Cartoon of a typical Industrial capitalist of the period… in fact any period Source

At the outbreak of WW1, the British economy was in dire straits. The Bank of England held only 9 million pounds sterling in gold reserves, which was nowhere near enough to cover the deposits and savings held by all of Britain’s private banks. This was due to rampant speculation by those very banks who had invested their client’s money in disastrous financial schemes. This wasn’t a recent problem at the time, but had been ongoing for much of the preceding century. Of course, nothing in the financial world happens by chance, there’s always a ‘scheme’.

In the 1800s the Rothschild’s pioneered the concept of foreign loans and over £100,000,000 left the British Isles during the first quarter of the century, of which £25,000,000 simply vanished without trace. (However, it should be noted that they were not the only ones making these loans.) Many of the loans went to South American countries and some southern American states and were given to finance civil wars against the Spanish. (Maybe also in the case of the southern American states, against the northern Union states.) Pretty much all of these loans were defaulted upon. This was not always entirely due to plain and simple fraud, but because the eventual terms of the loans were criminal – also it is entirely possible that they were never meant to be repaid in the first place and that they were simply a means to an end for the financiers.

“In 1832, the year of our great Reform Act, the financial houses in London were engaged in a filibustering war which has been completely crowded out from our school history books. It was the war of Dom Pedro, a gentleman who was financed by the money brokers of London and who was supplied with British officers and stores in an attempt to capture the throne of Portugal.

“Great Britain was not at war with Portugal, nevertheless the Dom Pedro filibustering expedition was organised and equipped by London banking houses, the prime motive, says Mottram*, being the unloading of insufficiently secured paper upon the investing public.” ‘The Financiers and the Nation’ 1934, by The Rt. Hon. Thomas Johnston, P.C. ex Lord Privy Seal [*Martin Mottram, ‘Stories of Banks and Bankers’]

The catalogue of usury during this period and its sheer scale is truly mind-boggling. Greece was granted an ‘Independence’ loan in 1824 by the British money-lenders. The amount was £800,000, but after commissions and fees were deducted it left only £280,000 even though interest was due on the full amount. The following year a further ‘Independence’ loan of £200,000,000 was forthcoming from the same British sources repayable at 5% interest. However, the Greeks received only £56 10 shillings per £100 of the loan which was then spent for them on the purchase of two frigates. Greece repaid nothing on these loans from 1827 until 1879, but the Rothschilds gave two more loans in 1830 and 1840 which were secured upon the country’s customs receipts.

“Two finance houses kept clear, or all but clear, of the hazardous ramps with British deposits in the South American insurrections of a century ago; these two houses were the Barings and the Rothschilds.

“By the year 1812, says Count Corti, in his story of the Rise of the House of Rothschild, Nathan was in ‘immediate touch with the private finances of the British Royal Family.' Two years later, in 1814, the Rothschilds were financing the return of the Bourbons to the throne of France, and after the fall of Napoleon at Waterloo they metaphorically had all the Governments of Europe in their capacious pockets.” (ibid)

In 1836 financial speculation focus switched its attention to the British home market. Needless to say, with the assistance of the media millions were robbed and cheated out of their life savings. The massive expansion of the Railways in Britain gave another opportunity for people to be fleeced and in 1847 when the bubble burst, just as they always burst, £78,000,000 sterling was lost by duped shareholders. Nine banks failed and Government Stocks were affected to the point the commercial credit of the country was severely threatened. The effect was worse than that of the Great Depression of the 1930s, but you won’t hear about it today.

“School history books tell us little or nothing about the Truck Acts, or of the prolonged agitations in the industrial towns which compelled the House of Commons to pass that series of measures for the enforcement of wage contracts and for ensuring the payment of wages in current coin, and the right of the wage-earner to spend his money in markets of his own choice.” (ibid)

Truck was legislated against as far back as 1465 in Britain and referred to as workers being “driven to take a great part of their wages in pirns, girdles, and other unprofitable wares.” The practise was still going on in 1849, albeit in a slightly different form - workers were forced to spend their wages in a specific shop or store. Early industrial capitalists would set up a store close to their industrial premises where they would sell food, clothes, drink etc., at ridiculously high prices (20% - 40% higher) and of a substantially poorer quality than normal. Any worker (or their dependants) who dared to shop elsewhere or complain would be dismissed.

