) have been missing out on. Furthermore, it occurs to me that knowing more about the relationship between horse and human may be of immense assistance in judging whether any past event is plausible or implausible. For example, you couldn’t just lock your horse up in the garage when you got home and forget about it until the next time you want to use it. Horses obviously require much more maintenance and attention than automobiles. In terms of their military application in large numbers, the amount of support services must have been a significant factor in any military operation.

For example, the Norman Conquest allegedly involved between 2,000 and 3,000 horses which had to be transported across the English Channel. Horses need horseshoes which can fall off and must be replaced… or didn’t they use horseshoes in 1066? What about the saddles and the bridles etc.? How many blacksmiths would be required to change a lightbulb or look after 2-3 thousand horses plus all the weapons and armour? Did they have portable forges?

Equine matters have had an impact on our languages as well:

Equerry, Cavalry, Cavaliers, Caballo, Caballeros, Cabal etc. Curiously though the English word ‘Knight’ doesn’t derive from horse or have anything to do with horses. In fact, the etymology of the English word ‘horse’ has nothing whatsoever to do with the Latin / Greek root of caballus / kabal that gave rise to most of those words at the beginning of this paragraph.

The human-horse relationship was different in Britain to that found elsewhere. At some point in the distant past, people in Britain stopped eating horses. Instead they began to worship the horse in the form of the goddess Epona. From that point onwards the horse became sacred, just as the cow still is today in India. It makes perfect sense to me that the name Epona gave rise to the English word ‘pony’, however the modern etymologists, with their Proto-Indo-European nonsense, don’t agree, of course.

“To Epona may safely be assigned the word pony; Irish poni; Scotch powney, all of which the authorities connect with pullus, the Latin for foal: it is quite true there is a p in both.” (‘Archaic England by Harold Bayley, 1911.) I think old Harrold was taking the ‘P’ there.

“Epona, the Celtic horse-goddess, may be equated with the Chanteur or Centaur illustrated on so many of our 'degraded' British coins, and Banstead Downs, upon which Ep’s Home stands, may be associated with Epona, and with the shaggy little ponies which ranged in Epping Forest.” (ibid.)

“Ep’s Home” is Epsom in Surrey, the location of a very prominent horse racing course that’s been in operation since at least 1661, but may well have had a strong association with Epona and horses in general before that. The famous Epsom Derby is run there on an annual basis. Epsom is also famous for Epsom Salts and the saying “Goes like a dose of Salts,” is a possible link between horse racing and the discovery of Epsomite (...only kidding.)

Surprisingly in Britain, native wild horses, or ponies, can still be found in the hills of North Yorkshire; Dartmoor National Park in Devon; Eriskay – a small island in the Outer Hebrides of northern Scotland; Exmoor National Park – which straddles the counties of Devon and Somerset; in the upland areas of the Lake District and the Pennines; across Scotland – particularly in the north; the New Forest National Park in Hampshire; the Shetland Isles; and all over Welsh hillsides, such as in Pembrokeshire, Snowdonia, the Brecon Beacons and the Gower Peninsula. Source

The modern mainstream narrative disagrees about Epona being a native British goddess, in spite of the numerous White Horse carvings littered around the countryside that are found nowhere else…

“In Gallo-Roman religion, Epona was a protector of horses, ponies, donkeys, and mules.” Source

...Gallo-Roman religion? Would these be Roman Catholics who rode bicycles whole dressed in stripey tee-shirts sporting a string of onions around their necks and smoking Gauloises?

“She [Epona, not the cat’s mother] and her horses might also have been leaders of the soul in the after-life ride, with later literary parallels in Rhiannon of the Mabinogion. [1] The worship of Epona, "the sole Celtic divinity ultimately worshipped in Rome itself",[2] as the patroness of cavalry,[3] was widespread in the Roman Empire between the first and third centuries AD; this is unusual for a Celtic deity, most of whom were associated with specific localities.” (ibid.)

There was no Roman Empire of the 1st and 3rd centuries (see The Dark Earth Chronicles Part One.) They call it “unusual” for a Celtic deity to be worshipped in Rome itself – I call it misappropriation.

These are the misappropriators:

[1] Salomon Reinach, "Épona", Revue archéologique (1895:163–95)

[2] Henri Hubert, Mélanges linguistiques offerts à M. J.Vendryes (1925:187–198).

[3] Phyllis Fray Bober, reviewing Réne Magnen, Epona, Déesse Gauloise des Chevaux, Protectrice des Cavaliers in American Journal of Archaeology 62.3 (July 1958, pp. 349–350) p. 349. Émile Thevenot contributed a corpus of 268 dedicatory inscriptions and representations.

Even today in Britain it’s considered taboo to eat horseflesh. However, in Gallic France they still eat it just as they always have done, even when Epona was supposed to have been one of their goddesses. We are further presented with the usual “play it again Sam” evidence of undated inscriptions and statues in Latin and Greek showing how the cult of Epona was “widespread throughout the Roman Empire,” but of course, just like everything else, it originally came from the east. I think the appropriate expression here is “FFS!”

“The cult of Epona was spread over much of the Roman Empire by the auxiliary cavalry, alae, especially the Imperial Horse Guard or equites singulares augustii recruited from Gaul, Lower Germany, and Pannonia [WS: but not Britain.] A series of their dedications to Epona and other Celtic, Roman, and German deities was found in Rome, at the Lateran. Her cult is said to have been ‘widespread also in Carinthia and Styria [4] [WS: but not in Britain.]’" (ibid.)

[4] Kropej, Monika. “The Horse As a Cosmological Creature in the Slovene Mytho-poetic Heritage". Studia Mythologica Slavica 1 (May/1998). Ljubljana, Slovenija. 156.

So, when it suits their purpose, the mainstream are quite willing to justify their convenient speculations with “Mytho-poetic Heritage.” Now, don’t get me wrong, I don’t doubt that other tribes, races or however you want to call them, had their own horse gods and goddesses, but why does everything British have to be raped and pillaged, then redefined and attributed to some ancient empire that never existed, some other nation or “the east?”

Epona was the ancient Briton’s equivalent of the Welsh goddess Rhiannon and the Irish Macha, both of whom are closely associated with horses. Much more information is available about these goddesses from surviving mythologies, but for Epona there is just about nothing at all. If you search the internet for “Epona” you will most likely find nothing but information about 'The Legend of Zelda' video game. Rhiannon, Macha and Epona are all representations of the earth or mother goddess. These days they are generally considered to be aspects of The Morrigan, who could appear as a raven, a horse or in human form, but fascinating as it is, that’s a story for a later date.

“About 200 AD: The motif of the ‘Lady of the Animals’ lives on this religious depiction. Flanked by two horses, Epona is shown sitting on a throne holding a fruit basket on her lap. The Celtic goddess was revered as the patroness for wagoners. She was also popular among the military. The images was mainly occurred in the provinces of Gaul and Germania.” But NOT the fecking great chalk hill carvings of Britain of course and since when was Epona the ‘Lady of the Animals’ with a basket of fruit? She was a horse! The name "Epona" doesn't even appear on the statue.

