The City of London in 1666 Source

London has experienced many fires, some with much higher death tolls than that of 1666. St Paul’s Cathedral was burnt to the ground during the fire of 1087. In 1135 London Bridge was destroyed and rebuilt in stone. In 1212 there was such a terrible fire that it led to the banning of thatched roofs. Many houses built upon London Bridge caught fire again in 1633. In 1794 there was the Ratcliffe Fire and then as late as 1861 there was the Tooley Street Fire. However, none of these were given the epithet ‘The Great’. The fire of 1666 has achieved celebrity status for some reason, it even has its own interactive website and TV series.

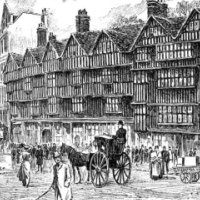

The City of London in 1666 Source

“The ‘great beehive of Christendom’, London in the early seventeenth century was the largest city in England, home to more than 200,000 souls. Its population growth, more rapid than that of the rest of the country, was not halted even by severe plague outbreaks like that of 1603, which claimed the lives of around a fifth of its inhabitants.” Source

By the time of The Great Fire in 1666, (exactly 600 years after the Norman Conquest,) England was at war with both France and Holland whilst London was still recovering from The Great Plague of the previous year which had claimed 100,000 lives. In spite of that it’s claimed that around 400,000 people lived in London in 1666, with only one quarter (100,000) of those living in The City of London itself. (London population was 200,000 in the ‘early’ 1600's, half a million by 1665… blimey.)

“The fire began at around 1am on 2 September 1666 in a bakery on Pudding Lane in the City of London… The baker, Thomas Farriner, [F: ‘Farina’ is the Italian word for ‘flour’!] his daughter Hanna and their servants were asleep upstairs. The choking smoke from a fire below woke them and they escaped out of a window onto their neighbour’s roof. Their maid was too scared to climb out and became the first person to lose their life to the fire. [F: More scared of climbing out of a first floor window than burning to death?]

“Thomas said the Great Fire was not his fault and that all the fires in his house were out except for one, which was just smouldering. We will never know for sure why the Great Fire started. Did a spark from Thomas’s oven set light to a pile of wood? If so, this tiny spark led to the destruction of a quarter of the capital city.

“The Lord Mayor, Thomas Bludworth, went to look at the fire. He didn’t think it looked serious, so went back to bed… Strong winds meant that the fire spread quickly, and the wooden buildings acted as tinder. [F: yawn] The following morning the Lord Mayor tried to stop the blaze by pulling down houses, but the fire moved too fast.” [F: Faster than the bloody Lord Major anyway.] Source

In fact Sir Thomas Bloodworth, “declared that the 1666 fire was so small, ‘a woman might piss it out’”. Even the diarist Samuel Pepys “was woken at three am that morning by his maid, but when he saw that the fire still seemed to be on the next street over, went back to sleep until seven am.” Source

So the ‘strong winds spreading the fire quickly’ story doesn’t hold water… if you see what I mean.

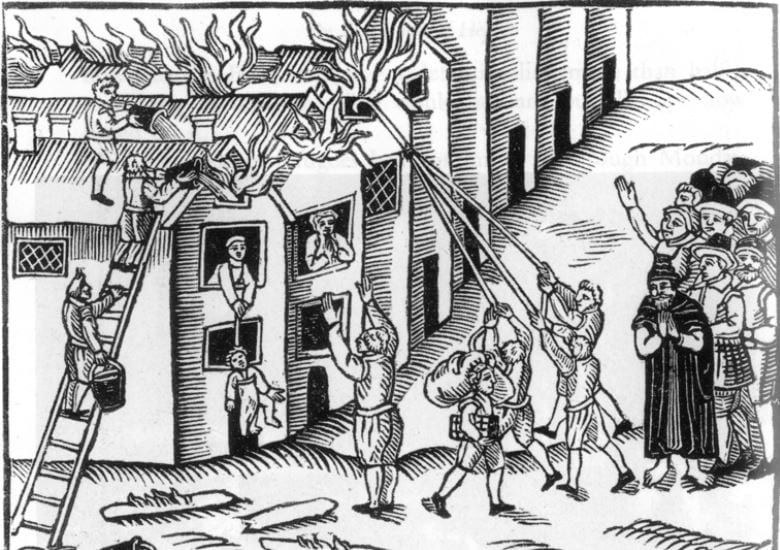

They were supposedly pulling entire houses down using these ‘fire hooks’, which were just long poles with a hook on the end...

Pulling down houses during the fire Source

“...by Monday evening, Londoners began to suspect that this fire was no accident. The fire itself was behaving suspiciously; it would be subdued, only to break out somewhere else, as far as 200 yards away. This led people to believe that the fire was being intentionally set, although the real cause was an unusually strong wind that was picking up embers and depositing them all over the city.” Source

People were so stupid back then, of course, they didn’t realise that the wind was a factor.

On Wednesday night there was a rumour spread that the French were invading the City. An angry mob formed from within the makeshift camps of the evacuated residents around the City and they rushed in wielding sticks. Personally, I think taking sticks into a burning city isn’t the best idea, but they did not get burnt.

“The streets are full of people, moving their goods... They’re having to evacuate two, three, four times,” ...and with each move, they’re out in the street, passing information.” (Source) And not getting burnt?

The King got involved and tried to organise the firefighting effort, but wouldn’t you just know it, it spread because of the blah blah blah etc. Eventually it was under control by dawn on Thursday 6th September after four days.

So how did they manage to put it out? After the fire hooks proved useless they adopted another method – Gunpowder! Yes, they went around blowing places up. Can you imagine the scene – a raging firestorm is engulfing the city and all over the place they’re wandering about with cart loads of gunpowder? It’s much easier to envision it if you ignore the ‘raging firestorm engulfing the city’ bit and instead replace it with ‘the odd blaze here and there’.

The fire was apparently used as a cover for looters. Others were suspected of spreading the fire on purpose. There still exist eye witness accounts and verified prosecutions of people spreading the fire deliberately. One person claims he witnessed ‘fireballs’… bombs?

It’s very revealing to ‘zoom in’ on The Great Fire of London and see exactly what got burnt and what didn’t.