Cartoon of a typical Industrial capitalist of the period… in fact any period Source

Often wages were paid monthly or even tri-monthly. Any loans or ‘subs’ made against future wages were subject to interest rates of between 125% and 900%.

“In 1870 the Truck Act Commissioners reported that in Shetland 'Even the paupers were trucked by the Poor Law Inspectors, who kept shops and served them with goods instead of money.'

“In the Black Country the nailmaker was compelled to buy his metal from men who were called pettifoggers, and who owned liquor shops; if the nailmaker did not drink in the pettifogger's shop he got no metal.” (ibid)

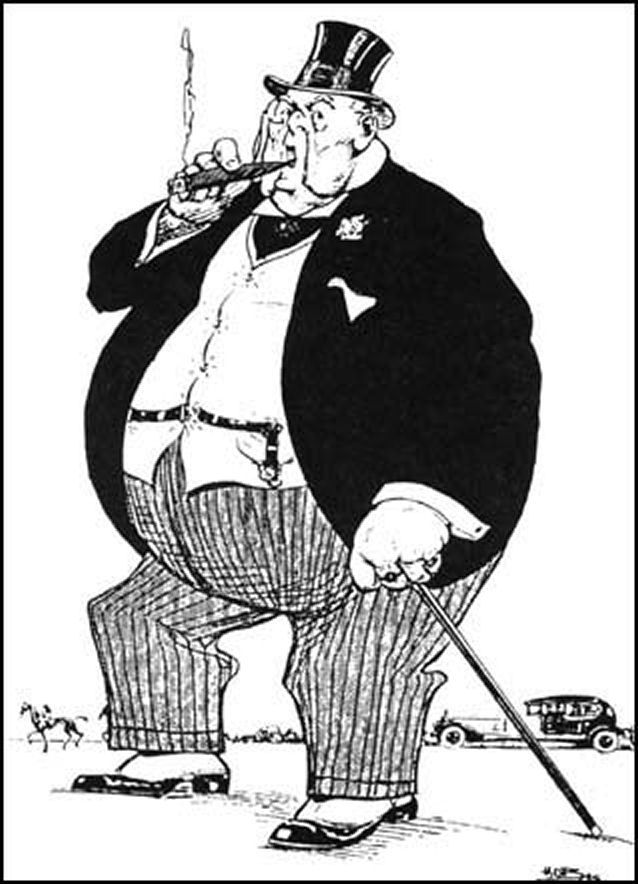

The list of Trucking abuses is seemingly endless. This is a list of fines imposed upon workers at Tyldesley Mills during the mid nineteenth century who had to endure 14 hour shifts in 80-84 degrees F with no open windows:

“Between 1665 and 1825 there were no fewer than thirty-six Acts of Parliament having reference to Truck and wages, but the Justices of the Peace authorized to enforce the laws were themselves often the employers involved, and they only enforced what law suited them. Indeed the Hammonds (The Town Labourer, p. 67) say that the Justices, so far from enforcing the Truck Acts against employers, actually used the Vagrancy Act in order to punish workmen who had the hardihood to make complaints against their employers under any of the Truck Regulations.” (ibid)

Even amidst all this misery and suffering, the financiers were still speculating, exaggerating, lying and cheating. They managed to bring Britain to its knees again during the late 1860's whereby the Bank of England had to once again print more money to kick-start the economy – they call it ‘quantative easing’ these days.

In 1875,Parliament appointed a Select Committee, led by Sir Henry James, M.P. for Taunton. It’s duty was to inquire into the methods employed by British financiers when giving loans to foreign states. These were estimated at £60,000,000 which had all been lost in foreign speculation over the previous three years to Honduras, Costa Rica, Paraguay and San Domingo. None of the capital or interest had ever been repaid. After commissions of 20% to 30% and a myriad of other charges were taken by the financial promoters in London, each state received about £60 for every £100 loaned.

“Sir Henry James denounced the financial vultures in London as ‘powerful and unscrupulous' and as ‘a band of conspirators': in turn they threatened him politically and financially ; they terrorized the Press into all but suppressing comment upon the evidence before, and the report of, the Committee; and to this day there is hardly a public library where either evidence or report is upon offer. The report was smothered, and nothing was done by Parliament to safeguard the investor for the future or to eliminate the panics and crises resultant from the amazing plunder in these foreign loans.” ‘The Financiers and the Nation’ 1934, by The Rt. Hon. Thomas Johnston, P.C. ex Lord Privy Seal

By the end of the nineteenth century the situation was so bad that Lord Russell of Killowen, then Lord Chief Justice, gave the following lecture on commercial morality to the City of London. He told the City that financial fraud was “rampant. . . fraud of a most dangerous kind, widespread in its operation, touching all classes, involving great pecuniary loss to the community, loss largely borne by those who are least able to bear it.”