Public domain

Silveryou (whilst still a member of stolenhistory.net) proposed a significant connection (or even duplication) between the Roman class of the ‘Equites’ (knights) and the the birth of the cavalry orders during the crusades, who strangely morphed into a socio-economic class of their own by providing tax collecting and banking services, and controlling the east-west pilgrimage routes. Even Charlemagne himself could have been one such example of this morphing,

Whatever you try to research these days it's always a nightmare to find reliable information. For example, The History of Horseshoes...

"Horseshoes apparently are a Roman invention; a mule’s loss of its shoe is mentioned by the Roman poet Catullus in the 1st century bc." Source

However...

"No ancient biography of Catullus survives. A few facts can be pieced together from external sources, in the works of his contemporaries or of later writers, supplemented by inferences drawn from his poems, some of which are certain, some only possible." Source

So it’s only possible that horseshoes are a Roman invention and it depends upon when you think the Romans were around... if ever

"Prior to the 19th century, horseshoes were predominantly made from natural materials such as wood or rawhide. However, the demand for more durable and long-lasting horseshoes led to the introduction of iron shoes. These new shoes proved to be sturdier and provided better traction, greatly benefiting working horses in various industries including agriculture, transportation, and warfare." Source

So, no metal horseshoes until the 1800s...

"The craft of the smith, or blacksmith, the process of forging and affixing horseshoes, became one of the great staple crafts of medieval and modern times and contributed to the development of metallurgy." Source

But no! They were medieval!

These days horsehoes can be made out of steel, aluminium, plastic and other composite materials (Source.) Why do horses even need shoes? Sometimes racehorses are run without them as it makes them faster, although that is claimed to be the other way round in the previous link. What about the North American Indians and their ‘paint ponies’, I bet they didn’t use horseshoes or saddles or bridles with metal bits. [In the original stolenhistory.net post, one contributor claimed that horses weren't native to America and were brought there by European settlers and it was they who subsequently introduced them to the Native Americans. No sources for that info were provided though.] In one of the quotes above it claims that they give better traction, but on a hard, slippery surface a horseshoe gives far less contact area between the hoof and the ground – a bit like driving on ice in a VW Beetle with standard tyres.

Farriers of the Royal Scots Greys at work, circa 1918

Source

Horseshoes are traditionally made of iron and considered to be lucky. There’s an article on this website called Iron, the Great Protector, which discusses the apparent ability of iron to repel negative entities and even maybe positive ones as well. In later research I discovered that in some traditions it was the blacksmithing that drove such entities away, in other words, not the iron itself, but the working of iron. Anyway, believe what you may regarding that, it seems there is a long tradition of belief in the ability of iron to interfere and affect energies on a non-physical level.

The reason I mention this is in consideration of the practise of ‘earthing’ or ‘grounding’. This may be considered some kind of New Ageist twaddle, but there is some logic in it and even immediately noticeable heath benefits for sufferers of ‘fidgety leg’ syndrome. Besides humans, horses and sometimes oxen, are the only animals that get shod. All other animals are in direct connection with the earth. Is there more too this connection, I wonder? If there is then would the iron in horseshoes interfere and affect whatever this connection might be in the case of horses?

Horses have been involved in recuperative therapy for children with disabilities for quite a long time. Training in Extra-Occular Vision has also been around for about 40 years, this is the ability to see without using the physical eyes… which may sound crazy. Many years ago I remember hearing about a demonstration of hypnosis whereby the subject was instructed that he would not be able to see his daughter, who was sat next to him. After coming out of the trance he was unable to see his daughter even when see stood directly in front of him. What’s more he could see objects that were held up in front of him whilst his daughter was stood in between.

Well, Extra-Occular Vision doesn’t have anything to do with hypnosis, but, if it wasn’t some kind of urban legend, it shows that it is possible. The training is most effective on children between 5 and 12 years old. It involves the balancing of both brain hemispheres, but there is so much more too it (see this link for more details.)

The benefits of EOV are stated to be as follows:

Personally, I wonder if this is nothing to do with any evolutionary process, but rather the reawakening of an ability we had in the distant past. Anyway, this does have a connection to horses…

In Cataluña, near Girona, Spain, there is a very special Equestrian Club called ‘Club Hípic Natura a Cavall’.

Here, after 15 years of research and experimentation, they have discovered that the training of EOV is greatly enhanced through the use of horses as companions of the trainees. These aren’t just normal horses…

“Ponies and horses that live in semi-freedom with their herds, that have food 24h/day as in nature, that spend many hours grazing and playing with their companions, that do not suffer pain or are subjected by force, and who are therefore emotionally balanced and willing to share experiences and learning with humans. All our ponies and horses have been bitless trained , using positive reinforcement and with the utmost respect for their physical and emotional well-being. The horses of the NAC do not wear irons in their mouths, nor horseshoes on their feet, but we take care of their hooves with the techniques of equine podology ( Barefoot ). With the help of Álvaro Cano Melchor, we embark on a journey of growth and evolution in consciousness, far beyond our limiting beliefs. The happy horses of NAC are the companions of this journey within us.”

As a result of this ‘journey’, the blindfolded children are able to communicate with the horses on a non-verbal level. The horses don’t need metal bits in their mouths to be forced in any direction because it’s all done through the non-verbal communication. The horses also relay information back to the youngsters regarding their surroundings, for example when to duck down to avoid a low-hanging tree branch.

Jacobo Grinberg was a pioneer of EOV back in the early 1980s. He was an investigator In the field of Neurophysiology and a teacher at the National University of Mexico when he first discovered the phenomena. He devoted most of his life to the study of EOV, working with blind children in particular. Jacobo Grinberg disappeared under mysterious circumstances in 1994, which has led to many different “conspiracy” theories. These days you can read many articles about his work, the vast majority of which feature the word “quantum,” which is a clear indication of misinformation.

Again, this may all sound a bit weird, but it’s all leading somewhere, I promise. At this point I would like to once more use a favourite quote…

“Though never spoken, the phonetic cabala, this forceful idiom, is easily understood and it is the instinct or voice of nature...By contrast, the Jewish Kabbala is full of transpositions, inversions, substitutions and calculations, as arbitrary as they are abstruse. This is why it is important to distinguish between the two words, CABALA and KABBALA in order to use them knowledgeably. Cabala derives from cadallhz or from the Latin caballus, a horse; kabbala is from the Hebrew Kabbalah, which means tradition ...figurative meanings like coterie, underhand dealing or intrigue, developed in modern usage by analogy, should be ignored so as to reserve for the noun cabala the only significance which can be assured for it.” (Source: Fulcanelli, The Mystery of the Cathedrals)

This information comes from Fulcanelli, also known as The Last Alchemist and is purportedly very ancient wisdom. This universal language is not only restricted to humans, but available to all of creation. It was also known as the Language of the Birds or the Language of the Gods.

“To know the cabala is to speak the language of Pegasus, the language of the horse.” From Fulcanelli’s other book, The Dwellings of the Philosophers.