Mostly from here…

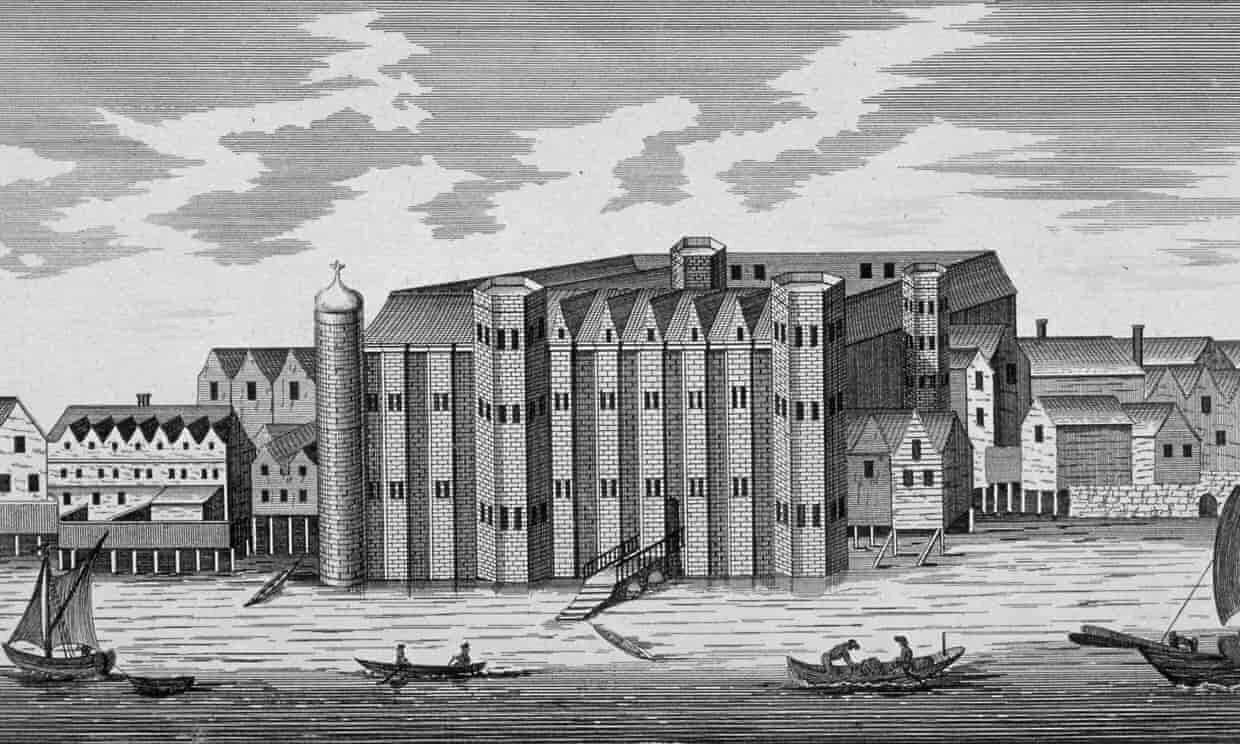

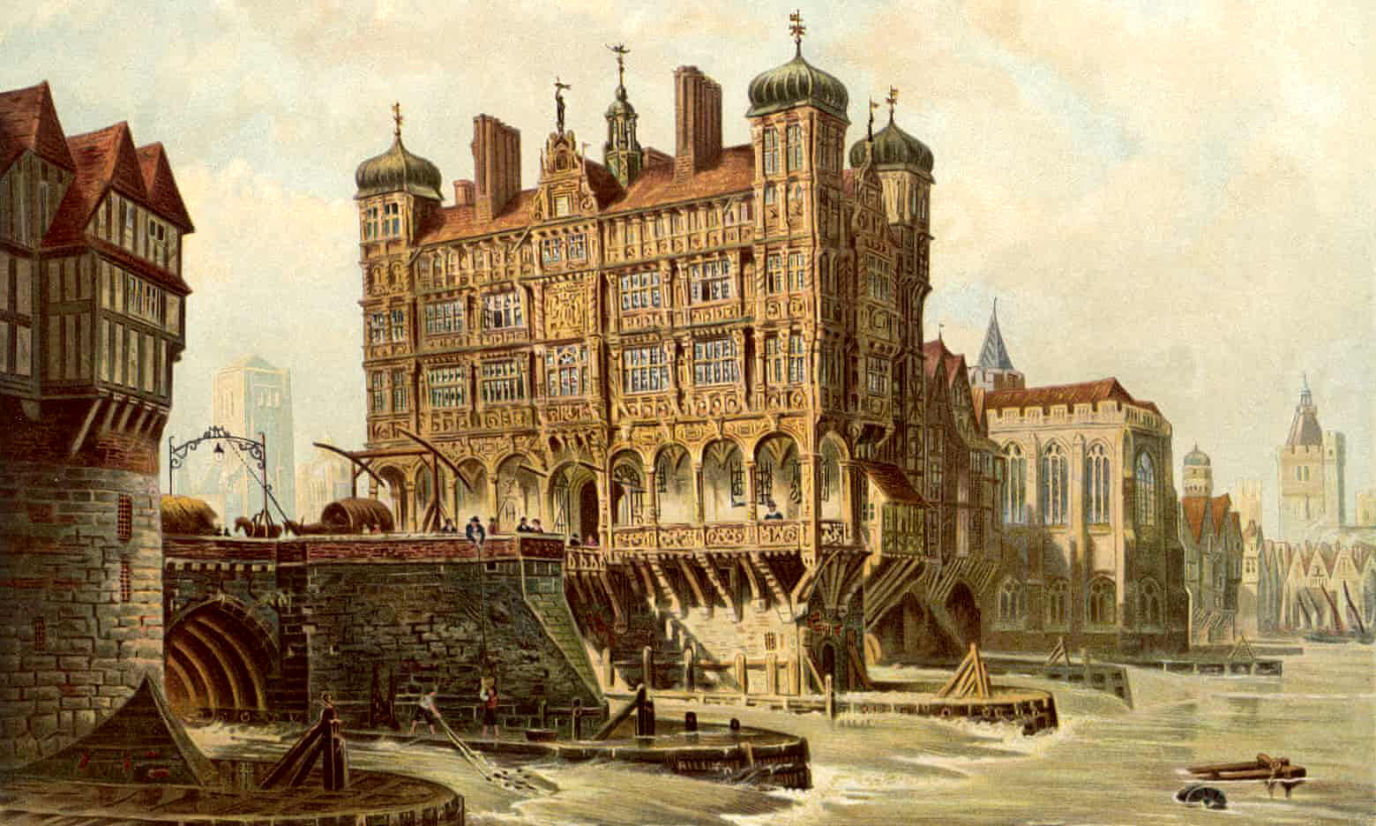

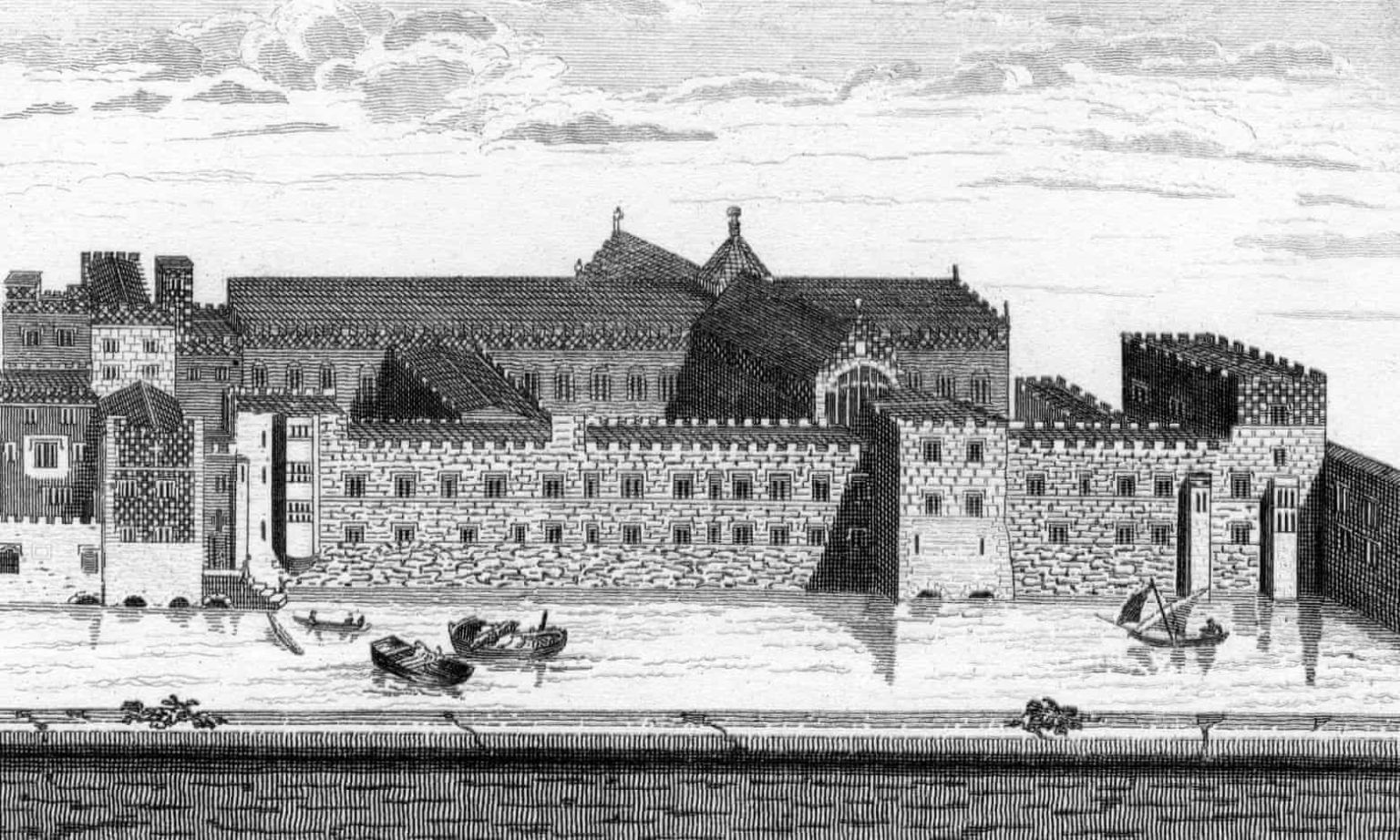

Baynard’s Castle on the River Thames – Destroyed

“After several rebuilds, it appeared on the eve of the fire as a big, brooding stone structure with gabled projecting towers soaring from the Thames, a dock, thick curtain walls, central courtyard, and meaty turrets. The scene of lavish