Such was the situation at the outbreak of WWI.

Lloyd George was the Chancellor of the Exchequer who was faced with the gold reserves crisis just after the declaration of war in 1914. He immediately called a moratorium, whereby the banks were authorised not to pay out. It also extended the August Bank Holiday by an additional three days. The bankers held negotiations with Lloyd George and according to one of them, “he (Mr. George) did everything that we asked him to do.”

When the 1914 August Bank Holiday finally came to a close, the general population discovered that rather than being repaid their money in gold, they were issued with a new legal tender. - Treasury Notes. “This new currency had been issued by the State, was backed by the credit of the State, and was issued to the banks to prevent the banks from utter collapse. The public cheerfully accepted the new notes; and nobody talked about inflation.” (ibid)

The Bradbury Pound, so-called due to the signature bottom right

The following account of the same incident comes from the official HM Treasury’s Debt Management Office website… or rather it did, it’s been pulled.

“The threat of World War One pushed British banks into crisis; exacerbated further as half the world's trade was financed by British banks and as a consequence international payments dried up. In response to this crisis, John Maynard Keynes (the renowned economist), persuaded the Chancellor Lloyd George to use the Bank of England's gold reserves to support the banks, which ended the immediate crisis. Keynes stayed with the Treasury until 1919. The war years of 1914-18 had seen an increase in the National Debt from £650 million at the start of the war to £7,500 million by 1919. This ensured that the Treasury developed new expertise in foreign exchange, currency, credit and price control skills and were put to use in the management of the post-war economy. The slump of the 1930s necessitated the restructuring of the economy following World War II (the national debt stood at £21 billion by its end) andthe emphasis was placed on economic planning and financial relations.”

Complete and utter BS. The Bank of England’s gold reserves were not sufficient to get the banks out of their self-created predicament. There is no mention of the Treasury Notes whatsoever, because ‘they’ don’t want you to know about that.

The following document from HM Treasury, obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, tells a totally different story.

“The amount and manner of the issue was left to the absolute discretion of the Treasury. This was essentially a War Loan, free of interest, for an unlimited period, and, as such, was a highly profitable expedient from the point of view of the Government.” ‘Banking’, by Dr. Walter Leaf, Home University Library'

This is such an outrageous and arrogant statement. Only a banker could consider this to be an interest-free loan when its purpose was to replace the money they had stolen from the people in the first place. Sure enough, as soon as the War ended the Treasury announced that there would be a gradual reduction in these Treasury Notes or Bradbury Pounds as they had become known. Between 1920 and 1926 the initial £320,600,000 was reduced to £246,902,500. However, even before that as soon as the banks had recovered (thanks to the Bradbury Pounds);

“they were round again at the Treasury door explaining forcibly that the State must, upon no account, issue any more money on this interest free basis; if the war was to be run, it must be run with borrowed money, money upon which interest must be paid, and they were the gentlemen who would see to the proper financing of a good, juicy War Loan at 3.5 percent, interest, and to that last proposition the Treasury yielded. The War was not to be fought with interest-free money, and/or/with conscription of wealth; though it was to be fought with conscription of life.

“Many small businesses were to be closed and their proprietors sent overseas as redundant, and without any compensation for their losses, while Finance, as we shall see, was to be heavily and progressively remunerated.

The Bradbury 10 shilling note (50 pence today or half of one pound - which was itself 20 shillings)

“As each war loan became exhausted the lenders upon the first lower interest War Loans were permitted to transfer into the later higher interest Loans, and usurers' interest upon credit was added to the national burden, so that to-day that burden is insupportable” (ibid)

As the war progressed and more and more people lost their lives in the most hideous manner ,the bankers created a seemingly endless supply of credit out of nothing which they then proceeded to lend to the British nation at ever increasing rates of interest. Estimates from the 1930s put the total figure of ‘magic’ credit at £2,000,000,000 which was lent at a rate of 5% giving a profit of £100,000,000 per year from absolutely nothing at all.