Fulcanelli believed that Ancient Roman history wasn't actually real history, but a kind of series of allegories that are only comprehensible through knowledge of what he calls the ‘phonetic cabala’. He also talks about Chevaliers and knights with their code of Chivalry (another word that ultimately derives from ‘cabal’) being guardians of this phonetic cabala... obviously something went horribly wrong somewhere. He was also convinced that the origin of most European languages was actually Greek and that Latin was a later imposition. I wonder, does all of this coincide with the information given by Silveryou mentioned earlier whereby subtle changes in the meanings of words coincided with a shift from Knights with their Chivalry to tax collection and banking with a far greater increase in taxation and a much greater emphasis on financial matters. Could this in turn also correspond to the suppression of the Cabala and its replacement by the Kabbalah?

This is, of course, all conjecture. However, if at one time there was a universal language that wasn’t verbal, but ‘intuitive’ as Fulcanelli claims, perhaps this is exactly what has been rediscovered at the Natura a Cavall Equestrian Club in Cataluña. Perhaps also this language had to be protected in secret, for whatever reason, and that task fell to the chevaliers, the knights, the horsemen – hence the name of Cabala.

Obviously something went wrong at some point, the secret was lost and horses became tools for exploitation. The Cabala was replaced by the false Kabbalah and Chivalry with greed. Mention of the word “Kabbalah” in the original stolenhistory post caused an avalanche of what can only be described as nonsense, as people sought to cling on to their vested interests. As previously mentioned, the English word “horse” doesn’t share the same connection to the cabal / kabal root as found in French and Spanish, etc. Therefore Fulcanelli, being French, didn’t address it, but it’s an interesting difference to add to that of the eating of horseflesh and the White Horse landmarks of Britain.

As already mentioned, some 16 million horses and other animals perished in WWI and that was only on the allied side. The so-called ‘Great War’ marked a turning point for the role of the horse in war. Cavalry were no longer effective against machine gun fire, barbed wire, trenches and mines, but horses were still the most effective means of transporting supplies, the wounded, equipment, working to pull down and transport felled trees, moving guns and ammunition through muddy and difficult terrain, etc..

More than 16 million horses, donkeys and other animals were made to serve during WWI.

Picture: Crown Copyright (43066194)

“An attitude of carelessness toward horses persisted throughout the Crimean War and, despite the formation of the centralized Army Veterinary Department in the 1870s, reached a climax during the 1899-1902 Second Boer War, in which the British Army lost an estimated 326,000 horses and 51,000 mules mostly due to negligence. In response to a public and political outcry, reforms such as the 1911 passage of the Protection of Animals Act were implemented, and the AVC [Army Vetenary Corp] came into being.” Source

Records concerning the requirements and consequences of using horses during WWI give us the last opportunity for gathering information before the horse was replaced by machinery. This knowledge can be applied retrospectively to help us make better informed decisions regarding claims made by the official mainstream narrative in cases of large military campaigns from the past.

“For hundreds of years, huge numbers of military horses had been lost through neglect. In 1796, the Army appointed veterinary officers to cavalry regiments to reduce the number of sick and injured horses lost on campaign.” Source

“Until the 1880s, cavalry regiments were responsible for buying their own horses. In 1887, the Remount Department was created to take over this role. Animals were sourced from breeders, auctions and private families. Officers at this time still supplied their own horses.” Source (ibid.)

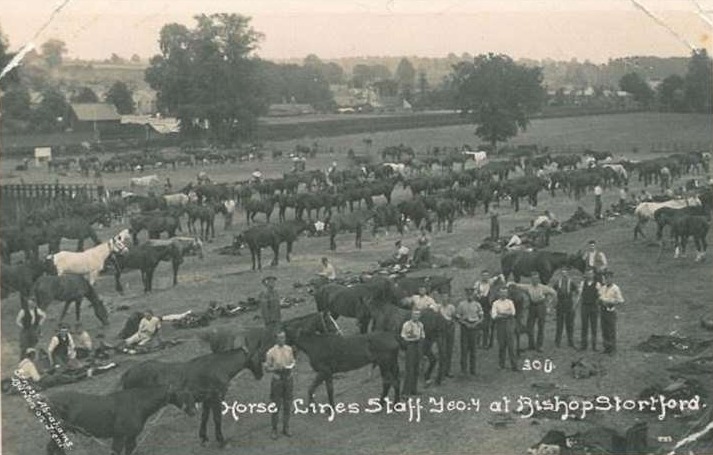

Horses and men gather in fields at Great Havers Farm in Bishop's Stortford

ahead of being sent off to fight in the First World War

Source

“The Remount Department also looked for help overseas, spending over £36 million (about £1.5 billion in today’s money) buying animals around the world, especially from America and Canada. More than 600,000 horses and mules were shipped from North America.

“Travelling by sea was as dangerous for horses as it was for humans. Thousands of animals were lost, mainly from disease, shipwreck and injury caused by rolling vessels. In 1917, more than 94,000 horses were sent from North America to Europe and 3,300 were lost at sea. Around 2,700 of these horses died when submarines and other warships sank their vessels...

“On 28 June 1915, the horse transport SS ‘Armenian’ was torpedoed by U-24 off the Cornish coast. Although the surviving crew were allowed to abandon ship, the vessel's cargo of 1,400 horses and mules were not so lucky and all perished.” Source (ibid.)

“Once on board the ships, the animals were placed in their stalls and given regular checks throughout the voyage. Despite the best efforts of the men who looked after them, many horses suffered from 'shipping fever', a form of pneumonia, and from various pulmonary complaints...

“The Blue Cross Fund, established in 1912, offered medical help and supplies to animals. This was especially important during the First World War as many new recruits had never worked with horses before and needed to learn quickly. In 1915, the Blue Cross produced ‘The Drivers' and Gunners' Handbook to Management and Care of Horses and Harness’ to provide vital information for soldiers working with artillery, ambulance and supply horses.” ibid

“In muddy conditions, it could take up to 12 hours to clean horses and their harnesses. But keeping horses well-groomed, even in the dirty conditions of the battlefield, served several purposes. Practising good grooming standards meant that the horse was always prepared for battle at a moment’s notice. Grooming also helped to prevent chafing from harnesses and saddles, keeping horses in better condition for longer. At the same time, it gave the carers the opportunity to inspect their horses for pain, wounds or sickness on a daily basis.” ibid

Unloading horses at Boulogne, circa 1916

Source

“A horse required ten times as much food as the average soldier. During the First World War, there was a distinct lack of grass for them eat on the Western Front or in the deserts of the Middle East. This meant that horse fodder was the largest commodity shipped to the front by many of the participating nations.

“The demands on transport meant that feed had to be rationed. Of all the warring nations... The naval blockade forced the Germans to supplement their horses' feed with sawdust, causing many to starve.” ibid

“Iron horseshoes wore out quickly, and usually had to be replaced every month. Farriers and shoeing smiths were needed to keep horses moving. The primary job of a farrier was hoof trimming and fitting shoes to Army horses. This combined traditional blacksmith’s skills with some veterinarian knowledge about the physiology and care of horses’ feet.