banquets and coronations, the castle was destroyed save for one round tower.”

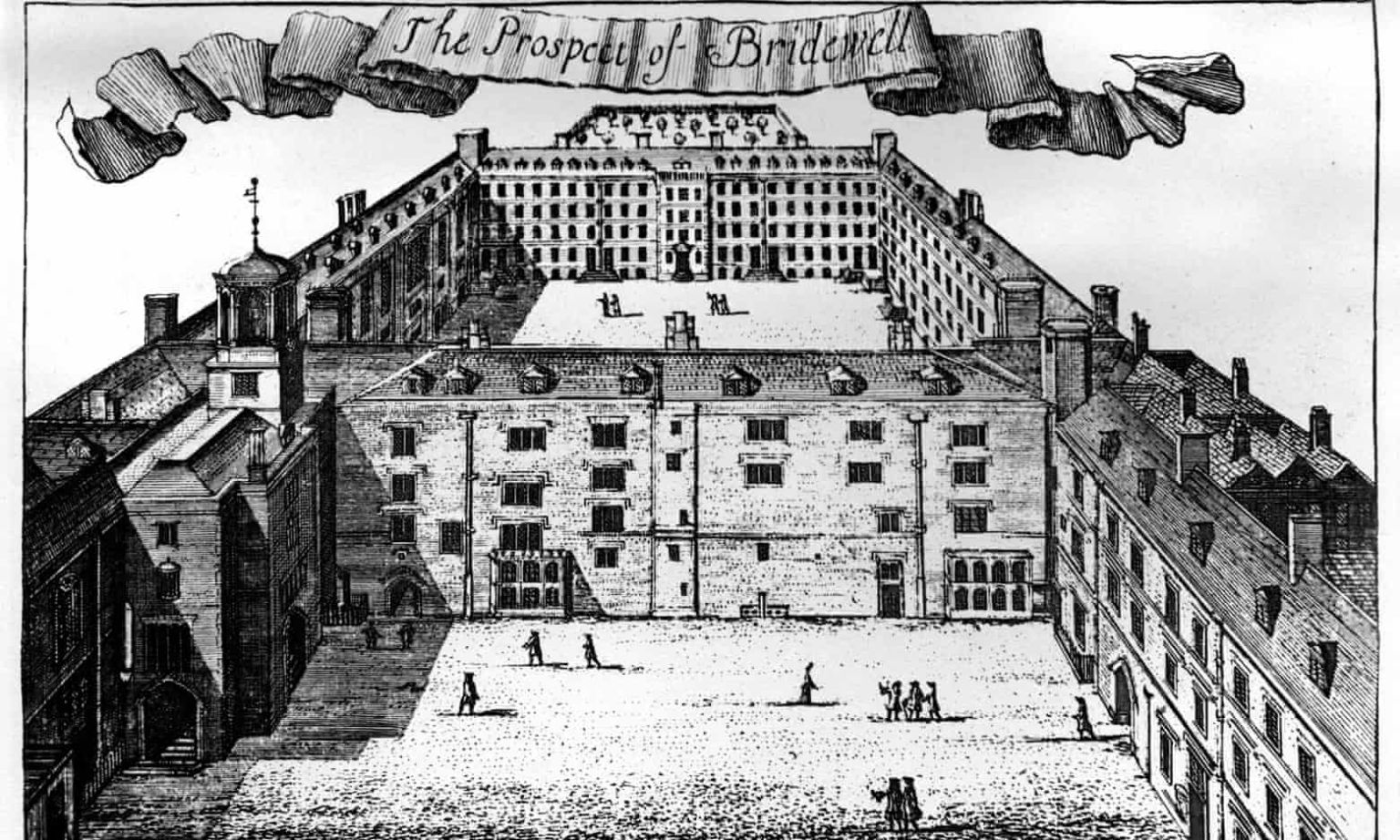

Bridewell Palace - Destroyed

“Built in 1515-20 on the western bank of the River Fleet near Blackfriars, this lost inner-city palace was one of Henry VIII’s favourites. It was a large, rambling brick structure set around three courtyards with gardens and a private wharf. An imposing feature of the riverfront.