The first War Loan amounted to 350 million, but as there wasn’t that much money in the country, the State received promises of credit from individuals, corporations and banking houses - the very same banking houses who, three months earlier had been begging the Treasury for notes on loan from the Government to save their precious banking system.

Subsequent loans at higher interest rates consolidated the unpaid portions of previous loans (capital and interest) at the new higher rate. By the time of the third War Loan in 1917, which was for a total of £52,000,000, £30,000,000 of that sum was from the consolidation of previous loans and conversions from other previously issued and less attractive interest-rated stocks.

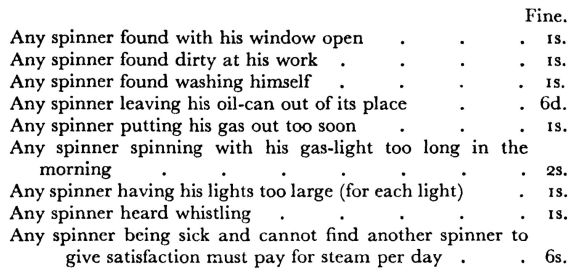

A sick press advertisements issued by the Bank of England in March 1916

Following WWI there seemed to be a stockmarket boom, a period of ‘prosperity’, but it was all an illusion – in fact it was deflation;

“Bankers pressed traders and manufacturers for the repayment of overdrafts, and they obtained the money to do so from the public.” ‘The Annual Register for 1920’

“The big New York bankers had a talk, and they decided that wages must come down. They discussed the matter with the banking mandarins on this side (Britain). Then began a campaign of calling in all credits, of refusing loans to commercial enterprises. The petrol was cut off.” Sunday Chronicle, January 1921

And so it goes on and on. Finance really isn’t my subject, it’s not only boring, but depressing and I don’t pretend to understand the more complex aspects, all I know is that they’re all rotten to their very core. It’s clear that it’s not sufficient to simply point at the Rothschilds as being uniquely responsible for all of this financial devilry. There are many factions involved, not the least of which is The City of London. Competition and general in-fighting may explain many supposedly ‘historical’ incidents that have been whitewashed and used to brainwash us - the great ‘unwashed’.

Wicker figures of Gog and Magog paraded at the annual Lord Mayor’s Show in the City of London. These figures are seen as the mythical protectors of the City's greed

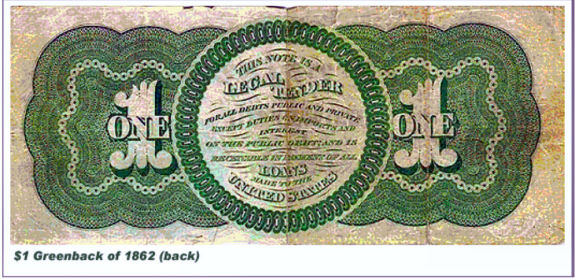

Many people misunderstand the Bradbury Pound incident – those who are aware of it that is. Some see it as a kind of mini-revolution when the government stuck it to the bankers. This isn’t what happened. The bankers got themselves into such a dangerous position that they had to resort to taking a very similar course to that which was taken by Abraham Lincoln in America with the issue of Greenbacks. Lincoln’s action was intended to take the financial cabal down. The Bradbury Pound was intended to save their sorry a*ses. However, it did show the world the way to be free of them, which is exactly why you probably never heard of it before.

Will Scarlet

.

IF YOU ARE SEEING A LINK TO MOBIRISE, OR SOME NONSENSE ABOUT A FREE AI WEBSITE BUILDER, THEN IT IS A FRAUDULENT INSERTION BY THE PROVIDERS OF THE SUPPOSEDLY 'FREE' WEBSITE SOFTWARE USED TO CREATE THIS SITE. THEY ARE USING MY WEBHOSTING PLATFORM FOR THEIR OWN ADVERTISING PURPOSES WITHOUT MY CONSENT. TO REMOVE THESE LINKS I WOULD HAVE TO PAY A YEARLY FEE TO MOBIRISE ON TOP OF MY NORMAL WEBHOSTING EXPENSES - WHICH IS TANTAMOUNT TO BLACKMAIL. I CALCULATE THAT THEY CURRENTLY OWE ME THREE MILLION DOLLARS IN ADVERTISING REVENUE AND WEBSITE RENTAL.