“Smiths usually carried the heavy materials they needed with them as they marched. An Army farrier would have used a variety of tools and nails to clean a horse’s feet and change its shoes. Most farriers were non-commissioned officers; the majority served with artillery and cavalry regiments. One of their less welcome tasks was the humane despatch of wounded and sick horses.” ibid

“Britain alone would lose nearly half a million horses, with an average of one horse killed for every two men. In 1916, a total of 7,000 horses were lost in one day at the Battle of Verdun… in Germany, government requisitioning of any and every available horse impacted local farms and contributed to the famine subsequently known as the “Turnip Winter.” France lost more than 700,000 horses during the war, while the German and Russian armies are estimated to have lost a combined total of 3.25 million.” Source

“Of the horses who died during the First World War, 75 per cent perished as a result of disease or exhaustion.” ibid

“During the war, horses suffered greatly from cold temperatures, long marches and poor food. Equine diseases, respiratory problems and mud-borne infections were also prevalent, as were fatigue, exhaustion and lameness caused by work. Combat injuries were not as common. But thousands of horses were still treated for bullet wounds, gas and even shell-shock.” ibid

“Many wounded animals were destroyed on the spot. But others were taken to casualty clearing stations for emergency treatment. Hospitals were established to treat the sick horses sent from the front, with equine ambulances and trailers developed to transport them there.” ibid

“The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) worked jointly with the AVC to provide care for war horses. In 1914, the RSPCA created the Fund for Sick and Wounded Horses, which helped the army create 13 animal hospitals, including four large field hospitals which were outfitted with state-of-the-art medical technology and could each hold 2,000 equines at a time.” Source

“Although it had started off as a fairly tiny force in 1914 with less than 1,000 men at its core, the AVC grew rapidly during the war years with more than 15,000 members by 1916 and over 41,000 by the war’s end in 1918. A vast majority of veterinary surgeons in the United Kingdom served in the AVC during the war. On the Western Front alone, the AVC managed a total of 20 hospitals and four convalescent depots for horses. In Egypt, the AVC ran specialized camel hospitals.” ibid

“Additionally horses, as highly intelligent animals, were often traumatized from war experiences such as the explosions of mortars and mines. Veterinarians of the AVC noted that horses with more cultivated breeding and higher intelligence levels—like ex-cavalry horses, for example—suffered more acute psychological distress than sturdy pack horses who could be trained more easily to lie down and take cover during artillery bombardments.” ibid

And then at the end of WWI, all the surviving horses, apart from those belonging to certain high-ranking officers, were shot dead. The reason given was that the cost of transporting them would be greater than the price they would fetch back in England even though the war had caused a shortage of horses. As I said before in the Original Post, It’s amazing that the soldiers weren’t also shot given their treatment when they returned home to find they had no means of earning a living.

An artillery driver and his horse rest together, showing the bond that men often developed with their service animals. The AVC made it possible for men to get their service animals life-saving treatment.

(National Library of Scotland)

So, the points raised above are the considerations of warfare pre-1900. It’s obvious that it was never just a case of jumping on your horse and riding off to invade somewhere. The logistics and practicalities involved were truly immense. Were these taken into account in the narratives we are supposed to believe today?

Having said all that, during WWII Germany was forced to revert back to a greater reliance on cavalry and horses in general, due to the various blockades of oil and coal supplies, and the heavy bombardment of their manufacturing facilities by the ‘Allies’.

The original post in stolenhistory did produce one gem of a contribution. It comes courtesy of the member known as ItsRainingRoans...

I'm not a historian by any means, and don't plan to ever claim to be one, but I have a family of farmers that dates back several centuries. My great-grandfather dealt several thousand horses across Pennsylvania in the late 1800s-early 1900s and I myself find the animals to be wonderful companions.

I've found that most of modern horse training (modern being a rough term for the past 100 years) is nearly backwards. Most behavioural studies completed on horses are done in domestic herds. Let me make it clear that while they could have a thousand-acre pasture, it is still a fenced and limited area. A majority of people in the equine world believe that herds have a hierarchical ranking, where every horse tends to 'fight' for a higher placement. The way you train a horse, which is around two steps away from the old "breaking a horse's spirit" way (who popularized such a strange way, anyway?), is by then asserting yourself as the 'alpha' of the herd. If the horse steps in your space or communicates to you in a way you find disrespectful, you are expected to use tools (halters, lead ropes - this includes the snap, the rope and the rope's end, hands, crops, whips, spurs, bits, the list goes on...) to 'correct' said behaviour. What ends up happening is that the horses will form a negative association, which then becomes anxiety, toward these items - not the kind where you shake and cry, but that presents as a stiffer gait, small 'sudden outbursts' of new bad habits and being prone to spooking. I typically refer to it as stored anxiety. It's how you end up with a horse that 'goes crazy'. Somebody gets hurt and the horse is either shot, sold or sent to a kill pen.

In reality, horses behave more like a hunter-gatherer society. They choose who is best suited for the job and let them do it. Horses can be seen as confrontational animals, but I don't see how that follows through considering how easily they bottle up behaviour when faced with a harsh owner. I prefer to look at it as a strong sense of curiosity and a vital need to socialize. Regardless of whether you have 2 legs or 4, they're going to try and include you in their herd. Lots of times, horses experiment with what people view as bad behaviour, because they want to see if they can trust you as a leader. Things like nibbling or nuzzling on you, playing with lead ropes and tack, etc. are all ways for them to engage with and learn about their environment. Not only is it the perfect chance to dissolve anxiety they may have about what they're interacting with, but it's also an opportunity to try you as a leader. As a general rule of thumb, if you step back and away from them, you're telling them you're uncomfortable with the behaviour and aren't available for their needs. If you flare up and get angry with them and push them back, you're a hothead that responds irrationally to normal behaviour. Either way, they don't have confidence in your ability to lead. Lots of times it's better to be a passive leader. Recognise the behaviour and engage with them, but take steps to ask why they're acting like that. Most of the time they just want to make sure you tolerate them behaving in a new, unusual way and they adjust accordingly.

I do think it is interesting how it can seem that humans would behave better in a hunter-gatherer type of society compared to the highly popularized "alpha" hierarchy. "Your horse is a mirror to your soul." and so on.

The 6th sense portion of working with horses actually plays a crucial role in training. A lot of people call it 'feel' and there is most definitely a telepathic element to it. Horses typically respond best to a pressure-and-release method. Whatever you engage with them to do, it's already pressure. Approaching a horse is pressure. Stepping near anywhere on a horse is pressure on that part. Looking at a horse is pressure. It's all done with an intention to have an outcome, even if you don't realize it, or if the outcome is something as simple as feeding a slab of hay. Horses recognize this as it's a feeling they can experience with other herdmates.

Pressure is a type of engagement, it's like walking up to the horse and asking "Hello, I'd like to do something with you, is that okay?" Typically this is where modern day training interferes. If the horse chooses 'no', people tend to find some way to make the horse do it. They think this is positive training because eventually, the horse will do it when they ask- but that is because it is no longer a question any more, it is a command. They have no choice but to participate. On the other hand, if the horse chooses not to engage, just wait. Maybe ask again a couple minutes later. Respect the decision your horse makes, and soon he will find the courage to say yes. The horse will choose to follow you, because he knows you pay attention to how he feels.