Under Henry’s son Edward VI, it became a poorhouse but was decimated on the third day of the Great Fire. The Fleet, contrary to expectations, proved no firebreak at all even though attempts were made to pull down the riverside houses.”

F: Made of brick, surrounded on 2 sides by water, nearby houses pulled down, but still destroyed.

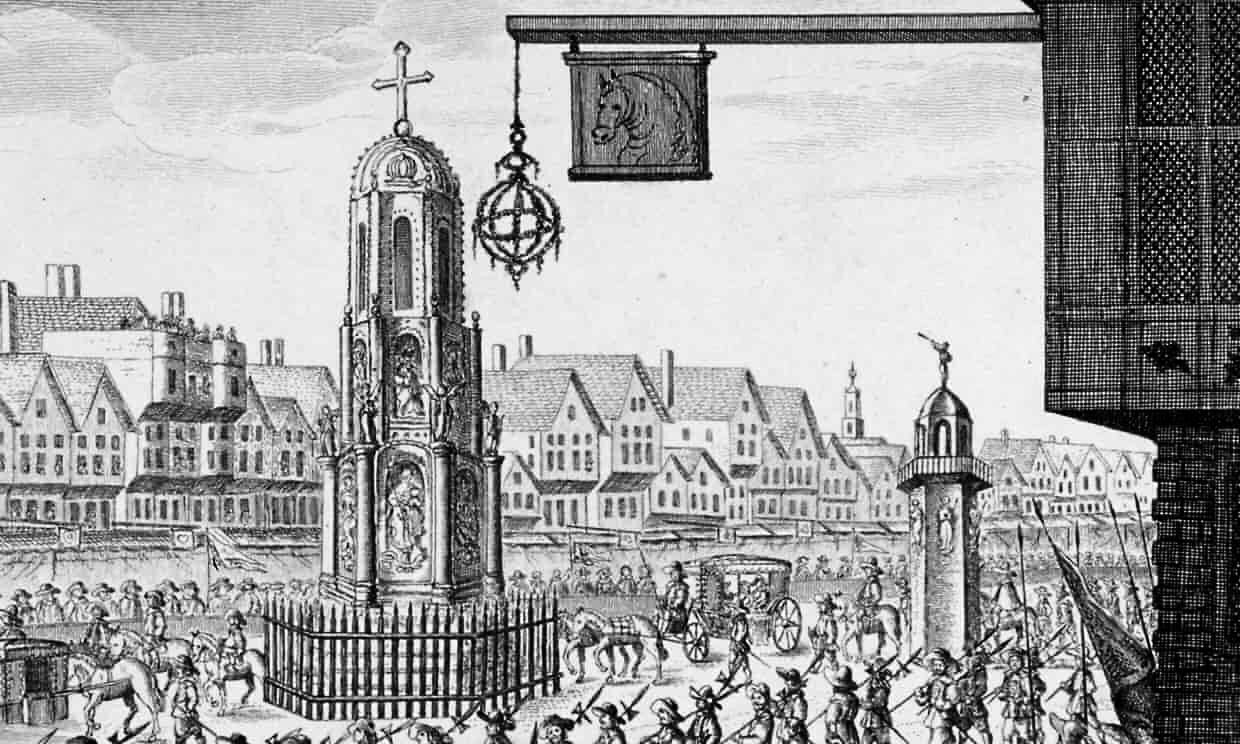

The Great Conduit – Destroyed

Advantageously located next to St Paul’s Cathedral and considerably grander and more spacious than the rest of the City’s labyrinthine streets, Cheapside – from the old English chepe (market) – was the undisputed high street of London before the fire. One of its most distinctive features, at the eastern end of the street, was the Great Conduit fountain, pictured here to the right of the Cheapside Cross… The Great Conduit itself was razed to the ground along with Cheapside on Tuesday 4th September.

[F: The narrow streets excuse doesn’t work there.]

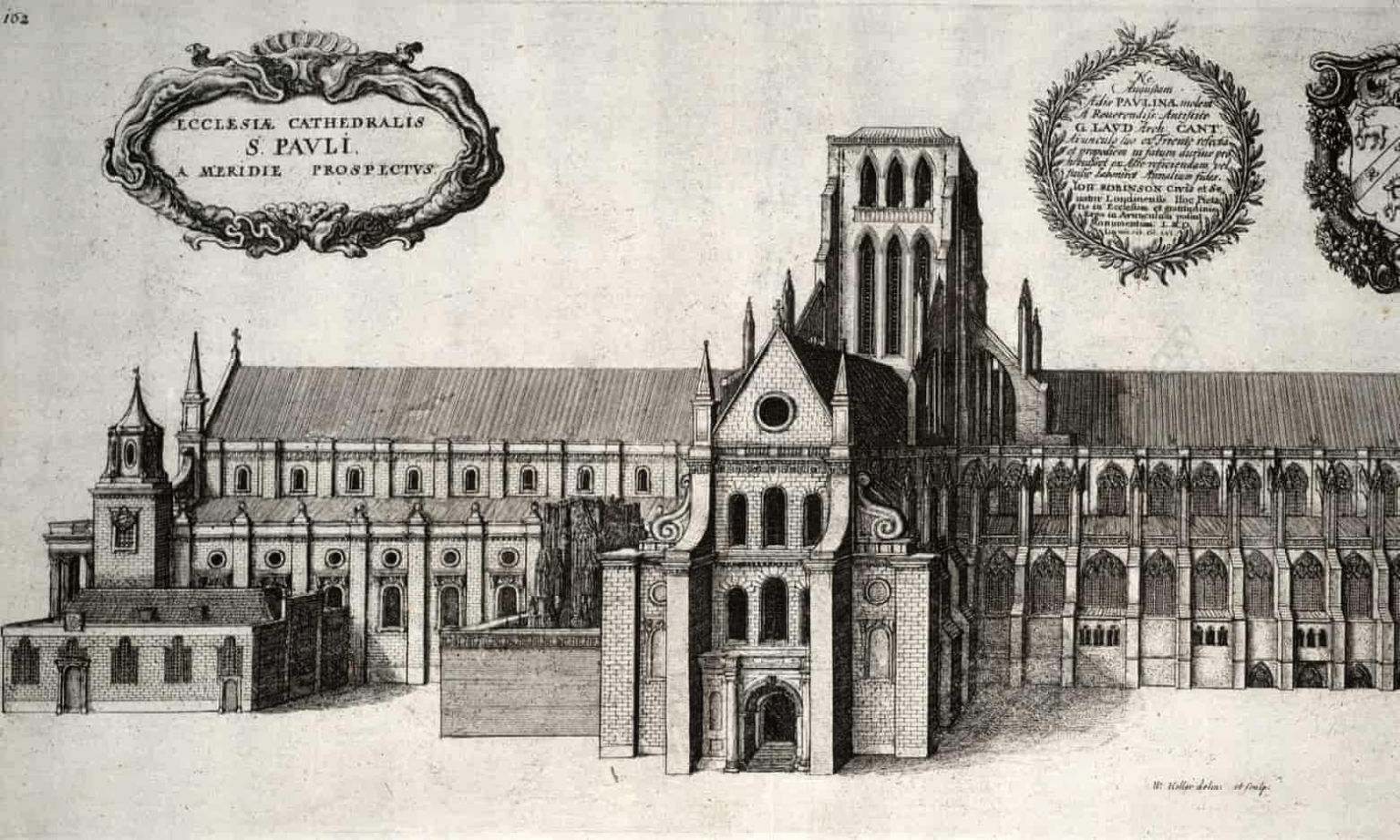

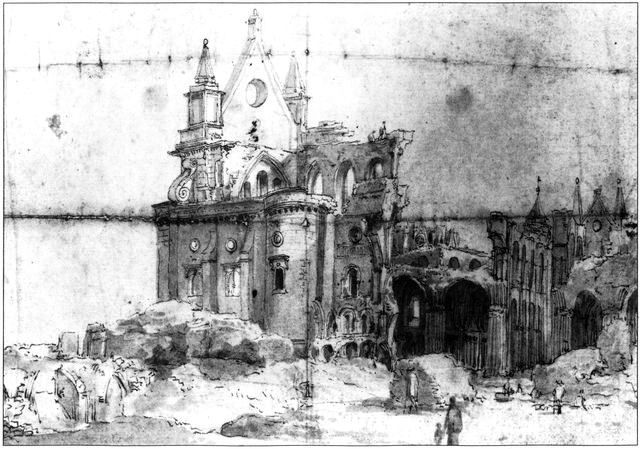

Gothic St Paul’s - Destroyed

[F: “4th September 1666, 8pm A fire broke out on the roof of St Paul’s Cathedral.”]

“Old St Paul’s was the wonder of medieval London. It was the fourth cathedral to stand on the site, built from Caen stone after the Norman Conquest, and finished in 1314. It was its monumental timber-and-lead spire that visitors noticed first (until it was struck by lightning in 1561), rising to 489 feet. Not until the BT Tower was built in 1964 would another building soar so high in London.

When St Paul’s burned down on the third day of the fire, a local thunderstorm broke out with forks of apocalyptic lightning radiating from the blazing building. [F: ...No rain then, just forks of apocalyptic lightning coming from the building not the sky!?] Eventually, the roof melted, sending streams of molten lead pouring down Ludgate Hill “glowing with fiery redness” as people ran for their lives.”

[F: Hold on… roof caught fire on the third day, entire building burned down on the third day, roof eventually melted…?]

The Steelyard – Destroyed (… or was it?)

“A collection of wharves, storehouses, a tavern, guildhall, mint, chapel, and lodgings – all engirdled by a stone wall [F: Doubtful] – amounted to a mini city-within-a-city. Home to 400 German merchants of the Hanseatic League. Since the early 13th century, successive kings allowed the foreign merchants to trade freely in England, immune from rent and taxation in exchange for surrendering their vessels in wartime. Their complex was razed to the ground in 1666 [F: Not necessarily true - see the article on The Hanseatic League], by which point they had lost most of their privileges after the jealous city guilds expressed anger regarding them towards Queen Elizabeth I.

"In 1597, Queen Elizabeth I of England expelled the league from London, and the Steelyard closed the following year." (Wikipedia) ...except it didn’t.

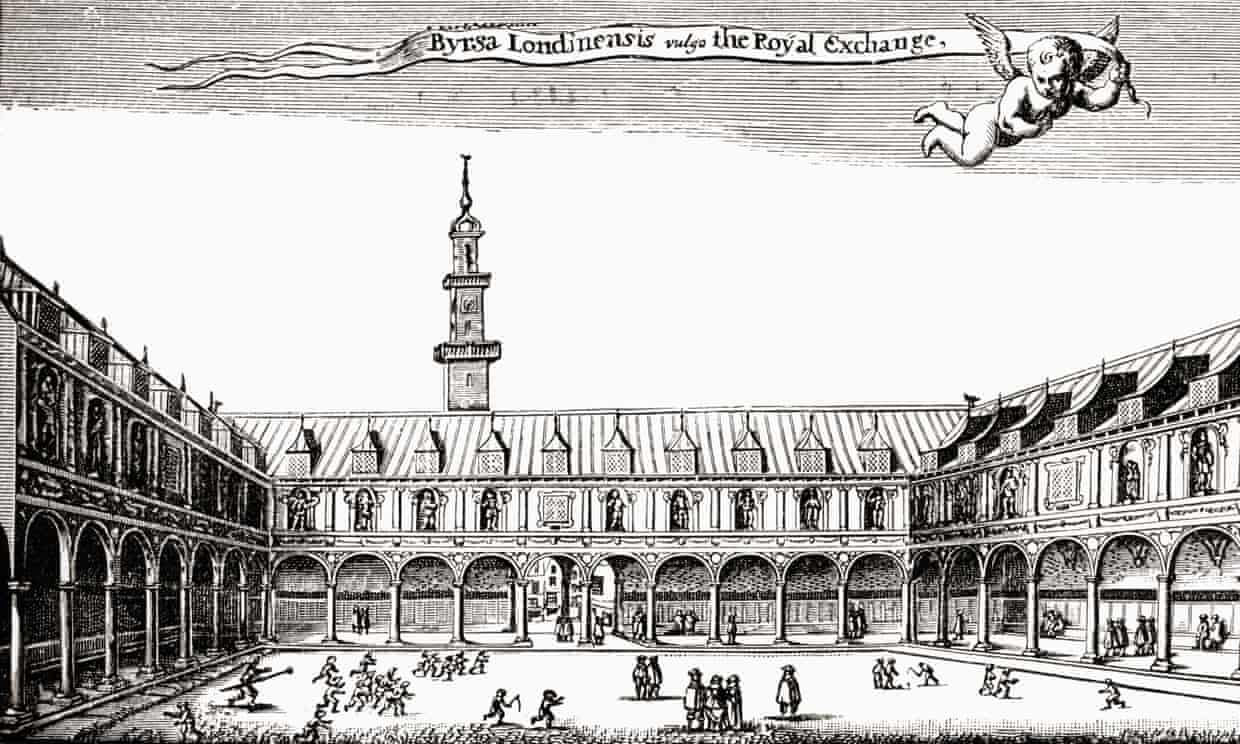

The Royal Exchange – Destroyed

“This vast, open-air trading piazza was the brainchild of the merchant Thomas Gresham. Christened the Royal Exchange by Queen Elizabeth I in 1571, it became the epicentre of England’s burgeoning trading empire, It was a broad, four-storey building with fine shops in its upper galleries, and a bell tower surmounted by a large grasshopper, the emblem of the Gresham family. Watching from niches above the colonnade were statues of all the English kings and queens since William the Conqueror.