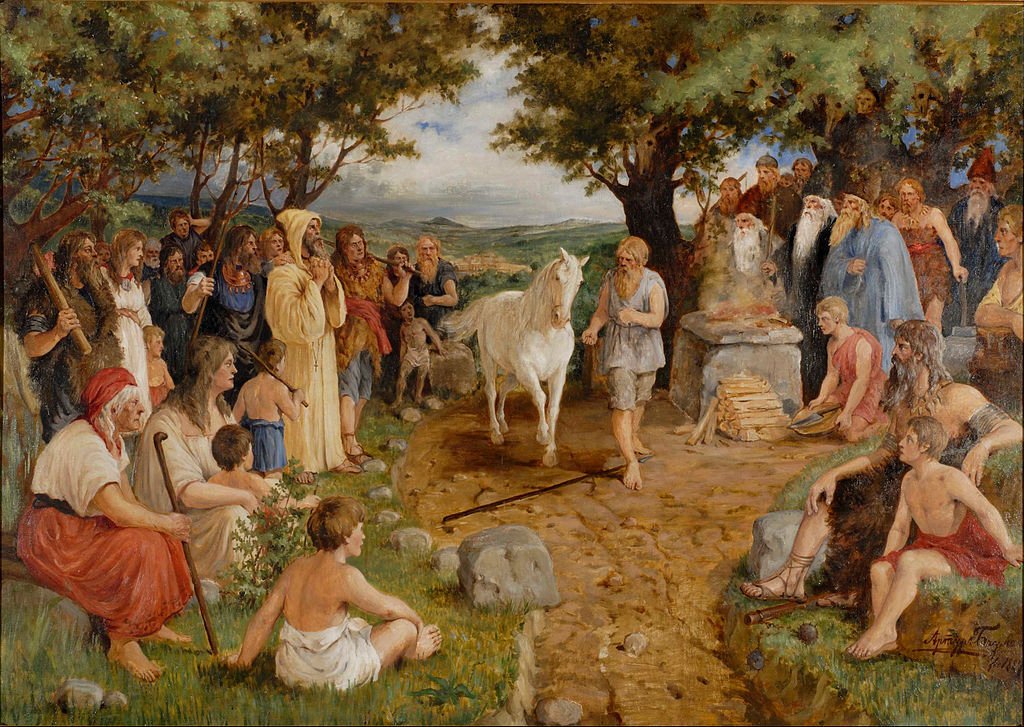

The Horse of Destiny by Arturs Baumanis, 1887

Latvian National Museum of Art, Public domain

Typically speaking, when dealing with a horse that has been traumatized by a previous owner or experience, his creativity will be impaired. If you ask an unburdened horse to do something, he will begin to look for answers. He will look for the 'right thing', whatever that may be and as he gets better and better at it, he will find the answer faster. A traumatized horse typically lacks access to this instinct because he is used to relying on everything the human makes him do, so when he is given the opportunity to give his opinion, he tends to get anxious at the lack of direction, even if the direction he was previously getting wasn't healthy. Lots of times the horse acts defensive, maybe showing some of the well known ear-pinning, biting, kicking, anger reactions, because he assumes that eventually you will get tired of his lack of response and punish him. He feels he should lash out first, to defend himself from the eventual pain. It is not impossible to unteach this, and bring back that curiosity. Learning becomes a fun game for him when he realizes that no matter what he fails to understand, you will break it down for him to better understand instead of punishing him. Gradually, he will look for answers again, and you will get a happy horse who feels safe telling you when he isn't confident in his ability to perform a task.

Release. It is the follow-through of pressure. It has been referred to as the 'reward', but it's really just the answer to the question you're asking. For example, say you were to put pressure on a horse's left flank, because you wanted him to step to the right. When he recognized you were there, he would step to the right. You would then step back and give him space, removing that pressure and thus creating a kind of release.

Now that, but with more finesse. Lots of times when you are teaching a horse a new response, if you want to resolve anxiety instead of building it, you've got to break the task down more than that.

Say you are trying to get the horse to move to the right like before, but he doesn't want to. Naturally, you'd respect him and step back, and ask again later. Wait until he is comfortable, and reinforce that with smaller things. Let's say you step toward him, and he flicks his ear back at you. He may not be willing to do as you ask yet, but his thoughts went to you and he put his ear back as if to say "I recognize you're back there, and I'm curious as to what you're doing." That's more than enough of a first step to me, so I step back and release that pressure. Maybe he does that ten times over, but eventually he might look back at me and point both ears at me. I'll step back for that, because that's more of a response than last time. Maybe I'll even pet his muzzle if he shows no objection to it. Eventually I'll step closer and he'll move his hindquarters, so I'll step back and engage with him and I won't ask again. Soon he figures out that he did what I wanted, so I said "that'll be all, thank you." and moved on. Horses value it a lot when you pay close attention to small bits of body language, like where their ears are, where their eyes are, and how they're standing.

I don't know much about the psychic aspect of things, but I really wish I knew more. I'm certain you could communicate entirely with a horse through telepathy, frequency, brainwaves etc. I don't think the way I believe is the correct, or more specifically, the whole way to interact with a horse in the slightest, but I think it is a small portion of it, and a step in the right direction.

I believe you reach a more connected state when all anxiety has been resolved and both you and the horse are attuned to each others behaviour. At that point, I believe the horse starts to do things for you without you asking - not because he is used to your routine, but because he senses what you're thinking. Horses can definitely tell where your mind goes, more so than you can. I'd love to expand on this but I'll let this portion be for now, I've done enough rambling for the moment.

I plan to keep any and all horses I own barefoot and bitless, and I definitely think you're onto something with interrupting some sort of energy field. I look forward to dipping into this thread from time to time as there's definitely a lot of interesting thoughts and theories packed in here. For what it's worth, I'd try looking around with swirlology/whirlology. I don't know a lot about it but I reckon you could probably find a deeper meaning. It's similar to the myth that the more white feet a horse has, the more hot-tempered they are.

A whirl is the hair cowlick that a horse has on its head. Sometimes they're high or low on the head, and sometimes there is more than one. People believe it is a sign of how the brain formed/was grown and a show of what their personality is like. The general belief is that a low, single cowlick is the 'normal' way for a horse to be, whereas when you get into more complex territory, like ones that rest high on the face or multiple of them, the horse can by hot-tempered or 'crazy'. If you ask me, I think they just require more of an emotional and trusting connection with you. I guess if you're looking for an expressionless yes-man for a companion, then yes, I'd assume you'd call a slightly more complex horse like that 'crazy'. The same goes for the 'stubborn as a mule' saying. Mules tend to have very high whirls on their head, and their freeze reaction is more prevalent than fight or flight, so they tend to just stand 'stubborn' and refuse to do anything when they aren't confident in their owners.

It’s not unreasonable to assume that basis of judging a horse’s temperament by its whorl patterns was derived through close observation and the experience of hundreds of years. These days there is even scientific support for the phenomena, although it sounds even more unlikely than I would imagine most sceptics consider the traditional theory to be. Given its long provenance, I suppose the scientific clergy thought it wiser to take the “if you can’t beat them, join them” approach.

Besides Whorlology, a horse’s characteristics were also believed to be discernable from its colour and markings...