[F: Probably not wood. Established during the Middle Period.]

Buildings that survived (mostly from here):

Nonsuch House – Survived

“This wildly eccentric, gaudily painted, meticulously carved Renaissance palace was the jewel in the crown of London Bridge. Made entirely from wood it was prefabricated in Holland and erected in 1577-79, replacing the medieval drawbridge gate. The fire only consumed a modern block of houses at the northern end of London Bridge, separated from the rest by a gap, and so Nonsuch House, built on the 7th and 8th arches from the Southwark end, happily survived – only to be dismantled with the rest of the houses a hundred years later.”

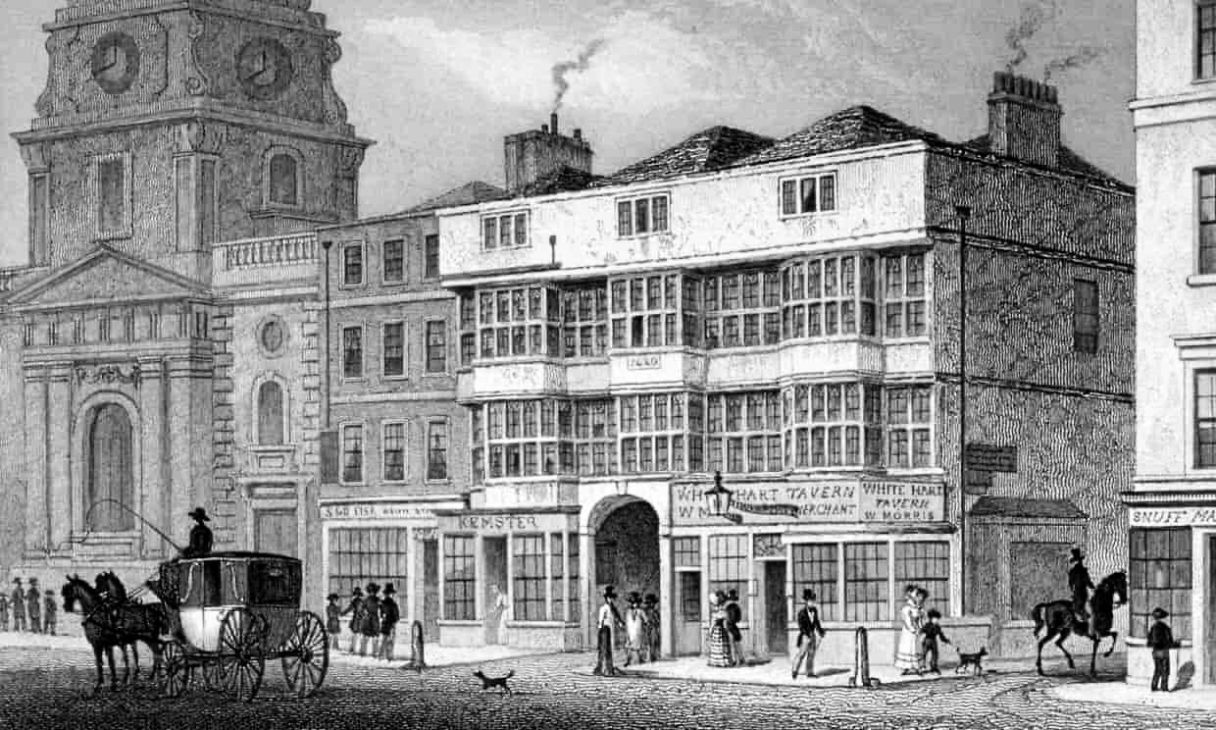

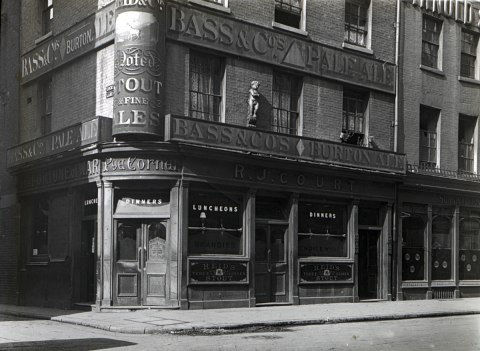

The White Hart Pub – Survived

“This old inn is a sad – and relatively recent – loss. Originally a 14th-century tavern harangued by the cries of the insane from the hospital of Bethlem next door, it was rebuilt in 1480 as one of Bishopsgate’s galleried coaching inns catering for a transient population of travellers, traders, actors, prostitutes and pilgrims.

Northumberland House – Survived

“Built in 1605, this lion-topped Jacobean palace was once an imposing feature of Charing Cross, by the equestrian statues of Charles I from 1675. It belonged to the illustrious earls and dukes of Northumberland, perfectly located to attend court and parliament.”