“One white foot, don't keep it for a day, Two white feet, send it away, Three white feet, sell it to a friend, Four white feet, keep it ‘til the end.”

“May 1695: Had some showers which raised the washes from the road to that height that passengers from London that were on the road swam and a poor higgler [pedlar] was drowned, which prevented out travelling for many hours. Towards evening we ventured with some country people who conducted us over the meadows that we rode up to our saddle skirts.” (‘So that was Hertfordshire: travellers' jottings 1322-1887’ Malcolm Tomkins)

(All of the information for this section comes from Jack Hargreaves.)

The art of field drainage was not introduced until the 18th century and up until that time, each village was in charge of its own stretch of road and had to maintain it without any funding. An ‘Overseer’ was appointed in each village to ensure that the road was maintained. It was an unpaid position, but anyone offered the job could be jailed for not accepting it. Naturally, road building and maintenance was spectacularly poor.

The only roads that could be travelled well in those days were the old roads along the tops of the hills, which had been used by the ancient British from the very earliest times. These were said to have been the roads used by the Iron Age people, King Arthur and later King Alfred. They were the only roads that could be travelled in winter. This is the origin of the title, ‘The King’s Highway.’ There was no chance of moving via the low roads through the valleys during the winter, which is why whole armies were known to disappear in winter and not emerge again until the spring. This wasn’t only due to the weather conditions, but also to the fact that most of Britain was covered in thick forests in those times and the Highways were relatively free of trees.

This situation didn’t change until the 18th century when Turnpike Roads were introduced. These were built by Turnpike Trusts, which were cabals of local businessmen who financed the construction and were granted the right to build by an Act of Parliament. They, of course, were also given the right to put gates across the roads at various points and charge travellers a Turnpike Fee. The roads were well engineered, none of them having a gradient greater than 1 in 30, which could be managed at “full trot” by a fully loaded coach and horses.

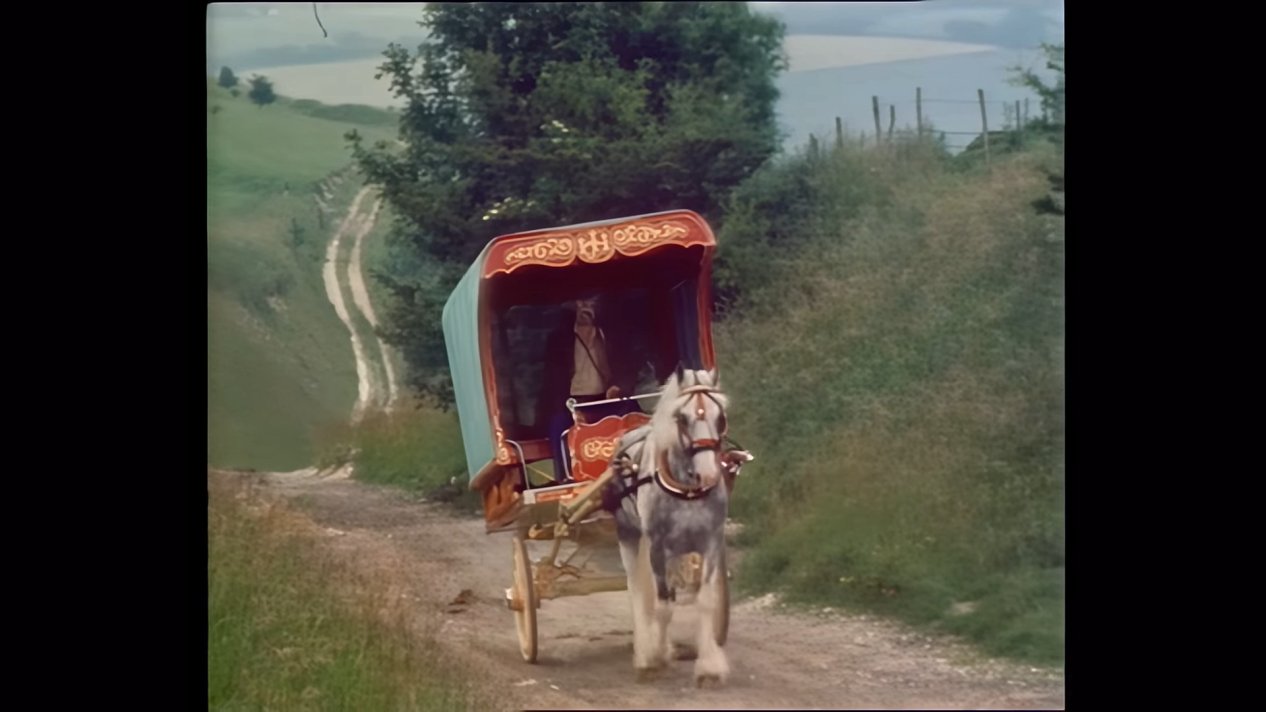

Last remaining Turnpike Gatehouse on the Great Western Turnpike Road in England.

(Jack Hargreaves)

Obviously, the Turnpike Gates had to be guarded as they were not popular with travellers, particularly the drovers with their cattle and sheep. Initially the penalty for breaking a Turnpike Gate was six month’s imprisonment, but later it incurred the death penalty... which seems inappropriately excessive.

Coaching Inns were built at intervals along the Turnpike Roads. These intervals were quite small as horses driving coaches had to be changed every 10 miles (16 kms) and some of the coaching inns provided extensive facilities for changing horses, one in Barnet, North London, had a stable of 1200 horses available for coach changes.

This revolution in road building also shaped the development of the rural countryside in Britain. Market Towns began to develop within a web-like formation, with each one radiating its tentacles out to connect to the next nearest Market Town and also to the surrounding villages. All the Market Towns were between 10 to 14 miles apart (16 to 22.5 kms.) This meant that the local people were always within 5 to 7 miles (8 to 11.2 kms) of a Market Town, which was at most about a 3 hour walk or less by horsepower. The development of the railways and even later motor vehicles completely changed all of the communities that had grown around these Market Towns and now there are none remaining.

Shaston Drove near Whitesheet Hill, Wiltshire, once part of the old King’s Highway.

On the oldest maps it’s referred to as the 'Herepath' which means path of the army.

Source

Before the 18th century the King’s Highway would not have had such comfortable gradients, therefore progress would have been slower on horseback or when driving a cart or a coach. In fact, it would take between 4 and 5 days to travel 100 miles (161 kms.) Originally the Highway would have been about 40 yards (36.5 m) wide and there was a law stating that no debris should be left within 40 feet (12 m) of the road to prevent ‘footpads’ or ‘highwaymen’ using it as cover from which to leap out and exclaim “Stand and deliver!”

The Knights of St. John, or Knights Hospitalier, provided shelter for pilgrims who used the Highways in various villages that could be accessed via intersections or crossroads. Many such crossroads featured ‘Huts’. This was the ancient word for an Inn combined with a shop, what the Spanish still call a “Venta.” The local villagers would bring water and other goods to the ‘Hut' for sale to passing travellers. There are still some public houses in Britain with the word “Hut” in their name. The areas around the Huts would be the official unofficial camping sites for travellers on the King’s Highway. Feed for the horses was not a problem, but for water travellers relied upon the Huts. Familiarity engendered a set of social conventions at these gatherings, such as it being the responsibility of the first to arrive at the site to have a can of tea ready for those who followed.