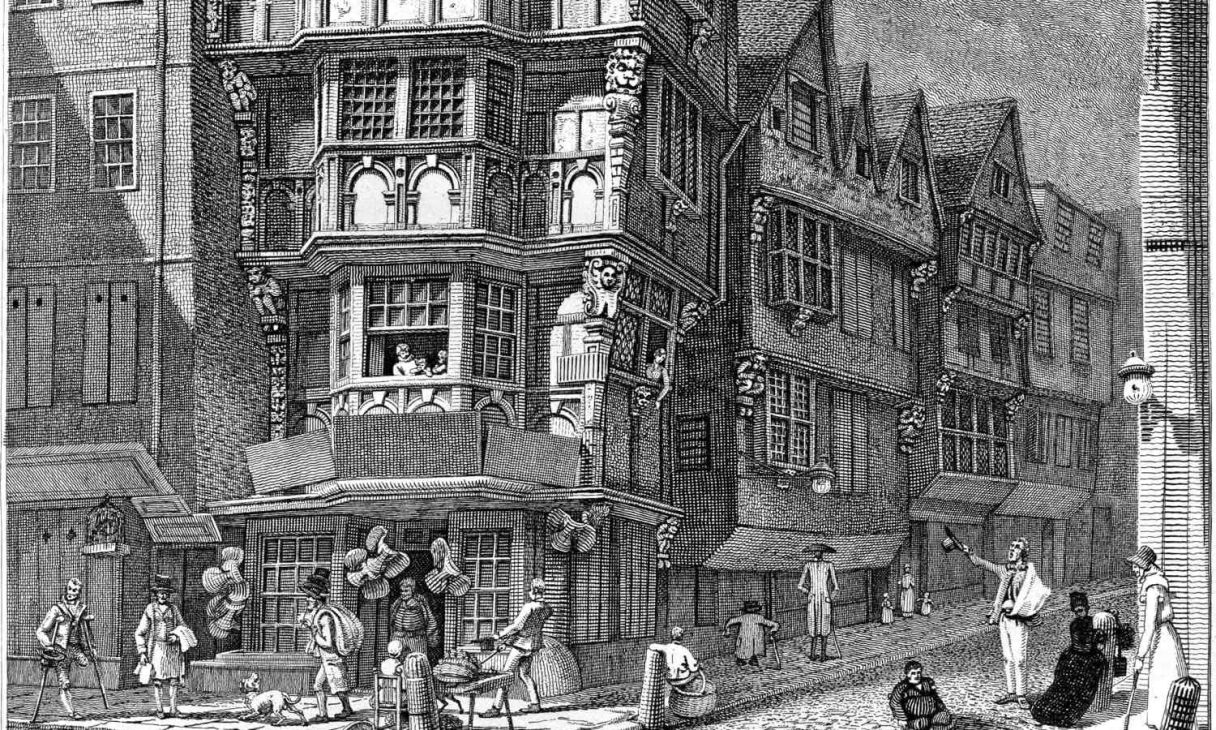

The Crooked Townhouse on Fleet Street – Survived

“On the north side of Fleet Street, the fire didn’t manage to vault Fetter Lane [F: although it managed to jump across the width of Cheapside]. If it had, then this wonderfully overwrought four-storey townhouse bulging over the corner of Chancery Lane and Fleet Street would have burned.”

The Savoy Hospital – Survived

“An initiative of Henry VII, the hospital was re-founded by Mary I, and enlarged by Queen Elizabeth I. It survived the Great Fire, but had ceased to be an operative paupers’ hospital by that stage (serving mainly as a military barracks), and was in ruins by 1800 following a fire.” If at first you don’t succeed...

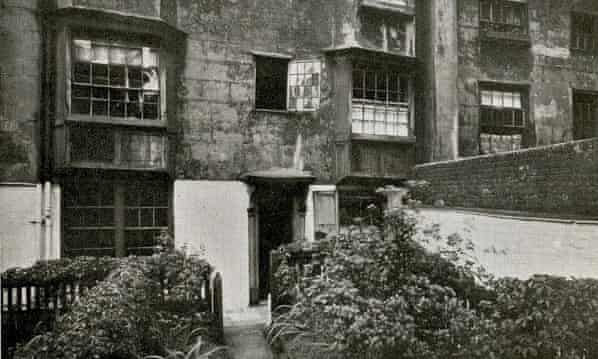

Pre-fire houses in Nevill’s Court – Survived

“Nevill’s Court was a narrow alley off the east side of Fetter Lane, named after Ralph Neville, the Bishop of Chichester who had a London mansion here in the 1220's. The court once contained one of London’s best-kept secrets: a cluster of houses with picturesque overhanging storeys and plastered walls, replete with small, fenced-off gardens. These houses escaped the fire by the skin of their teeth – but were then destroyed in the early 20th century.

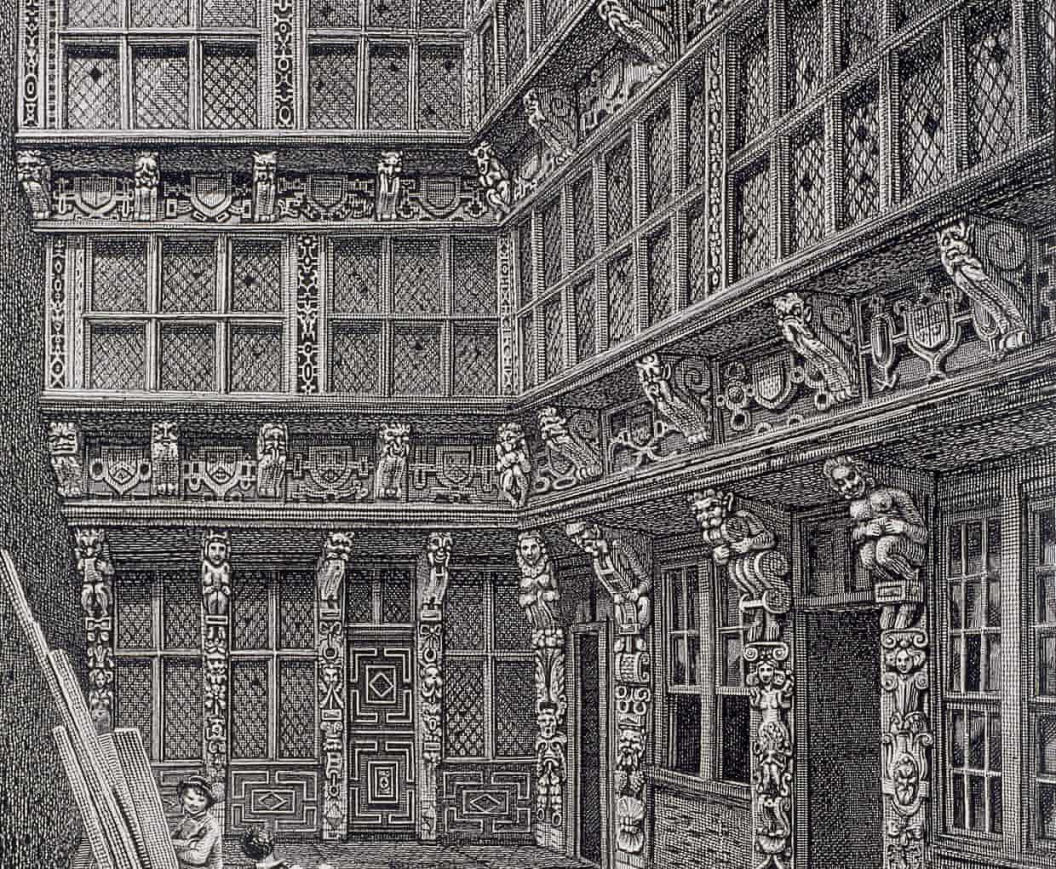

The mansion of Sir Richard (Dick) Whittington in Crutched Friars – Survived

“Fashionable glazed windows were something of a luxury in Elizabethan London, and at a time when so many dwellings had only a cloth or greased paper behind a lattice to let light in, this timber-framed mansion in Crutched Friars, to the north of the Tower of London was a work of almost criminal ostentation. It was made almost entirely from glass, with the load-bearing beams adorned with particularly hideous gargoyles as a foil to the beauty of the glass [FN: ...eh?!*] Just three streets separated it from the limits of Fire’s trail of destruction to the east. It was dismantled at the end of the 18th century.”

Shaftesbury House – Survived

“Built in brick, and ornamented with stone in a most noble and elegant manner.

It owed its Great Fire survival to the city walls at Aldersgate – but it was unceremoniously ripped down in 1882”

The Olde Wine Shades Pub (Now a wine bar), built in 1663 – Survived

“Once a favourite haunt of Charles Dickens, this historic pub was built in 1663 and even features an old smuggling tunnel leading down to the River Thames! Unfortunately there is limited information on how it managed to escape the Great Fire, especially curious as the pub is located just a few streets away from Pudding Lane.”