Even after the introduction of the Turnpike Roads, the drovers still used the old Highways to drive their cattle and sheep to market, as they were less congested and more importantly, free to use. There are still sheep pens present on the King’s Highway, although by now somebody has no doubt claimed ownership of them.

It’s time to allow these Silent Witnesses to finally speak. Let’s see what they have to tell us about the good old Norman Conquest of England. Before we begin, it’s worth mentioning that there are no original authentic contemporary maps of England pre-1066. There are much later imaginings of so-called Roman Roads in England, but what Romans? Even if these are the actual King’s Highways, there are none too or from from the Pevensey / Hastings area. Some old maps show ‘Battle’ with a road going too it, but such maps are obviously much later as Battle in Hastings didn’t exist before the conquest.

September 25, 1066: King Harold defeated Harald Hardrada, at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in Yorkshire.

3 or 4 days later...

September 28 or 29: William, the Bastard, Duke of Normandy, landed his army in the south of England, at Pevensey

14 or 15 days later...

October the 14th: The Battle of Hastings began.

Distance (by car on modern roads) between Stamford Bridge in Yorkshire and Pevensey Bay is 281 miles (452 kms.)

Distance (by car on modern roads) between Hastings and Pevensey Bay is 12.4 miles (20 kms.)

These dates place the events firmly in winter time. Therefore, it was impossible for any travel other than by using the old King’s Highways.

King Harold had to be told that William had landed at Pevensey in the south. This could only have been done by messenger on horseback. So, what information can we use to make a reasonable judgement about the time taken for the messenger’s journey and then Harold’s return from the north?

In the wild, horses don’t wander very far. If they are startled they will bolt and run for about 150 yards (137 m) then stop and reassess the danger. Unlike caribou or buffalo, they never stampede or gallop for long distances. According to legend, in 1735 the highwayman, Dick Turpin and his horse Black Bess, rode from Epping Forest, just north of London, to York in order to give himself an alibi for his criminal activities. Depending on which version of the legend you come across, he rode 150 or 200 miles (241 kms or 322 kms) in 15 or 19 hours. This is, of course, impossible. It probably wouldn’t even be possible in a modern electric car which needs much more recharging than a horse does. It’s just as unlikely as the ‘posse’ that rides all day in the Westerns to catch the baddies. Even The Pony Express changed horses every ten miles (16 kms.)

In modern horse endurance trials they cover between 50 – 75 miles (80 – 121 kms) per day at a speed of about 9 mph (14.5 kph,) with three 30 minute rests during a 50 mile (80 km) trial and 5 during a 75 mile (121 km) trial. The most successful breed for endurance trials are Arab horses, but these were never used by the cavalry as they weren’t suitable for carrying the weight of a rider and all of his equipment, which weighed around 21 stone (133 kgs), although some officers would ride Arab cross horses.

Jack Hargreaves was a personal friend of the last Englishman to have fought on horseback. He led a troop of British cavalry, alongside Laurence of Arabia, against the Turks. He died at the age of 90. According to him, the art of cavalry is taking men and horses on long journeys over rough ground and bringing them to the end of that journey in a condition where they are still fit to fight. The ideal cavalry marching day was 45 miles (72 kms.) They would walk 5 miles (8 kms), trot 5 miles, dismount and lead the horse for 5 miles then remount and repeat that pattern all over again until they had covered 45 miles (72 kms.) Obviously they would also have to take frequent breaks to feed and water the horses.

So, if the messenger to King Harold was riding at full speed he would need to change his horse every 10 miles or sooner. I seriously doubt that the facilities for this were available along the King’s Highways at that time. If we assume that the messenger travelled 10 miles per day and then rested his horse overnight, the 281 mile (452 km) journey would have taken 28 days. This means that Harold wouldn’t have even found out about William’s invasion until October the 26th, 12 days after the battle at Hastings.

If we use the cavalry method of 45 miles (72 kms) per day, this gives 6.2 days for the 281 mile (452 km) journey, so the messenger would have arrived early on the seventh day of his ride which would have been October the 5th, leaving Harold just 9 days to march his army 270 miles (434 kms) to Hastings.

It’s generally agreed that infantry can march, at best, 20 miles per day or, at worst, 10 miles per day depending upon the weather conditions and the terrain. Let’s assume an average of 10 miles per day, after all, Harold and his army weren’t exactly fighting fit and it was winter. This means that it would have taken Harold’s army 27 days to march 270 miles (434 kms.) Therefore, if the messenger arrived on the 5th October and Harold’s army were ready to march on the 6th, then they would have arrived in Hastings on the 2nd November 1066 ...19 days late for the battle.

Let’s be generous and assume that Harold’s army managed to cover 20 miles per day and made the march to Hastings in 13.5 days. They still would have missed the battle by six days.

Meanwhile William, with his 10,000 soldiers, 2 or 3 thousand horses and all their blacksmiths and ferriers, plus their tools and supplies, were fighting their way 12.4 miles (20 kms.) to Hastings during the winter when all the roads in the valleys were pretty much impassable, not to mention heavily forested in those days.

These calculations assume that the messenger knew where Harold was and went directly there. It's probable that he didn't know and therefore had to take the news to London first. They also assume that Harold stayed at Stamford Bridge until the messenger arrived, but it's likely that he only stayed long enough to deal with the dead, the wounded and any prisoners. He could easily have gone to York itself, or anywhere else for that matter, as he had no idea about any sense of urgency. These factors, plus any delays caused by a lame horse or other unforseen circumstances, would serve to delay the arrival of Harold's army in Hastings even further.

Using fancy technology it has even been revealed that the ground at the original ‘Battle’ battle site would have been too boggy for horses and this is also confirmed by the monks who had similar problems where ordered to build the abbey there. Actually,there’s no ‘fancy technology’ required, just common sense.

After all of the other evidence presented in the articles “The Betrayal of Albion” and Part One of ‘The Dark Earth Chronicles’, this for me this is the final nail in the coffin of the Norman Conquest fantasy.

On a lighter note, there is a curious phenomena related to horses and ponies which in today’s cold hard scientific reality gets mocked and ridiculed more than ever. It’s referred to by various names:

Before we dig into this any deeper, let’s get one thing clear – a plait (sometimes called a braid) is not the same as a knot or a tangle. Tangles and knots can appear in horse’s manes when they have been outside in the wind and countryside just as easily as they can in human hair. These days this is the favourite explanation because, god forbid, there should be anything paranormal or supernatural about them. A plait is a deliberate intertwining of hair, or any strands of a fibrous nature.

These are deliberate plaits or braids

Source

This is just a tangled mess

Source

Back in 2009 this phenomena hit the headlines in the UK. People across the country were reporting that they were going to fetch their horse or pony in from the field in the morning and finding a perfect plait buried in its mane. Apart from the usual ‘natural’ theory, it was also suggested that the horses and ponies affected were being ‘marked’ for subsequent theft. The police found no evidence to support this though as none of the animals concerned were later stolen. The following account is from the Daily Telegraph...

“...some of those targeted have been in fields surrounded by electric fences, miles from anywhere. It is not known exactly how many horses have been targeted but at least a dozen are known to have had the treatment. Horse owner Harriet Laurie from Bridport in Dorset, a member of the Shipton Riding Club, said: <

West Dorset officer PC Tim Poole had also investigated the pagan angle and he told the Daily Telegraph (and Paranormal Magazine)...

“We did have intelligence from Avon and Somerset police that it is a gypsy trick, which it may or may not have been. But we have some very good information from a warlock that this is part of a white magic ritual and is to do with ‘knot magick’. It would appear that for people of this belief, knot magick is used when they want to cast a spell. Some of the gods they worship have a strong connection to horses so if they have a particular request, plaiting this knot in a horse's mane lends strength to the request. The fact that this rash of plaiting coincides with one of their ceremonial times of year adds weight to the theory. This warlock said it is a benign activity, albeit maybe a bit distressing for the horse owner.” (ibid.)

The worship of Epona, mentioned earlier, is not known to traditionally involve this ‘knot magick’ (Source) Pagan witch, Phil Robinson, told the Daily Telegraph that pagans could not be involved...

"Some people play at Satanism and this may be related to people messing about, but it is worrying if people think it is related to paganism - we have a bad enough press as it is." Source

The story hit the Bournemouth Echo in October 2010, which was nearly a year later. It had mostly the same quotes, but no explanation was given for the 10 month delay, although some more recent incidents were reported and they are a bit slow down that way. It’s a shame nobody did any proper research on the subject...

“In the Middle Ages, it was said that this clairvoyant power of horses made them a special target for witches and faeries to steal them from their stables and fields. They believed the witches tied ‘hag knots’ in the horses manes to help them hold on while they ‘hag rode’ them to coven meetings. Then they brought them back, sweating and exhausted, just before dawn. Ribbons tied in a horses tail or mane today are a left-over of this superstition. Ribbons were protective, enchanted ‘knots of magic’ to protect the horse from the witches or fairies power. If horse-owners found a lucky stone - a stone with a hole in it - they threaded it on a string, then hung it round their horses neck, or on a nail in its stall, believing this would help protect their horse from being ‘hag ridden’ by witches.”

I apologise that I don’t have the original source for this information, although the following paragraph, which came from the same webpage, shows that there’s also a theory that they’re caused by Bigfoot. I found it in an American horse forum...

“Some of the old range cowboys used to believe in this as well. If the horses tied to a picket began to cause a fuss, whinnying and stomping, there were some cowboys who would refuse to check on them due to the belief that witches were trying to ride them away. These cowboys believed that if the witches were caught, the witch would put a hex on the cowboy and his horse causing bad luck and eventually death.”

So this belief is common to Britain and America. I know that the Spanish also have the same tradition.

The “hag rode” and “hag ridden” terms are very interesting. It’s claimed to come from the mid 17th century and was also said to be a description and the cause of, sleep paralysis. (Source) “Hag-rid” also comes from the same period and has the same meaning (Source.) Curiously the connection with horse and pony plaits is never mentioned in the official definitions and etymologies. Even more curiously, ‘Hagrid’ is also the name of the friendly giant caretaker of Hogwart’s in J. K. Rowlings’ ‘Harry Potter’ books.

Shakespeare also had something to say on the subject in his play Romeo and Juliet, Act 1, Scene 4:

“O, then I see Queen Mab hath been with you. She is the fairies’ midwife, and she comes In shape no bigger than an agate stone on the forefinger of an alderman, drawn with a team of little atomi over men’s noses as they lie asleep...

...And in this state she gallops night by night through lovers’ brains, and then they dream of love…

...This is that very Mab that plats the manes of horses in the night and bakes the elflocks in foul sluttish hairs, which once untangled much misfortune bodes.”

It’s claimed that Shakespeare wrote Romeo and Juliette between 1594–96. This was before the mid 17th century use of the terms “hag ridden” and “hag rid.” Queen Mab seems to be an creation of Shakespeare’s and she makes later appearances in fictional works by authors like Shelley. We have discussed Shakespeare and his knowledge of the supernatural previously in relation to “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” which is actually an abduction story, so it’s highly likely that he knew of the ‘elflocks’ phenomena from his trips to Wales rather than having inventing it. The negative aspects, such as “much misfortune bodes” when combined with the earlier information regarding witches and the stealing of horses is indicative of the demonisation of everything related to the Realm of Faërie as discussed in our article ‘A Quest for the Lost Realm of Faërie’. Traditionally, in Wales, anything out of the ordinary that happened to horses was always blamed upon the Tylwyth Teg or ‘Fair-folk’, a separate race to humans who possessed supernatural abilities. They are the equivalent of the Irish ‘Gentry’ or Sidhe.

It’s possible to pick up the remaining threads of a less hostile account of the Fairy Knots from various sources around the internet, but hunting down the original source would require much more research, which would delay the publishing of this article even longer. However, now that I am aware of it I may stumble across something whilst investigating other topics. The gist of the tales are as follows:

The Fairy Knots are created by the ‘Fair Folk’ to be used by them as reins and stirrups. There appears to be a selection process involved whereby only certain horses, or ponies, are chosen. Who knows, maybe they need the consent of the horse. They always return the horse before sunrise after the night’s adventure. They leave the Fairy Knots in the horse’s mane. There are two schools of thought on this: one claims that they are left ready for the next adventure and if they are removed they have to do it all again, which annoys them. The other claims that they are left for the owner to find as a sign that the horse is special and as a request for the owner’s consent for them to return. If the owner leaves them in place they then have the consent of both the horse and its owner, which makes them very happy. If the owner removes them, then they take it as the owner refusing to give consent. This would only result in repercussions if the Fair Folk feel that the owner is not caring for the horse properly. However, as a horse owner pointed out to me, removing the plaits is caring for the horse as, otherwise, they may get caught up on something.

Speaking personally, I certainly feel that I now have a much better idea of the relationship that once existed between man (or woman) and horse in the distant past. There is also now an added dimension to be taken into consideration when examining the evidence of proposed past events.

Maybe it’s not too late for us and the horse can still lead us back to that special relationship we once had with nature and all living things.

Will Scarlet

.

IF YOU ARE SEEING A LINK TO MOBIRISE, OR SOME NONSENSE ABOUT A FREE AI WEBSITE BUILDER, THEN IT IS A FRAUDULENT INSERTION BY THE PROVIDERS OF THE SUPPOSEDLY 'FREE' WEBSITE SOFTWARE USED TO CREATE THIS SITE. THEY ARE USING MY WEBHOSTING PLATFORM FOR THEIR OWN ADVERTISING PURPOSES WITHOUT MY CONSENT. TO REMOVE THESE LINKS I WOULD HAVE TO PAY A YEARLY FEE TO MOBIRISE ON TOP OF MY NORMAL WEBHOSTING EXPENSES - WHICH IS TANTAMOUNT TO BLACKMAIL. I CALCULATE THAT THEY CURRENTLY OWE ME THREE MILLION DOLLARS IN ADVERTISING REVENUE AND WEBSITE RENTAL.