[F: This is a wooden structure that was at the very heart of the fire!]

The Staple Inn, Multi-use building, built in 1585 – Survived

“Having only just escaped the Great Fire by a few metres, Staple Inn stood intact until a Luftwaffe bombing in 1944 which damaged some of the structure. Due to its historic value it was subsequently restored, and is now a listed building and home to the Institute of Actuaries.”

Very Wooden.

Inner Temple Lane – Survived

“Originally part of the great 12th century estate of the Knights Templar, the stone gateway beneath the largely Jacobean structure was eventually taken over by another order, that of St John of Jerusalem (aka the Knights Hospitallers... aka The Knights Templar actually) who leased this and much other accommodation in the area to lawyers operating in the area south of Fleet Street.”

The Oldest Terraced Houses in London – Survived

“On the west side of Newington Green, perched on the border of Hackney and Islington, is the home of the oldest surviving terraced houses in London. Built in 1658, the four buildings at 52-55 Newington Green have survived the Great Fire of London as well as two World Wars.”

The Golden Boy of Pye Corner - Survived

The Fortune of War Pub - Survived

“The Great Fire of London finally stopped at a seedy corner of medieval London formed by Cock Lane and Giltspur Street. During this time, [F: the aptly named] Cock Lane was one of the few places in London where brothels were legal.”

Typical depiction of the Great Fire Source

None of the ‘Usual Suspects’ stand up to scrutiny – wooden houses, strong winds, narrow streets etc. The archetypal depiction of a sea of raging flames would not have allowed the transportation and use of gunpowder.

This was a controlled demolition.

Around 100,000 people lost their homes in the fire. Some homes burned down, but many others had been pulled down or more likely blown up.

The destruction comprised:

The north-eastern and some eastern parts, including the Tower of London, were left alone. Officially only six people died in The Great Fire. The rebuilding process took over 40 years.

Robert Hubert. a 26-year-old watchmaker’s son from Rouen, France, had been stopped at Romford, in Essex, trying to make it to the east coast ports. He was questioned and claimed that he’d started the fire, that he was part of a gang and that it was all a French plot. Hubert claimed to be Catholic, but everyone who knew him said he was a Protestant and a Huguenot. He was hung at Tyburn on October 29, 1666 on the basis of his confession, even though his story was considered unlikely and conspiracy theories and accusations continued long after his death. Source

It is often believed that thatched roofs made the fire worse, but this is a myth. Thatched roofs (which are made from reeds or straw) had already been banned in the City of London for over 450 years after a terrible, but not so Great, fire in 1212.

“Within the area of the fire no buildings survived intact above ground, [F: Not True as we have seen] though churches of stone, and especially their towers, were only partly destroyed and now stood as gaunt and smoking ruins. In many places the ground was too hot to walk on for several days afterwards.

“Within a few days of the Fire, several proposals with sketch-plans for radical reorganisation of the City's streets were put forward, including one by Christopher Wren, but they had no chance of success, because so many interests were involved and the City wanted to get back on its feet quickly. One of them, by Richard Newcourt, which proposed a rigid grid with churches in squares, was however later adopted for the laying-out of Philadelphia, USA.

“Some streets were widened or straightened, bottlenecks eased, and one new street built by carving through private properties: King Street which led from Guildhall to the wharf [FN: Why was this necessary if everything was burned down to the ground?] Markets in the streets were moved into new special market halls. But efforts to create a city with fine new public buildings and spaces did not go much further.

“Overall, there were fewer houses (some scholars say a reduction of 20%, others say as much as 39%), partly due to amalgamation of sites and some owners' wish to have larger houses. Four sizes were specified in the rebuilding Act - the largest was a house at the back of a courtyard. These grand residences were now occupied by merchants and aldermen, since the aristocracy had been moving to the West End or Covent Garden before the Great Fire

“Fifty-one parish churches were rebuilt under the general direction of Christopher Wren (knighted in 1673). Today there are 23 left fairly intact, and ruins or only towers of a further six. Often the new church had the same outline as the pre-Fire building, or the tower was retained.

“We have perhaps been overimpressed by the Great Fire, and must place it in context - the Fire, destructive though it was, devastated only about one third of the conurbation of London then standing… But it is also true that the Fire created the opportunity to build, in the central area, a city in a new form, which would quickly become the hub of the British Empire in the decades which followed. So the creation of the Empire owes something to the Great Fire of 1666. [F: Or vice versa].” Source

Old St. Paul’s Cathedral in ruins Source

“Charles II admired Wren’s design, and made him one of six commissioners appointed to oversee rebuilding work. But unlike in Lisbon, where the Portuguese king ordered [i.e. would order] a completely new city after the earthquake of 1755, Charles would not get the chance to give Wren a blank canvas. Property owners soon asserted their rights and began building again on plots along the lines of the previous medieval street pattern.

“There was no appetite (and because of war with the Dutch, no money) [F: how convenient] to get involved in legal battles with London’s wealthy merchants and aldermen. The king insisted only that the old roads be slightly widened and building standards improved.

“Aristocrats and the very wealthy had begun moving west to the new squares of Covent Garden and Bloomsbury, and many of the poorest tenants would have moved east to find cheap accommodation.” Source [F: To East Ham for example, which had been given to the Jews by Henry II.]

Ten Years after the Jewish Resettlement of England, the City of London was wiped clean, ready for its transformation.

The Betrayal of Albion Part 1: The City of London

The Betrayal of Albion Part 2: 1066 and all that Bollocks

The Betrayal of Albion Part 3: The English Revolution

The Betrayal of Albion Part 4: The Great Fire of London

The Betrayal of Albion Part 5: The Dutch Puppetmasters

The Betrayal of Albion Part 6: The Glorious Revolution

The Betrayal of Albion Part 7: Conclusion & Modus Operandi

Felix Noille

.

IF YOU ARE SEEING A LINK TO MOBIRISE, OR SOME NONSENSE ABOUT A FREE AI WEBSITE BUILDER, THEN IT IS A FRAUDULENT INSERTION BY THE PROVIDERS OF THE SUPPOSEDLY 'FREE' WEBSITE SOFTWARE USED TO CREATE THIS SITE. THEY ARE USING MY WEBHOSTING PLATFORM FOR THEIR OWN ADVERTISING PURPOSES WITHOUT MY CONSENT. TO REMOVE THESE LINKS I WOULD HAVE TO PAY A YEARLY FEE TO MOBIRISE ON TOP OF MY NORMAL WEBHOSTING EXPENSES - WHICH IS TANTAMOUNT TO BLACKMAIL. I CALCULATE THAT THEY CURRENTLY OWE ME THREE MILLION DOLLARS IN ADVERTISING REVENUE AND WEBSITE RENTAL.